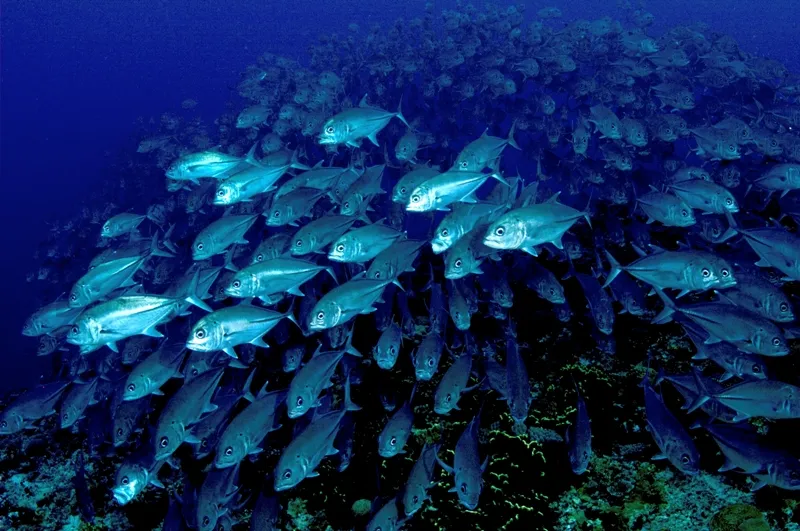

Swimming in Schools May Help Fish Save Energy in Turbulent Waters

A new study suggests schooling fish use up to 79 percent less energy in rough conditions than fish that swim alone

Fish traveling in schools might benefit from a dynamic akin to the one used by the Olympic cyclists currently competing in France, who save energy by grouping together in formations that shelter them from unfavorable headwinds.

In a study published in June in the journal PLOS Biology, scientists propose a new “turbulent sheltering hypothesis” to describe fish movement. It suggests that, similar to cyclists, fish might also save a significant amount of energy when swimming in schools through turbulent waters, as opposed to moving individually.

“The turbulence sheltering hypothesis has not been previously proposed, so this study is the first to both propose and test it,” study lead author Yangfan Zhang, a zoologist at Harvard University, tells Popular Science’s Laura Baisas. “For many years now, there have not been any substantially new ideas on why fish in particular might school and move as a collective group. The turbulence sheltering hypothesis provides a new idea for why fishes might gain an energetic advantage by moving as a school.”

Just as cyclists shield each other from the wind, the scientists thought schools of fish might protect each other from disruptive water currents and ultimately save energy. To test this, they built what the New York Times’ Katrina Miller calls a “water treadmill” for giant danio fish: a tank with a propeller to control the water flow, high-speed cameras to observe their movements and a respirometer to measure their oxygen consumption—in other words, how much energy they were using.

“If you want to measure the oxygen consumption of a human running on a treadmill, then you put a mask on the human’s face,” Zhang says to the New York Times. “But it’s really hard to put a mask on a fish.”

The scientists concluded that when the giant danios swam in groups of eight in turbulent waters, the fish used up to 79 percent less energy than when swimming individually in the same condition. They also noticed that schooling fish used the same amount of energy when they swam in turbulent waters as when they swam in calm waters—they simply grouped together more closely when the conditions got rough. On the other hand, solitary fish used up to 22 percent more energy in turbulent waters by forcefully beating their tails to maintain the same speed as in calm waters.

“We show that being in a school substantially reduces the energetic cost for fish swimming in a turbulent environment, compared to swimming alone,” the authors say in a statement.

This conclusion “is not exactly shocking,” Ty Hedrick, a biologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who was not involved in the study, tells the New York Times. “After all, getting knocked around by turbulence in the water is probably going to require some extra energy.” He was mostly surprised that a school of giant danios uses the same amount of energy in both turbulent waters and calm waters.

Zhang tells Popular Science that fish moving in schools gain “dramatic benefits” in turbulent conditions, which ultimately suggests some fish evolved to live in groups to promote more efficient swimming.

The results could potentially facilitate the creation of more suitable fish habitats, especially when it comes to safeguarding endangered species and thwarting invasive ones, writes Popular Science. Researchers even suggest the study could inspire new energy-saving vehicles or drones, both underwater and in the air.

“There is something really unifying about a principle that happens across biology,” Zhang says to the New York Times. “We can learn a lot from nature.”