Editor's Note, June 22, 2023: On the afternoon of June 22, the U.S. Coast Guard announced the identification of debris from the tourist submersible Titan, which went missing on Sunday during a dive to the wreck of the Titanic. "The debris is consistent with a catastrophic implosion of the vessel" that would have killed all five crew members on board, including OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush, said Rear Admiral John Mauger during a press conference. Investigations into the cause and timing of the explosion are ongoing. Below, read a 2019 story by magazine correspondent Tony Perrottet, who visited OceanGate headquarters and reported on the company's plans to send tourists to the Titanic.

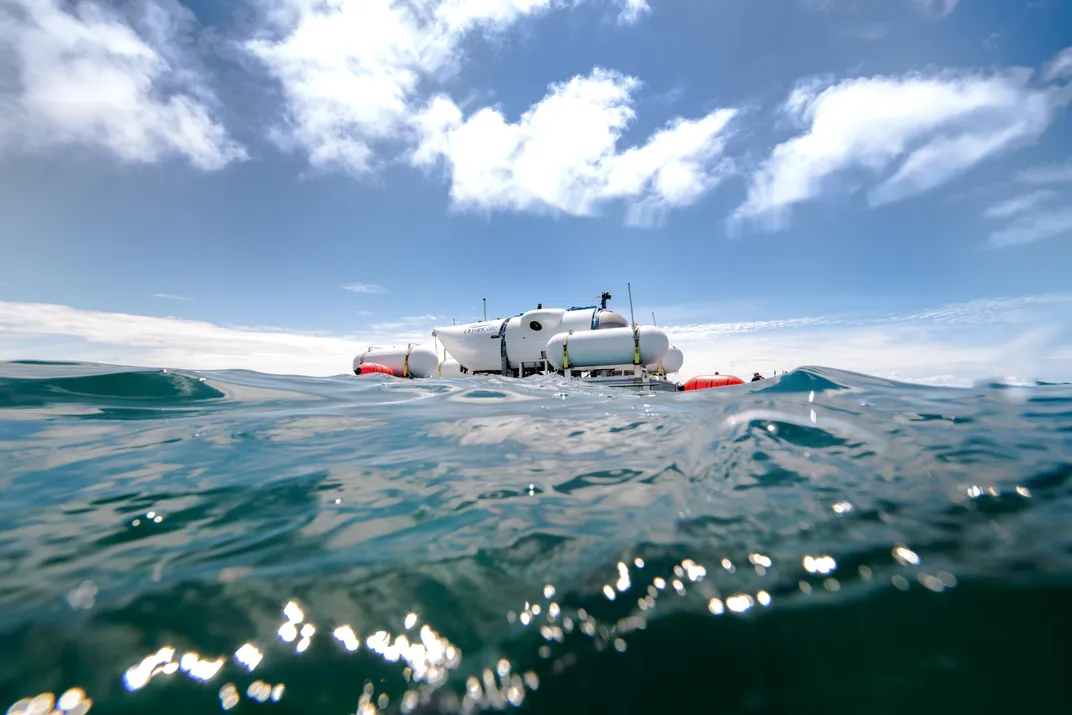

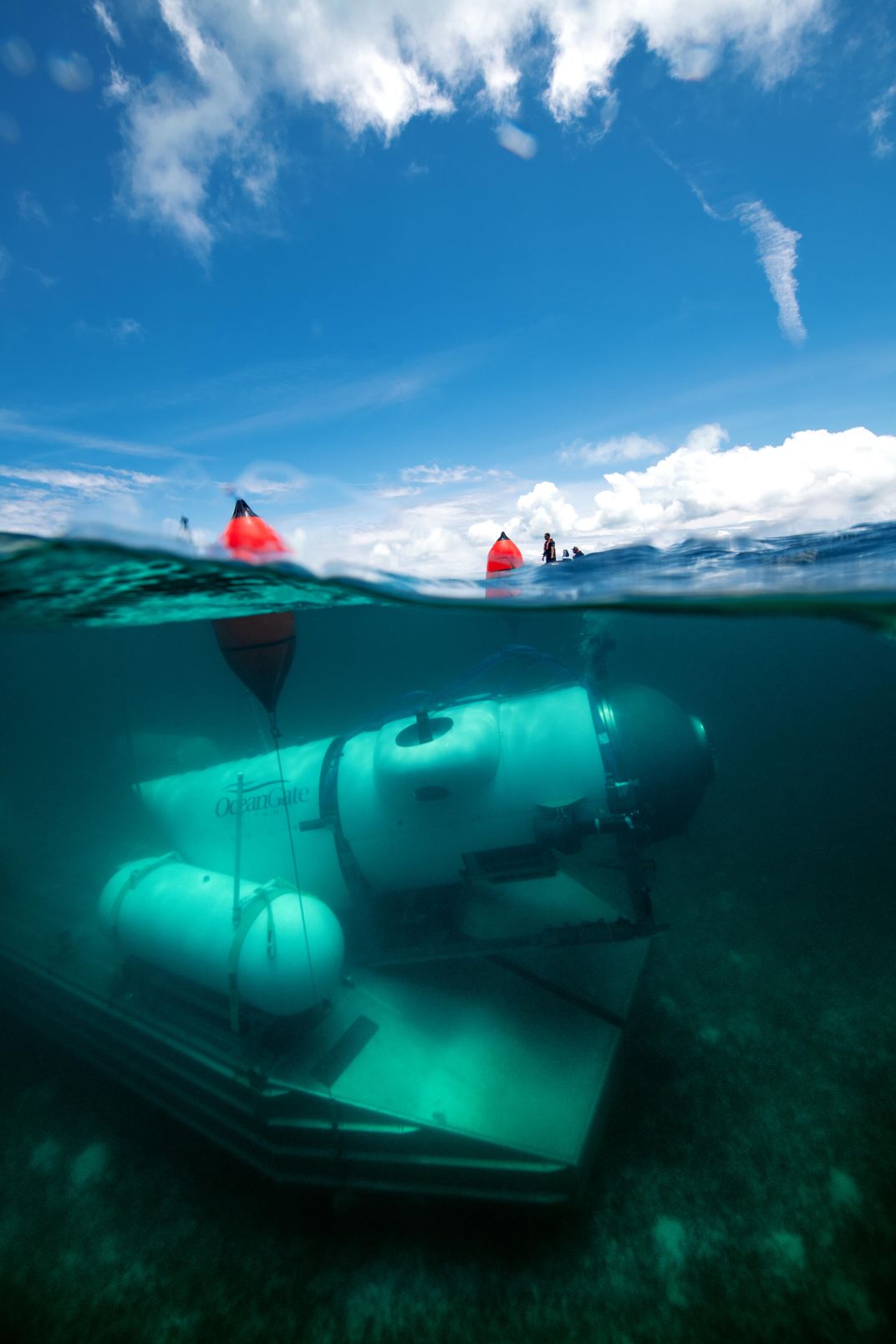

The world looks very different through the eye of the Cyclops. I learned this one freezing morning this past February, after trudging through two feet of snow to get to the marina in Everett, Washington, a small port 45 minutes north of Seattle. On the dock was a cylindrical white pod about the size of a moving van, a five-person submersible whose protruding, semi-spherical window inspired its name, after the monocular monster of myth. A half-dozen men wearing thickly padded khaki jumpsuits and orange helmets gathered on the snow-covered dock ready to send me under the ice-flecked waves of Puget Sound.

The schedule was as rigorously timed as a rocket launch. “Vessel prep” had been completed at dawn, so after a pre-dive briefing, I climbed a ladder to the top hatch of the sub, took off my boots and clambered into the tube, which was sheathed in perforated stainless steel. Inside, the pilot Kenny Hague was checking instruments, including the modified Sony PlayStation controllers used to steer the sub underwater. There were no seats, but with only three of us on the dive (the other was staff member Joel Perry), I could stretch out like a pasha on a black vinyl mat.

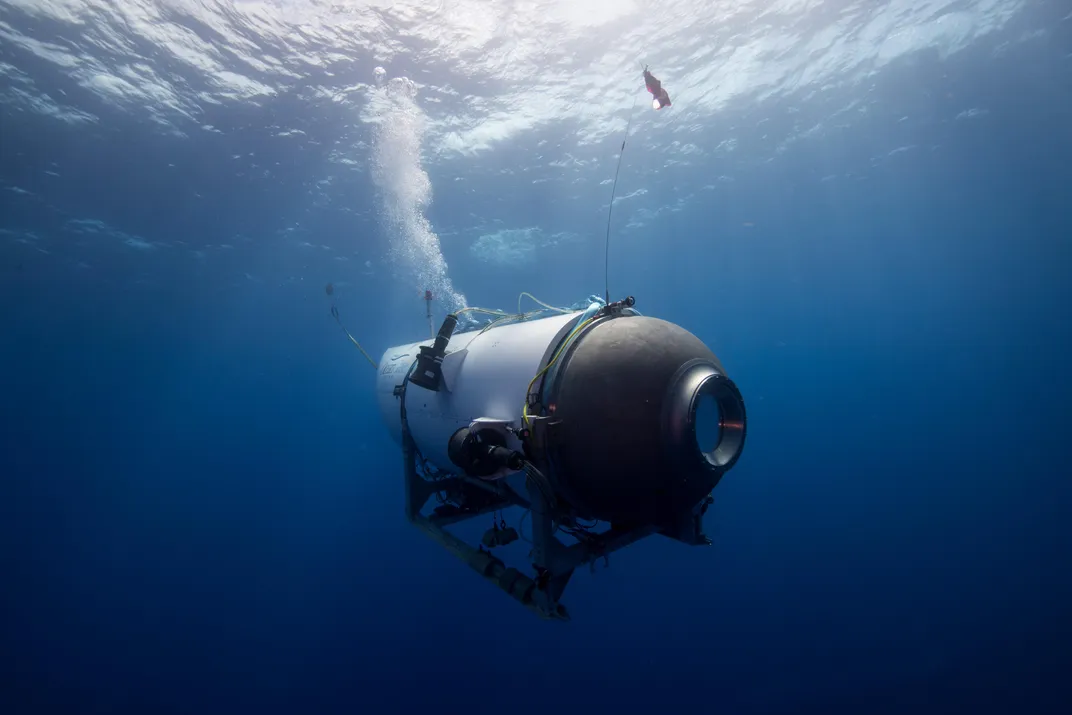

With the submersible still resting on its metal launching platform, one end of the platform slowly rose from the dock and we slid backward into the sea. The milky green waters of Puget Sound rose over the eye of Cyclops 1; the support team blurred and vanished, followed by the leaden sky. Even though visibility was only about 15 feet, thanks to storm runoff, a condition my crew mates dubbed “the milkshake,” it was still magical to be breathing underwater, an unnatural human state that has captured our imagination since antiquity, when Greek legends of Poseidon and mermen abounded. I was reminded, inevitably, of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and Captain Nemo’s near-mystical reverie on the Nautilus over its mastery of the deep: “The sea is everything....It is an immense desert, where man is never lonely, for he feels life stirring on all sides. The sea is only the embodiment of a supernatural and wonderful existence. It is nothing but love and emotion; it is the ‘Living Infinite.’”

This test “dunk,” in the words of my hosts, from a company called OceanGate, was just a taste of what will happen this summer, when OceanGate will begin taking paying customers to visit the fabled wreckage of the Titanic, which lies some two and a half miles beneath the North Atlantic. The experimental submersible for those trips, named Titan, closely resembles its sibling Cyclops 1. But Titan is the first deep-sea submersible constructed from a carbon-fiber composite, which allows the vessel to withstand enormous pressure at great depths while being far cheaper to build and operate than more traditional subs of equal abilities. Though the average depth of the world’s oceans is 2.3 miles, or a little more than 12,000 feet, until Titan came along only a handful of active submersibles were capable of reaching that depth, and they were all owned by the governments of the United States, France, China and Japan. Then, last December, OceanGate made history: Titan became the first privately owned sub with a human aboard to dive that deep and beyond, finally reaching 4,000 meters, or about 13,000 feet—a little deeper than where the Titanic lies.

The feat was the culmination of a dream for Stockton Rush, OceanGate’s maverick CEO and co-founder. “Stockton is a real pioneer,” says Scott Parazynski, a 17-year NASA veteran, the first person to have both flown in space (five times) and summited Mount Everest, and a consultant on the Titan expeditions. “It’s not easy to take a white sheet of paper, come up with a new submersible design, fund it, test it and mature it. It was an incredibly audacious thing to do.”

In his zeal for innovation, Rush stands out even in the elite manned submersible community, which attracts wealthy and eccentric individuals willing to risk their fortunes on wildly uncertain endeavors. Rush wants to do for deep ocean exploration what Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are doing for space travel. By taking well-heeled tourists to the deep—at first, each seat cost $105,129, the inflation-adjusted price of a first-class ticket on the Titanic, though the rate has increased to a cool $125,000—Rush hopes to use private enterprise to spur advances in the long-neglected field of underwater exploratory technology, and reveal some of the secrets of the great blue unknown.

Not that he is given to romantic reveries of the sea. “Sometimes Mother Nature works for you,” Rush said, smiling wryly as he settled into a chair in a wood-paneled parlor in downtown Seattle. “And sometimes Mother Nature is a bitch.” The vagaries of the weather are an ongoing theme for Rush, with deluges, lightning storms and other cataclysms wreaking havoc on Titan’s test schedules. But he was also referring to the difficulties of our meeting, which occurred while Seattle was being pummeled by its snowiest month in half a century, turning roads into rivers of slush and paralyzing transportation. Just reaching a place for us to sit down had the air of an arctic trek in the Edwardian Age, one reason we chose the historic Hotel Sorrento, which was built for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition that put Seattle, then a frontier outpost for gold prospectors and fur-trappers, on the map. Ever since, the city has attracted independent thinkers, inventors and misfits with a spirit symbolized by the iconic Space Needle, built for the 1962 World’s Fair. As we chatted, snow cascaded down outside the hotel window, cocooning us in an eerie silence and creating the sense that we were sitting in a sub on the ocean floor.

With a shock of silver hair and preppy clothes, Rush might be mistaken for a corporate lawyer on casual Friday rather than an ocean adventurer in the mold of a Jacques Cousteau, who was not just a telegenic explorer but also an inventor (of the aqualung, in his case). A conversation with Rush jumps between engineering (“sacrificial weights,” “tensile forces,” and “fairing,” the external shell added to streamline a sub), business (“marketing granularity”) and boyish enthusiasm (Rush has a fondness for “Star Trek” references).

His childhood dream, growing up in a wealthy San Francisco family, was to be an astronaut. His parents assumed he’d grow out of it. “I didn’t,” he says. When Stockton’s father introduced him to Pete Conrad, the commander of Apollo 12 and the first manned Skylab mission (and a personal friend), the astronaut advised the teenage math whiz to get his pilot’s license. So in 1980, at age 18, Rush became one of the youngest commercial pilots in the world, then signed up to fly chartered planes in and out of Saudi Arabia, all while studying aerospace engineering at Princeton. “It was the coolest college summer job,” he says. For his thesis, he designed a high-speed ultralight aircraft; later, he built his own plane, a Glasair III, from a kit. (“You start on Page 1 of the manual, and by the time you get to Page 680, you have a plane!”)

The astronaut dream was dashed when Rush learned that his eyesight wasn’t good enough for him to become a military pilot, in the 1980s still the astronaut fast track. Instead, he moved to Seattle, to work for McDonnell Douglas as a flight-test engineer on F-15 fighter jets, then went to business school. Building on inherited money, he invested in a string of esoteric tech companies (wireless remote-control devices, sonar systems). Still, he dreamed of going to space, perhaps as a passenger on one of the private rockets being developed in the early 2000s by the likes of Richard Branson. In fact, Rush traveled to the Mojave Desert in 2004 to watch the launch of SpaceShipOne, the first commercial craft sent into space. When Branson stood on its wing and declared that a new era of space tourism had arrived, Rush says, he abruptly lost interest. “I had this epiphany that this was not at all what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to go up into space as a tourist. I wanted to be Captain Kirk on the Enterprise. I wanted to explore.”

* * *

As it happened, Rush had been a fanatic scuba diver since he was a teenager, and had ventured to the Red Sea, the Cayman Islands and Tahiti. It dawned on him that Seattle had excellent cold-water diving. “Puget Sound is full of nutrients, so you have sharks and whales and crabs and dolphins and seals and anemones,” he said. “It’s an absolutely incredible place to dive—except that it’s freezing!” He took a cold-water dive class, but was put off by the thick, full-body dry suits and vast amounts of paraphernalia, including multiple air tanks. “I loved what I saw, but I thought, There’s gotta be a better way. And being in a sub, and being nice and cozy, and having a hot chocolate with you, beats the heck out of freezing and going through a two-hour decompression hanging in deep water.”

The obvious next step was to rent a submarine. He was shocked to find that there were fewer than 100 privately owned subs in the world, and only a few were available for charter. He then tried unsuccessfully to buy one. Instead, a London company offered to sell him parts for a mini-sub that could be built using blueprints created by a retired U.S. Navy submarine commander. He completed it in 2006, a 12-foot-long tube in which the pilot lies flat on his stomach and looks out a plexiglass window while manipulating control levers and cruising at a max speed of three knots.

Rush recalls his first dive in road-to-Damascus terms. “While I was building the sub, I was thinking, This is stupid. I should have just bought a robot and explored with that,” he said. “But the moment I went underwater, I was like, Oh—you can’t describe this. When you go in a sub, things sound different, they look different. It’s like you’ve gone to a different planet.” Rush was hooked—and his entrepreneurial instincts were piqued. “I had come across this business anomaly I couldn’t explain: If three-quarters of the planet is water, how come you can’t access it?”

Our ongoing ignorance of the underwater world is something of a historical accident, Rush discovered. After the Moon landing in 1969, there was a tremendous push for ocean exploration in the U.S. “The thought was, that’s the next frontier,” he says. The Navy pumped millions into manned submersibles with names like Alvin, Turtle and Mystic, with research fueled by secret Cold War missions such as the 1974 recovery of a sunken Russian ballistic-missile sub from the Pacific floor. But in the post-Vietnam recession, government funds dried up. In Seattle, military sub researchers went into other areas of defense contracting and maritime side-specialties such as sonar.

Soon after, the private market died too, Rush found, for two reasons that were “understandable but illogical.” First, subs gained a reputation for danger. Working on offshore rigs in harsh locations like the North Sea, saturation divers, who breathe gas mixtures to avoid diving sicknesses, would be taken in subs to work at great depths. It was the world’s most perilous job, with frequent fatalities. (“It wasn’t the sub’s fault,” says Rush.) To save lives, the industries moved toward using underwater robots to perform the same work.

Second, tourist subs, which could once be skippered by anyone with a U.S. Coast Guard captain’s license, were regulated by the Passenger Vessel Safety Act of 1993, which imposed rigorous new manufacturing and inspection requirements and prohibited dives below 150 feet. The law was well-meaning, Rush says, but he believes it needlessly prioritized passenger safety over commercial innovation (a position a less adventurous submariner might find open to debate). “There hasn’t been an injury in the commercial sub industry in over 35 years. It’s obscenely safe, because they have all these regulations. But it also hasn’t innovated or grown—because they have all these regulations.” The U.S. government, meanwhile, has continued to favor space exploration over ocean research: NASA today gets about $10.5 billion annually for exploration, while NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research is allotted less than $50 million—a triumph of “emotion over logic,” Rush says. “Half of the United States is underwater, and we haven’t even mapped it!”

Although Rush can sound as if he’s found a semi-religious calling—he is fond of saying things like “I want to change the way humanity regards the deep ocean”—he is also blunt about his interest in responsibly exploiting America’s natural resources, pointing out that the country’s “exclusive economic zone,” which extends as far as 230 miles from every coast, is vast, thanks to U.S. island possessions. There could be massive oil and gas reserves, rare minerals or diamonds—to say nothing of deep-sea corals and other possible sources of rare chemicals that might, for example, lead to medical breakthroughs. “We don’t know what resources are out there.”

Rush’s first dive in his mini-sub had only been to 30 feet, but he had contracted what he calls “the deep disease.” From 2007, he began descending to ever-lower depths, first testing the sub by lowering it on a rope to see if the hull or windows would crack. “I went to 75 feet. I saw cool stuff. I went 100 feet and saw more cool stuff. And I was like, Wow, what’s it gonna be like at the end of this thing?” He began to fantasize about seeing what’s known as the “deep scattering layer” around 1,600 feet, where marine life is so dense that early sonar scans in the 1940s reported it as a false, ever-shifting seafloor. Experts surmise that in the darkness below that there exist more than a million invertebrate species, most still unknown to marine biologists.

Rush commissioned a marketing study and found demand for “participatory” adventure travel to the deep ocean, and the idea was born to take clients on expeditions to pay for developing new sub technology that would have wider commercial applications—scientific exploration, disaster response, resource speculation. Rush and a business partner (who has since left the company) formed OceanGate in 2009.

When the blizzard eased up, I made the slow pilgrimage with Rush in his SUV north to OceanGate’s headquarters, in Everett, creeping along a highway lined with snow-covered pine trees that loomed like icebergs. The waterfront office seemed crisply corporate except for the telltale scale models of the Titanic and Titan sitting on a shelf. But opening the door to the workshop revealed the company’s hands-on side: an Aladdin’s cave for tech geeks, a jumble of white hulls that looked like shark fins, sculptural engineering parts, oxygen tanks and oddities like a mysterious Perspex sphere whose interior resembled a medieval clock.

There was OceanGate’s first commercial sub, Antipodes, which was painted bright yellow and whose array of dials and meters had a steampunk air. “I wish it were a different color—I can’t stand that song,” Rush said of “Yellow Submarine.” In 2010, he used the five-person Antipodes, which could descend to 1,000 feet, to carry his first paying clients to Catalina Island, off the coast of California; later, he undertook expeditions to explore corals, lionfish populations and an abandoned oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. To refine the tourist experience, he decided to recruit expert guides. “People would ask me about a fish, and I wouldn’t know anything about it,” he recalls. So he brought along marine biologists. “The difference was night and day. Their excitement permeated the sub.”

“Deep disease” now pushed Rush into a new phase: engineering. He abandoned the traditional spherical submersible shape. “It’s the best geometry for pressure, but not for occupation, which is why you don’t have spherical military subs,” he says. Instead, he developed Cyclops 1, a cylinder that fits five people and is strong enough to descend to 1,600 feet. The steel hull was acquired in 2013 from a company in the Azores, who had been using it for 12 years. Its interior was entirely revamped by the OceanGate engineering team and the Applied Physics Laboratory at the University of Washington, who helped integrate new underwater sensors and install the Sony PlayStation controllers, which gave the sub a uniquely intuitive piloting system.

The idea of trips to the Titanic first arose as a marketing ploy. Shipwrecks, Rush realized, were a way to grab public attention. In 2016, OceanGate mounted an expedition with paying passengers in Cyclops 1 to the wreck of the Andrea Doria, an Italian passenger liner that sank off the coast of Nantucket in 1956, killing 46 people. Media interest spiked. “But there’s only one wreck that everyone knows,” Rush says. “If you ask people to name something underwater, it’s going to be sharks, whales, Titanic.”

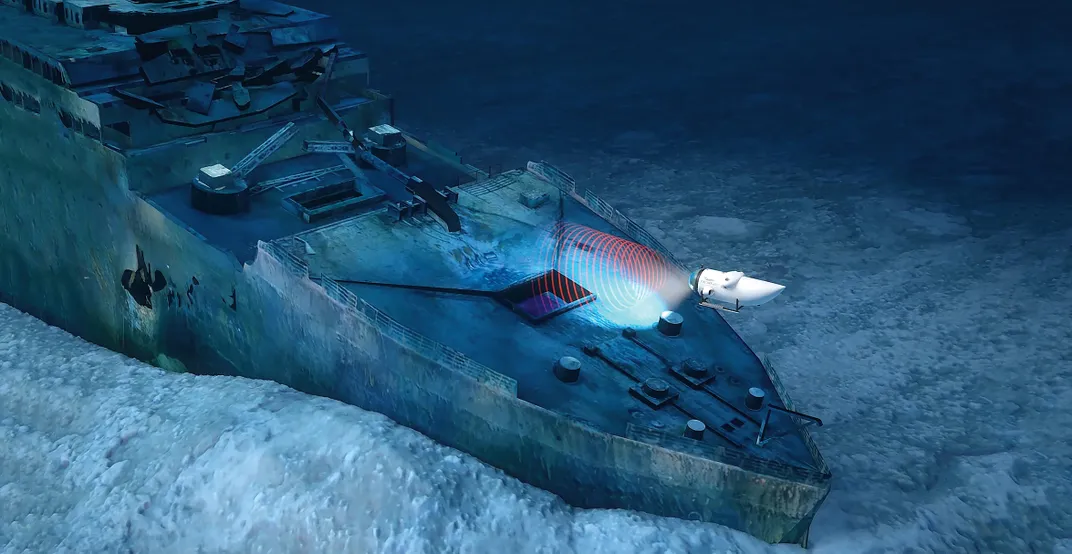

The wreck had been visited by tourists before. More than a decade after the ship was located in 1985, by Robert Ballard, Russia contracted two Mir subs to a company called Deep Ocean Expeditions. (It was also a Mir sub that allowed James Cameron to film the haunting opening scenes of Titanic.) A string of salvage missions funded by private investors has also gathered roughly 5,500 Titanic relics, including plates, unopened Champagne bottles and the window frame of the Verandah Café. Some 250 items are on exhibition in the Luxor Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, along with a piece of the hull recovered from the debris field. (In 2012, the wreck came under the protection of Unesco, which has tried to safeguard the site from looting and further damage.)

Even so, fewer than 200 people have been to the Titanic, and Rush believes there are still original discoveries to be made. The most exciting possibilities lie in exploring the so-called “debris field,” the scattering of the passengers’ personal effects between the two halves of the ship, which broke apart on the surface as it began to sink. OceanGate’s expeditions are also scheduled to conduct sonar, laser scanning and photogrammetric image capture of the entire vessel, in partnership with a company called Virtual Wonders, with an eye toward creating 3-D and virtual reality films, TV shows, video games and exhibition-based immersive experiences.

There was only one catch to Rush’s plan: He still had to prove that Titan could safely get down to the site.

* * *

Ever since 1930, when the American inventor and naturalist William Beebe sank to 800 feet in his “bathysphere,” every deep-sea sub has been made of metal, usually steel or titanium. Rush began to experiment with carbon fiber, a lightweight, extremely strong material long used in the aerospace industry. “We thought, Hey, we can use this stuff to make a really cool sub!”

If it worked, it would be a game changer. The weight of steel and titanium subs makes them expensive to transport on land and requires large ships, outfitted with cranes, to launch at sea. Because of their heft, traditional subs tend to require bulky, syntactic foam flotation blocks to maintain neutral buoyancy, which is crucial for maneuverability. Titan, by contrast, is much cheaper to transport and launch, and without the foam is nimbler in the water. Titan uses the same sleek frame design, control panels, thrusters and life support systems as Cyclops 1, carrying 96 hours of oxygen, but it has a smaller and stronger acrylic window and no top hatch. (Passengers enter through the “eye” itself, as the whole front end of the sub swings open.) Latched onto its 35-foot-long launch platform, it’s transported easily to any location. Most important, Rush believed the carbon fiber body was strong enough to resist crushing pressure down to 13,000 feet.

To test the new sub, Rush chose Great Abaco Island, in the Bahamas. Abaco’s unique advantage is that it sits on the edge of the continental shelf. To reach 13,000-foot-deep waters from Seattle, “I’d have to go 300 miles offshore,” Rush explains. From Abaco, Titan only needs to be towed 12 miles to have 15,000 feet of water to explore. Delays occurred from the start. In April 2018, Titan was in the shipyard just in time for a massive lightning storm that damaged the electrical system, forcing the computers to be replaced. When tests began again in May, an unusual burst of stormy weather postponed the schedule further.

Rush planned to pilot the sub himself, which critics said was an unnecessary risk: Under pressure, the experimental carbon fiber hull might, in the jargon of the sub world, “collapse catastrophically.” So OceanGate developed a new acoustic monitoring system, which can detect “crackling,” or, as Rush puts it, “the sound of micro-buckling way before it fails.” Still, Rush decided to test the hull by lowering the sub to 13,000 feet unmanned. It held.

Last December, the team finally began manned tests, with Rush first dropping 650 feet to the so-called “thermocline,” where tropical water temperature begins to drop precipitously. After successful descents to 3,200, 6,500 and 9,800 feet, Titan was finally ready to plunge to the Titanic’s depth.

The dive was going according to plan until about 10,000 feet, when the descent unexpectedly halted, possibly, Rush says, because the density of the salt water added extra buoyancy to the carbon fiber hull. He now used thrusters to drive Titan deeper, which interfered with the communications system, and he lost contact with the support crew. He recalls the next hour in hallucinogenic terms. “It was like being on the Starship Enterprise,” he says. “There were these particles going by, like stars. Every so often a jellyfish would go whipping by. It was the childhood dream.”

He had been so focused on the task that the achievement of reaching 13,000 feet only hit him when he regained contact with his crew during the ascent. He had chosen to pilot Titan alone in case anything went unexpectedly wrong, he said. But he also wanted to be only the second person to travel solo to at least that depth, the other being James Cameron, who in 2012 took an Australian-built sub into the Mariana Trench, reaching Challenger Deep, the ocean’s deepest point, touching down at close to 36,000 feet. “That’s a nice club to be a part of,” Rush says. Two weeks later, that club welcomed a new member, when a Texas businessman named Victor Vescovo reached 27,000 feet in his own experimental submersible, whose spherical titanium hull is encased in syntactic foam.

* * *

On June 27, OceanGate is scheduled to leave for the first of six trips to the Titanic site.* This summer’s 54 pioneer clients range in age from 28 to 72, and mostly come from the U.S. and Britain, with a few from Australia, Canada and Germany. These 21st-century Astors and Rockefellers are extremophiles, the types of travelers who in the 19th century might have signed up for Amazon explorations and African safaris. Many have traveled to the Antarctic and the North Pole; some have participated in mock dogfights in MIG planes over Russia.

There will be three dives per expedition, and on each descent, three clients will be accompanied by a pilot (drawn from a roster of three, including Rush) and a scientist or a historian specializing in the wreck’s lore. Each dive will involve about 90 minutes of descent, three hours exploring the wreck, and a 90-minute ascent to the surface.

And the future? When the Titanic’s public appeal fades, Rush envisions expeditions to the World War II wrecks in the Coral Sea, to underwater volcanic vents filled with marine life, to deep-sea canyons that no human has ever seen. As for me, the modest dunk in Cyclops 1 gave me an inkling of “deep disease.” As the sub surfaced, every sight and sound seemed strange and unfamiliar. The waterline receded over the sub’s eye to reveal the snow-covered dock and a layer of floating ice; I felt a slight popping in my ears as the hatch opened.

I thought back to a conversation in which Rush painted a portrait of our long-term future that felt, at the time, like science fiction. “We’re going to colonize the ocean long before we colonize space,” he said. In the event that terra firma becomes uninhabitable, undersea settlements could prove more viable “life boats” than interstellar space. “Why leave?” Rush asked. “The ocean is a very protected environment. It’s safe from ozone radiation, nuclear war, hurricanes. The temperatures and currents are very stable.” The idea was undoubtedly far-fetched, and the technology a long way off, but I had to admit that the experience of breathing and moving so freely underwater had captured my imagination. “Every time I go deeper, the experience gets cooler and cooler,” Rush said. “At the very bottom of the ocean, there must be a bunch of octopuses playing chess, wondering why it’s taken us so long to get there.”

*Editor's Note, June 27, 2019: In June 2019, OceanGate postponed its planned Titanic expeditions after failing to secure proper permitting for its contracted research support vessel. The Titanic expeditions are currently being rescheduled for summer 2020.

:focal(3023x1175:3024x1176)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/19/fe193cb7-edf3-4f2b-bfa8-24d53c7699c7/jun2019_f02_submarine_copy-edit.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)