Museum Settles With Heirs of Jewish Couple Who Sold a 16th-Century Painting as They Fled the Nazis

A Pennsylvania museum will auction the portrait—and split the proceeds with the descendants of Henry and Hertha Bromberg

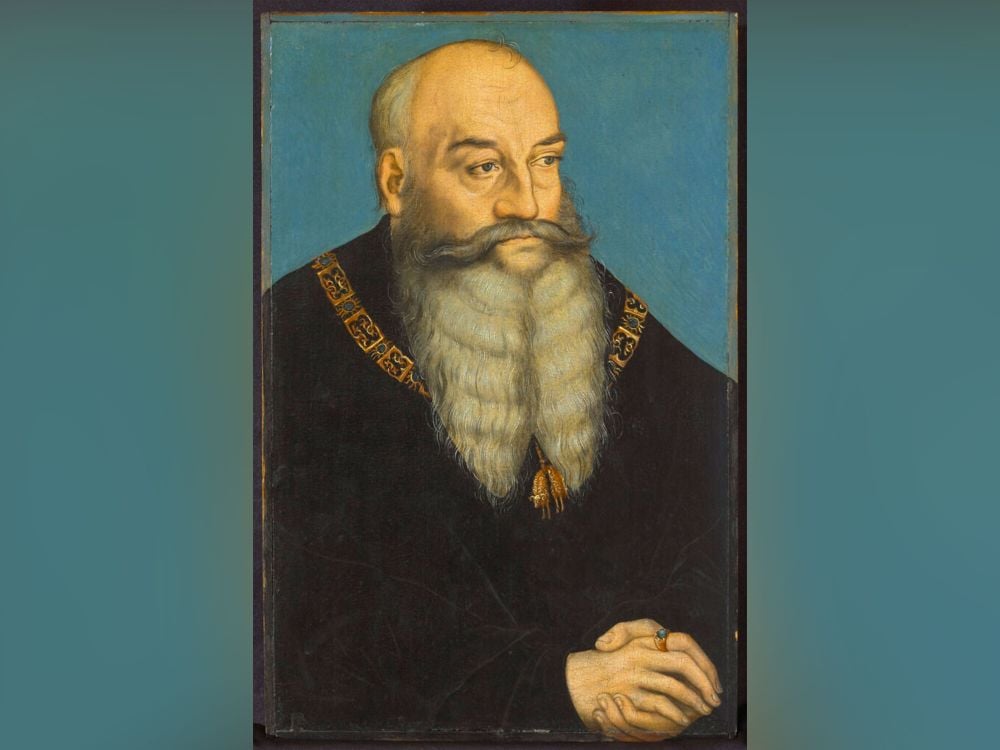

A 16th-century portrait created by Lucas Cranach the Elder and his workshop will be auctioned next year under an agreement between a Pennsylvania museum and the descendants of a Jewish couple who fled Nazi Germany during World War II.

The Allentown Art Museum has had Portrait of George the Bearded, Duke of Saxony in its collection since 1961, when it purchased the work from a New York gallery. The oil painting is thought to have been created around 1534.

In 2022, the museum received a restitution claim for the painting from the descendants of Henry and Hertha Bromberg.

Henry Bromberg, who served as a judge in a magistrate’s court in Hamburg, had inherited the painting from his father. After Adolf Hitler rose to power, the German-Jewish couple sold their collection and left Europe in 1938. The Brombergs arrived in the United States in 1939, living first in New Jersey and later settling in Pennsylvania.

The museum and the descendants disagreed about the timing and location of the sale—did the Brombergs sell the piece before or after leaving Germany? But the parties were still able to reach a compromise, “rather than everybody standing their ground and going to court,” Nicholas M. O’Donnell, the attorney for the museum, tells the Associated Press’ Michael Rubinkam.

The painting will be sold in January 2025, and the proceeds will be shared between the museum and the family in an undisclosed arrangement. The auction house has not released a valuation of the piece.

Max Weintraub, the museum’s president and chief executive officer, says in a statement that museum leaders considered the “ethical dimensions” of the painting’s history.

“This work of art entered the market and eventually found its way to the museum only because Henry Bromberg had to flee persecution from Nazi Germany,” he says. “That moral imperative compelled us to act. We hope that this voluntary act by the museum will inform and encourage similar institutions to reach fair and just solutions.”

In the statement, the descendants—which include the couple’s grandchildren and a close family friend—say they were “pleased” with the “fair and just solution.” They have recovered several other works from the Brombergs’ collection in recent years, though they’re still seeking around 80 pieces.

In 2016, the French government returned a 16th-century portrait attributed to Joos van Cleve or his son to the Brombergs. Two years later, French officials handed over three 16th-century paintings by Joachim Patinir. The descendants have also reached agreements for two other pieces that were in private collections, according to the New York Times’ Graham Bowley.

Before the painting heads to auction early next year, the museum will display it alongside another piece owned by a German-Jewish family before World War II. The installation will illustrate the “different trajectories of the artworks during and after the Nazi period,” per the museum’s statement. The display, which is on view through October 20, will also explain the museum’s decision to return the Cranach portrait to the Bromberg family.

Born in 1472, Cranach was a prolific German Renaissance painter, woodcut artist and muralist. He and his workshop also painted numerous portraits of Martin Luther, the German theologian who sparked the Protestant Reformation.

Christie’s specialists are now conducting a careful analysis of the artwork in order to confirm its attribution.

“This painting has been publicly known for decades, but we’ve taken this opportunity to conduct new research,” says Marc Porter, chairman of Christie’s Americas, in a statement, per the AP. “It’s leading to a tentative conclusion that this was painted by Cranach with assistance from his workshop.”