This Decorated Samurai Sword Found in Rubble Beneath Berlin May Have Been a Diplomatic Gift

The short blade’s hilt was made in Edo Japan, and its journey to a German cellar destroyed during World War II is a mystery

Archaeologists have discovered history buried within history in Berlin. Among the wreckage of a cellar in the city’s oldest square, destroyed during World War II, researchers recently uncovered a rare, finely decorated Japanese sword. The weapon could be up to 500 years old.

The excavations in the historic square, called Molkenmarkt, were conducted in 2022 by researchers from the Berlin State Office for Monument Preservation, according to a statement by the Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Berlin—one of the Berlin State Museums. Archaeologists dug beneath Stralauer Strasse, a street once populated by narrow residential and commercial buildings, and discovered that though the buildings are long gone, their collapsed cellars remain buried in situ.

Researchers’ exploration of these cellars proved fruitful. They found various equestrian artifacts, like bridles, stirrups, bits and harnesses—evidently stored near the end of World War II. And in the rubble of a residential cellar, archaeologists found a heavily corroded sword. Initially, they thought it was a military parade weapon. But as an examination in the restoration workshop of the Museum of Prehistory and Early History revealed, the sword is actually a wakizashi, a short blade traditionally carried by Japanese samurai.

“This discovery is yet another example of the surprising artifacts that are waiting to be unearthed beneath the soil of Berlin,” says archaeologist Matthias Wemhoff, director of the Museum of Prehistory and Early History, in the statement.

Though the sword’s handle is damaged by heat, its wood and some of its wrappings are intact. The handle was swathed in textile and the skin of a stingray—commonly applied to Japanese sword handles for better grip because of its rough texture.

Restoration work revealed several decorative elements on the sword, such as a painted chrysanthemums on the guard plate and a metal carving of Daikoku, a Japanese god of luck, on the handle. Based on these decorations, researchers have dated the sword’s handle to Japan’s Edo period, which took place between 1615 and 1868.

The Edo period is named for a small Japanese town that grew into a metropolis—now called Tokyo—between the 17th and 19th centuries. According to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, the era was a stretch of peace, in which Japanese people pursued higher standards of living than before. The Edo period saw developments in agriculture, cities, education and art, as leaders focused their energies on their own country, isolating Japan from the rest of the world. How an Edo weapon ended up in Germany remains unclear.

“Who could have imagined that such a well-used and ornately decorated weapon would make its way to Berlin at a time when Japan was effectively shut off to the outside world and barely any European travelers visited the country?” Wemhoff says in the statement.

It’s possible the sword was a gift from Japanese ambassadors who visited Germany in 1862 and 1873, during European tours dubbed the Takenouchi Mission and Iwakura Mission, respectively. Through these trips, Japan aimed to build relationships with Western powers. Per the statement, Molkenmarkt is close to the Berliner Schloss, once the palace of Wilhelm I, where the ruler met with both missions. But as Wemhoff notes, the sword’s path from possible diplomatic gift to Molkenmarkt cellar refuse remains a mystery.

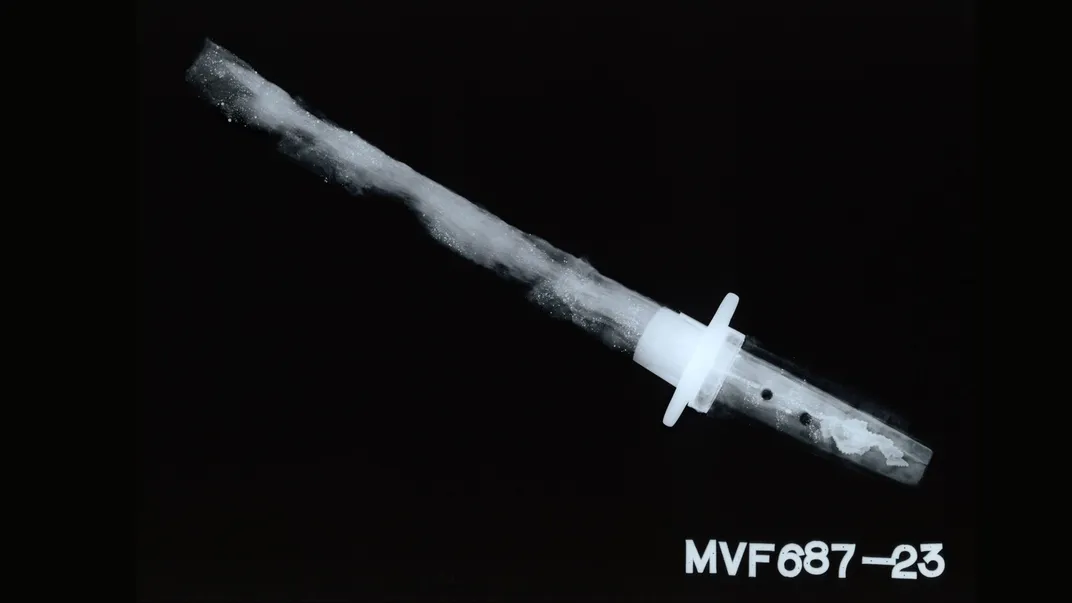

Though restorationists found no blacksmith’s signature on the blade, they discovered through X-ray imaging that the blade was shortened from its original length, suggesting it’s older than initially thought. While the sword’s hilt dates to between the 17th and 19th centuries, the blade was probably forged as far back as the 16th century.

“The discovery of this Japanese short sword in the heart of Berlin has revealed yet again what treasures remain hidden beneath the streets of our metropolis,” writes the museum.