Mars Hosts a Giant Reservoir of Water Underground, We Just Can’t Easily Reach It, Study Finds

The water is enough to cover the Martian surface in a mile-deep ocean, but it’s beyond the reach of drills for now, according to researchers

Three billion years ago, Mars was covered with oceans and flowing rivers of water. Today, the Red Planet’s landscape is starkly different, with no liquid surface water—just patches of frozen water ice—and rocky channels and dry lakebeds where rivers and lakes once were.

But miles beneath its surface, Mars might contain a massive reservoir of water trapped within the nooks and crannies of porous, volcanic rock, according to a new study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. If extracted, researchers say it would be enough water to create a planet-wide ocean about a mile deep.

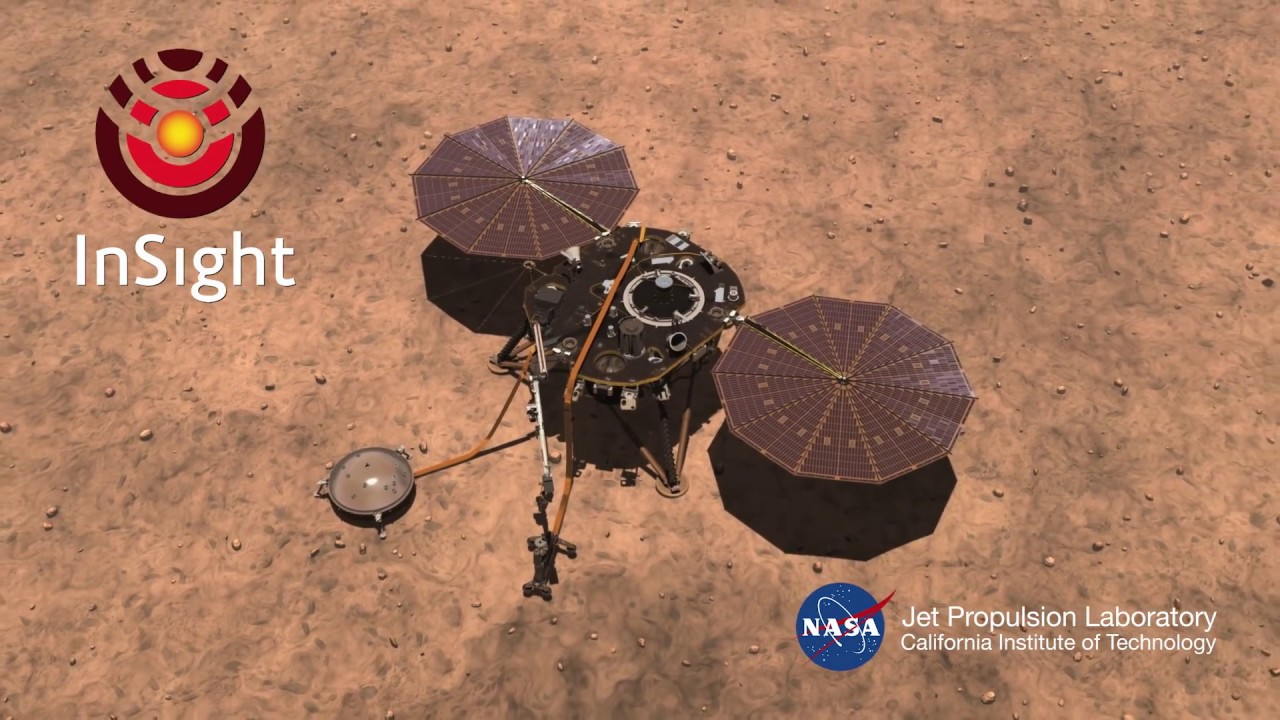

Data from NASA’s InSight lander, a robot designed to study the deep interior of Mars, revealed the underground ocean. Still, the water is not a single, giant reservoir; it’s instead encased within the miniature cracks of the planet’s crust, between about 7 and 13 miles deep. The findings could help researchers piece together what happened to all the water on Mars billions of years ago—and it might be the next place to look for signs of life.

“I don’t see why [the underground reservoir] is not a habitable environment. It’s certainly true on Earth—deep, deep mines host life, the bottom of the ocean hosts life,” study co-author Michael Manga, a geophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley, says in a statement. “We haven’t found any evidence for life on Mars, but at least we have identified a place that should, in principle, be able to sustain life.”

NASA launched the InSight lander on May 5, 2018. After collecting data on Mars’ crust, interior and atmosphere for more than four years, the mission ended in 2022. The spacecraft measured the ‘pulse’ of seismic waves caused by the flow of magma within the planet, meteorites smacking the surface and tremors from Mars quakes.

To find the water, researchers calculated the speed of each Mars quake as it traveled through the planet, reports Ashley Strickland for CNN. The speed depends on which materials lie beneath the surface—where the cracks in rock are, for instance, and whether there is something in those cracks. The team then used a computer model, like the ones that find oil or groundwater on Earth, to interpret the results collected by InSight.

“Oil and gas companies figure out where to drill and extract oil and gas by using exactly the same techniques we use to use seismic waves and what we call rock physics models to interpret that data,” Manga tells Discover magazine’s Paul Smaglik.

It is thought that Mars’ water vanished when the planet lost its magnetic field and atmosphere billions of years ago. But exactly where that water went has remained a mystery. Some is thought to have escaped out into space, as the amount of water now frozen on Mars’ surface pales in comparison to what was once there. But the new findings suggest something else might have happened to the water—perhaps it percolated down into the Martian crust. On Earth, water seeps into small cracks in its brittle crust. Still, because of our planet’s plate tectonics, the water eventually returns to the surface through volcanic eruptions.

If astronauts who travel to Mars want to tap into the groundwater, it will be challenging, writes Asa Stahl for the Planetary Society. The water is trapped in small fissures and holes in the Red Planet’s mid-crust. Drilling so deep would be not easy, even if it were on Earth instead.

“Yes the amount of water down in the crust is potentially vast, but it will be difficult to access or utilise,” Steven Banham, a planetary scientist at Imperial College London who was not involved with the study, tells the Guardian’s Nicola Davis. “It might not make much difference to human exploration, at least initially.”

Still, the discovery is a record of Mars’ geological past.

“These new results demonstrate that liquid water does exist in the Martian subsurface today, not in the form of discrete and isolated lakes, but as liquid water-saturated sediments, or aquifers,” Alberto Fairén, an astrobiologist at Cornell University who was not involved with the study, tells CNN.

“On Earth, the subsurface biosphere is truly vast, containing most of the prokaryotic diversity and biomass on our planet,” he adds. “Some investigations even point to an origin of life on Earth precisely deep in the subsurface. Therefore, the astrobiological implications of finally confirming the existence of liquid water habitats kilometers beneath the surface of Mars are truly exciting.”