How Did Ice Age Humans Kill Huge Animals Like Mammoths? Probably Not by Throwing Spears, Study Finds

New research theorizes that hunters used pikes planted in the ground—with their sharp tips pointing upward—to impale approaching wildlife using the creature’s own weight and momentum

During the Ice Age, early humans lived alongside large animals like mammoths, saber-toothed cats and giant ground sloths. From cut marks on bones, researchers have deduced that early humans sometimes butchered and, presumably, ate the meat of these big creatures.

But one lingering question is how the comparatively small humans could take down such large prey. Did our ancestors simply scavenge wildlife that was already dead? Or did they hunt and kill them? If so, what weapons or techniques did they use to halt such hefty beasts?

Now, new research suggests a possible answer. The Clovis people who lived in North America roughly 13,000 years ago may have planted spears in the ground—with their sharp tips pointing upward—to impale approaching wildlife using the animals’ own weight and momentum. This technique, known as pike hunting, probably would have generated more force—enough to pierce the thick hides of megafauna—than humans throwing or thrusting spears could.

Scientists describe this theory in a new paper published Wednesday in the journal Plos One.

Since 1929, researchers have discovered more than 10,000 Clovis points in North America. Clovis points are sharp, slender, hand-crafted weapons made from jasper, chert, obsidian and other types of stone. They also usually have fluted indentations at the base, which suggests they may have been attached to spear shafts.

The first Clovis points ever discovered were found mixed in with mammoth bones in Clovis, New Mexico. Since then, archaeologists have unearthed more Clovis points near bones, as well as bones with cut marks presumably made by the weapons.

But they’ve long puzzled over how early humans actually used Clovis points. Since other parts of spears were likely made from more delicate materials like wood and pine pitch, those elements probably disintegrated over time. This left unanswered questions about how Clovis points fit into the bigger picture of prehistoric weaponry.

The team of researchers approached these unknowns in two ways. To start, they reviewed historical paintings and depictions from around the world and found several references to pike hunting.

“For millennia … megafauna such as brown bears, lions, jaguars, boars, carabao and warhorses were often slain with a braced piercing weapon, sometimes known as a pike, that uses the animal’s momentum to impale the animal and arrest its movement toward the pike wielder,” they write in the paper.

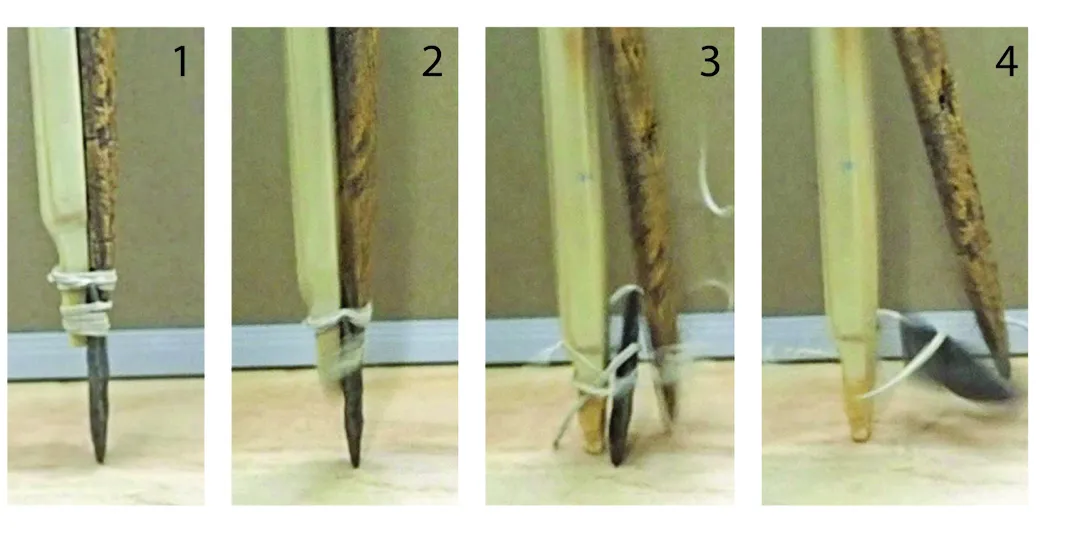

Then, they set up experiments using Clovis spear replicas to simulate how spears with Clovis points might react to the force of a charging animal—including when they reached their breaking point. They built a platform that allowed them to propel a replica spear into an oak plank, meant to represent bone, using varying levels of force. These tests showed that a spear that was thrown or thrust wouldn’t be enough to kill a huge animal. It might penetrate an animal’s skin, but after that, “the impact just dies,” says study co-author Scott Byram, an archaeologist at the University of California, Berkeley, to the Hill’s Saul Elbein.

“People tend to glorify traditional hunting techniques a little bit,” he adds. “They tend to talk about hunting spears as though [hunters] are using their own force to kill the animal—as opposed to getting the animal to kill itself.”

Clovis points took a lot of time and energy to make, and the stones and wood required to produce spears might have been hard to find. Because of that, early humans would have only wanted to use the weapons when they were fairly confident they could actually land an animal, the researchers posit. They wouldn’t have wanted to risk throwing or destroying them. Beyond that, it would have taken a lot of courage to stare down an angry mastodon or cave bear while trying to jab it with a spear.

Together, the evidence points to the use of pike hunting. In the future, the team hopes to conduct even more research to test this hypothesis—such as simulating an attack with a replica mammoth.

“Sometimes in archaeology, the pieces just start fitting together like they seem to now with Clovis technology, and this puts pike hunting front and center with extinct megafauna,” says Byram in a statement. “It opens up a whole new way of looking at how people lived among these incredible animals during much of human history.”

But even with additional experiments, scientists may never know exactly how early humans used Clovis points—unless they can find additional artifacts or evidence to shed light on this mystery.

“The major problem is that archaeologists have never discovered any sort of Clovis wooden spear or dart shaft, much less any hard evidence that spears were actually used in a pike-like fashion,” says Metin Eren, an anthropologist at Kent State University who was not involved with the research, to the Guardian’s Nicola Davis. “We really need to make sure our conclusions don’t outrun our experiments, and, more importantly, the actual archaeological record.”