James William Burkhart, better known to his family as “Cowboy,” had an earache. The 2-year-old toddler always seemed to be suffering from an ear-related ailment. On March 9, 1923, his condition worsened so much that his mother, Mollie Burkhart, decided to take him to a physician instead of spending the night at her sister’s house as planned.

Around 3 a.m. the following morning, an explosion shook their town. “It seemed that the night would never stop trembling,” a local recalled. A bomb had reduced the house to rubble, killing Mollie’s sister and her servant. Mollie’s brother-in-law was seriously wounded, and he died of his injuries four days later.

The murders were simply the latest in a string of suspicious deaths to strike Mollie’s family. Another sister had died of a “peculiar wasting illness” in 1918. Three years later, Mollie’s oldest sister was found murdered in a field. The siblings’ mother, Lizzie, died a few months after that, the victim of a suspected poisoning.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/85/65/85658d24-823e-42ba-bda4-e8c115223ecf/mollie_with_sisters_anna_and_minnie.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ab/eb/abeb664c-e122-42a3-abc0-3472c9c33960/newspaperas.jpg)

Mollie had every reason to believe she’d be next on the killer’s (or killers’) list. She now held her family’s oil headrights, an inheritance worth an inflation-adjusted hundreds of thousands of dollars annually. “It was just fate” that she and her children had escaped the explosion, Mollie’s granddaughter, Margie Burkhart, later told journalist David Grann.

A century after the bombing, Killers of the Flower Moon, the newest film from legendary director Martin Scorsese, is bringing renewed attention to the Reign of Terror, a spate of murders that devastated both Mollie’s family and the broader Osage Nation in the early 20th century. Following the discovery of oil on their lands in and around Pawhuska, Oklahoma, in the late 1800s, the Osage became the richest people in the world per capita, amassing great wealth that white settlers quickly plotted to claim as their own. In the span of just a few years, at least 24 Osage Indians, and perhaps even as many as 150, died under violent or suspicious circumstances.

“It was a really unsettling time in our history because of what was being done to us,” says Tara Damron, a member of the Osage Nation and a project director at the Oklahoma Historical Society. “The irony is that it was Osage money and Osage land, and it was never [the white conspirators’] to begin with.”

Based on Grann’s 2017 book of the same name, Killers of the Flower Moon, which arrives in theaters Friday, stars Blackfeet actor Lily Gladstone as Mollie and Leonardo DiCaprio as Mollie’s husband Ernest Burkhart. Robert De Niro and Jesse Plemons round out the cast as Ernest’s uncle, a cattle rancher-turned-political boss named William Hale, and federal agent Tom White, respectively. Though an examination of the case by the Bureau of Investigation, the predecessor to the FBI, suggested that Hale was the mastermind behind the murders, Grann’s research and Osage oral histories point to a more sweeping conspiracy involving the Osages’ white neighbors and their supposed friends.

“I thought I was writing a book about this singular evil figure who had been apprehended by the FBI,” says Grann. “Instead, I began to realize that this was less a story about who did it and who didn’t do it. It was really about a culture of killing and a culture of complicity, … [with] many of these murders carried out by individuals who were profiting from this very corrupt system of targeting the Osage, often marrying into their families and then plotting to kill them to steal their oil money and inheritance.”

Killers of the Flower Moon on the page versus the silver screen

A longtime staff writer at the New Yorker, Grann started researching the murders in 2012, when he visited the Osage Nation Museum in Oklahoma after learning about the case from a historian. During his visit, he noticed a panoramic photograph of Osages standing alongside white settlers in 1924. But a section of the image was missing, seemingly intentionally removed. When Grann asked the museum director about it, she replied, “The devil was standing right there.” She then showed him the missing panel, which featured Hale “staring coldly at the camera,” according to Grann’s book.

“I was really haunted by that photograph, because I kept thinking that the Osage had removed enough to forget what had happened,” Grann says. “But there were so many people, including myself, who had never been taught this [history]. We had never learned it. We had effectively excised it from our conscience.”

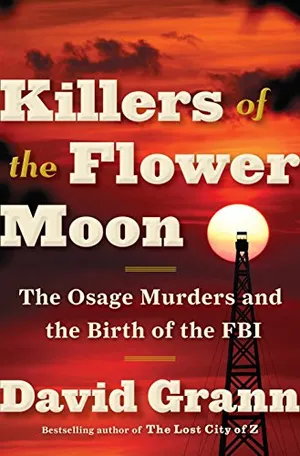

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI

The 2017 book that inspired the new movie

Determined to confront the injustices experienced by the Osage, Grann embarked on a five-year research project, diving into the archives and tracking down descendants of both the murderers and their victims. As he interviewed Osage elders, he realized that the number of suspicious deaths in the Osage Nation during the Reign of Terror far exceeded the estimated death toll of 24. Many of these deaths were never properly investigated.

Grann’s book is split into three sections. The first focuses on Mollie and her family, while the second is dedicated to the FBI investigation led by White. The third addresses major gaps in the FBI’s findings, revealing the extent of the conspiracy against the Osages. “You have morticians covering bullet wounds, doctors who were administering poison, businessmen and lawmen who were on the take, and many others who remained complicit in their silence,” Grann says.

Initially, Scorsese’s film centered on the federal investigation, with DiCaprio playing White. After the director visited the Osage Nation and met with Osages who encouraged him to rethink this approach, he shifted focus, placing Mollie and Ernest’s relationship at the heart of the narrative. The production team sought extensive input from the Osage, working with them to ensure the film accurately portrayed their culture. The movie was filmed on location in Oklahoma, with Osages both in front of the camera and behind it, creating the costumes, sets and other key elements of the 1920s environment. DiCaprio, Gladstone and De Niro even learned the Osage language.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0f/76/0f7611a5-e64b-46d9-8a53-d4bea3f5b80c/killers_of_the_flower_moon_photo_0105.jpg)

“We made sure as to the accuracy of the places of where it happened, and to be around our people, and to get firsthand knowledge of who we are, how we do things, and how generous we are, and how trusting we are,” Chad Renfro, who served as the Osage’s ambassador to the filmmakers, tells Smithsonian magazine’s Sandra Hale Schulman.

Kevin Gover, Under Secretary for museums and culture at the Smithsonian Institution and the former director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, says the book and movie are effective because “the creators took the time to work with the people themselves. They weren’t there to tell a white person’s version of the story, but rather to tell the Native American version of the story, the authentic version of the story.” A citizen of the Pawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, Gover hopes Hollywood follows the example set by Killers of the Flower Moon in future retellings of Native history.

How oil changed the Osages’ lives

The origins of the Reign of Terror lie in the 19th century, when white settlers and the federal government forced the Osage out of their ancestral lands in what is now Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma and Kansas. In search of a new home, the Osage purchased 1.5 million acres in northeast Oklahoma in 1872, establishing what was then the Osage Reservation and is now Osage County.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/94/ff/94ff16b9-ff98-49cf-bb0c-89c739956d71/indian_land_for_sale.jpeg)

The fact that the Osage owned their reservation afforded them a measure of protection from the government’s increasingly brazen land grabs. Under the 1887 Dawes Act, reservations could be divided into allotments, or 160-acre parcels of land granted to individual Native Americans for farming. Intended to encourage assimilation, the policy emphasized private ownership over the traditional communal lifestyle of many Native peoples. Any “surplus” land outside of the allotments was opened up to white settlers.

The Osage used the government’s intense desire for allotment to negotiate favorable terms, much stronger than those accepted by other Native nations. An agreement made with federal authorities in 1906 increased the size of the Osage’s individual allotments and, most crucially, ensured the tribe retained communal ownership of the minerals beneath its lands.

“Instead of allowing chance to decide which persons would get rich from oil and gas royalties, the tribespeople would share equally in the wealth from the reservation’s underground resources,” wrote Terry P. Wilson in The Osage. Each of the tribe’s 2,229 members received a headright, or share in oil money that could be inherited but not sold. One individual could inherit multiple headrights (as Mollie did following the deaths of her family members); alternatively, headrights could be divided as they were passed down across generations, leaving multiple heirs with a portion of a single share. Non-Native people were eligible to inherit headrights, so fortune-seeking white settlers could obtain shares in the tribe’s oil rights by marrying into an Osage family or otherwise maneuvering their way onto an Osage’s list of heirs.

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, the reservation’s resource-rich lands generated more wealth than all of the American gold rushes combined in just two decades. White prospectors leased oil fields from the tribe, making the Osage so rich that one California newspaper deemed them the “most to-be-envied” people in the country. A 1920 analysis estimated that each Osage received around $10,000—roughly $153,000 today—annually.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/65/c1/65c199af-b9ad-4662-86ed-e5ee6ec72481/drilling.jpg)

“[Osages] traveled in Cadillacs and Lincolns, and they had flamingos and peacocks,” said Meg Standing Bear Jennings, sister of the current Osage chief, in the documentary “America’s Hidden Stories: The Osage Murders.” Some even purchased private planes. White observers’ jealousy over the tribe’s lavish lifestyle was readily apparent in newspaper coverage, with reporters describing the Osages as “the laziest people on Earth” and “a primitive type of man” who were “slow to civilize.”

As the Osage’s wealth grew, the federal government took steps to impose restrictions on the tribe’s financial autonomy. In 1921, Congress passed a measure requiring Osages to undergo a competency test to manage their own estates. Those deemed incompetent by the Bureau of Indian Affairs were assigned a white guardian who oversaw “all of their spending, down to the toothpaste they purchased at the corner store,” writes Grann.

The system was corrupt from the start, with guardianship appointments handed out to powerful white citizens and the label of “incompetent” most often applied to those with full Osage ancestry rather than those of mixed heritage. Many guardians abused their positions, selling their wards goods at highly inflated prices or stealing money from them outright.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9b/fa/9bfa072f-755c-48a3-8db0-236591117cf0/osage_with_car_copy.jpg)

“I don’t think a lot of people understand how much tremendous government regulation American Indians were under, because we weren’t even considered citizens of the United States until 1924,” says Damron. “American Indians were also … the only group of people that actually had to prove their blood quantum,” or percentage of Native heritage.

The Osage murders

Like many Osages, Mollie; her mother, Lizzie; and her oldest sister, Anna Brown, all had white guardians. Scott Mathis, owner of the Big Hill Trading Company, oversaw Anna and Lizzie’s finances, while Ernest, who married Mollie in 1917, managed her estate.

In 1921, Anna was newly divorced. She spent much of her time drinking bootleg whiskey and partying with white men, including Ernest’s younger brother, Bryan Burkhart. On May 21, she showed up drunk to a luncheon at Mollie’s house, arguing with the other guests while swigging whiskey out of a flask. That night, Anna disappeared, supposedly heading back out on the town after Bryan dropped her off at home. When she failed to resurface after three days, Mollie mobilized the family to look for her, to no avail.

On May 28, a teenage boy found Anna’s body in a ravine. Based on the level of decomposition, she’d been dead for several days, killed by a bullet wound. That same day, in another part of Osage County, an oil worker discovered the badly decomposed body of Charles Whitehorn, an Osage man who’d vanished a week before Anna. Whitehorn had two bullet holes in his forehead, seemingly from a .32-caliber pistol—the same type of weapon believed to be used in Anna’s murder.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/66/b5/66b5ebaf-2687-449f-9d62-3a037a253a3e/screenshot_2023-10-17_at_94026_am.png)

The Pawhuska Daily Capital announced the grim news with a headline guaranteed to spark speculation: “Two Separate Murder Cases Are Unearthed Almost at Same Time.” Yet inquiries into the deaths failed to offer any concrete explanations, simply concluding that Whitehorn and Anna had died at “the hands of parties unknown.” Shortly after the inquiry into Anna’s murder was closed in July 1921, Lizzie died after a long illness.

The May murders were the most compelling indicators that a conspiracy was afoot in Osage County. But they weren’t the only unexplained or violent deaths to take place in the community in the early 1920s. “A lot of Osage just start dying” despite being young and seemingly healthy, says Damron. White individuals who tried to intervene on the Osage’s behalf also fell victim to the conspirators: In 1922, Bernard McBride, an oilman who’d once been married to a Creek Indian woman, was stabbed and beaten to death during a visit to Washington, D.C., where he planned to ask federal authorities to investigate the Osage murders. Lawyer W.W. Vaughan was thrown from a train shortly after he came into possession of incriminating documents related to the case in 1923.

Though Osages like Mollie and her family sought justice for their loved ones by hiring private detectives and issuing rewards for information, “they were often ignored,” says Grann. “Sometimes, [their] testimony wasn’t even taken because of extreme prejudice at the time, and because many of the lawmen and authorities … were actually complicit in this wicked system” of targeting the Osage. To protect themselves, Osages strung lights around their houses to illuminate them at night, carried guns and even moved out of state.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/28/38/28386c43-50ec-45ad-8508-f6930d7e96ad/metadc1701078_xl_2012201ovz0013441.jpg)

In February 1923, hunters discovered the body of Henry Roan, a 40-year-old Osage man who’d briefly been married to Mollie in their youth. Shot in the head with a .45-caliber revolver, he’d been dead for several days.

Like Mollie, Roan had spent much of his childhood at a boarding school, where he and other Native students were forced to forget their traditional ways and assimilate into white culture. “When I try to describe my great-grandfather’s short existence, … half of it was spent being in the turmoil of that boarding school experience,” Jim Gray, a former chief of the Osage Nation and a descendant of Roan, tells Chris Klimek, host of Smithsonian’s “There’s More to That” podcast. “The last half was trying to find a place that he felt at peace in, and he never did find it.”

Roan considered Ernest’s uncle William Hale one of his closest friends, and his $25,000 life insurance policy listed the white man as its beneficiary.

The deaths cast a “dark cloak of mystery and dread” over the Osage, according to a reporter at the time. But Mollie and her remaining family members continued seeking answers, even as Mollie’s health deteriorated and threats of retaliation mounted. Shortly after her sister Rita Smith and brother-in-law Bill Smith moved into a new house, Bill told a friend he didn’t “expect to live very long”—a prediction that proved prescient. On March 10, 1923, the bomb that Mollie providentially avoided destroyed the couple’s home, killing Rita and their white servant, Nettie Brookshire, and fatally injuring Bill. Public outrage over the brazen murders, coupled with a petition to the government by the Osage Tribal Council, finally convinced federal authorities to open an investigation into the Reign of Terror.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/62/a6/62a61419-48a0-4232-bc6e-381bbc052827/gettyimages-1496135583.jpg)

Investigating the Osage Reign of Terror

Speaking with Vulture, Gladstone, the actor who plays Mollie, emphasizes the Osages’ role in launching the federal investigation, which they pooled $20,000 to fund themselves. “It’s not a white-savior story,” she says. “It’s the Osage saying, ‘Do something. Here’s money. Come help us.’” Despite the tribe’s eagerness to aid the detectives, the case stalled, only gaining ground in 1925 when J. Edgar Hoover asked Tom White, a former Texas Ranger, to take over. White and his colleagues reinterviewed witnesses, recruited undercover agents and took a methodical approach to their detective work. Before long, they realized that much of the evidence pointed to two figures with close ties to the victims: William Hale and Ernest Burkhart.

Born in Texas in 1874, Hale settled in Osage territory around the turn of the 20th century. A cattle rancher by trade, he “was larger than life,” Gray tells Smithsonian. “He spoke Osage. He ingratiated himself into the community. They say the devil doesn’t show up with horns and a tail. He shows up smiling, charismatic, very approachable.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/98/5a/985a47f2-222e-47b5-a700-bed645631377/osage_murders_9.jpeg)

Though Hale presented himself as a friend to and advocate for the Osage, this attitude was a facade. Already wealthy from various business ventures, his greed led him to conspire to kill multiple Osages in hopes of claiming their oil headrights. Mollie’s family was at the center of these plans, with Hale using his nephew’s marriage to his own advantage.

White’s investigation revealed the extent of Hale’s influence, showing how he’d paid off or intimidated authorities and criminals alike. While Grann views Hale as the “embodiment of evil,” he says Ernest “seems to have a conscience, and yet slowly and increasingly becomes complicit in these crimes. … His importance is in some ways his ordinariness. He wasn’t a mastermind, but he went along [with the plan].”

In January 1926, authorities arrested Hale and Ernest for the murders of Bill, Rita and Brookshire. Hale seemed unperturbed by his arrest, certain his connections would save him from conviction. Ernest initially maintained his innocence but broke under questioning, implicating his uncle in the deaths of not only the Smiths but also Roan. He named an undercover informant who’d supposedly been working on the bureau’s behalf as Anna’s killer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2a/97/2a979fc3-cc45-48af-b8d5-b4e2a239616f/james_a_stout_william_k_hale_john_ransey_and_ja_clouse_1926webp.png)

The trials of Hale, Ernest and co-conspirator John Ramsey captivated the nation, with Americans eagerly following courtroom reports in the pages of the New York Times and other major newspapers. In a dramatic turnabout, Ernest recanted on the stand before changing his mind and confessing to his role in the killings. In June, he was sentenced to life in prison and hard labor.

It took until 1929 for a jury to find Hale and Ramsey guilty. As Grann writes, “It seemed impossible to find 12 white men who would convict one of their own for murdering American Indians.” Ultimately, both Hale and Ramsay received life sentences. Neither Hale nor Ernest served their full sentences: The former was paroled in 1947 at age 72, while the latter was paroled in 1937 but sent back to prison after committing a robbery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/dc/59/dc5993c0-884e-43a9-8d6e-865e2b46d782/ernest-burkhart.jpg)

At the time of Ernest’s arrest, Mollie was seriously ill—the result, authorities suspected, of slow poisoning by her doctors, the brothers James and David Shoun. But she “immediately regained her health” upon being removed from the Shouns’ care, an agent later wrote in a report. Informed of her husband’s role in the deaths of her family members, Mollie reportedly said Ernest was “a good man, a kind man [who] wouldn’t have done anything like that.”

Ultimately, though, the evidence against Ernest proved overwhelming. Mollie divorced him, and “whenever her husband’s name was mentioned,” Grann writes, “she recoiled in horror.” Her son, Cowboy, had to live with the knowledge that his father had tried to kill him, with only luck and an earache saving him from dying in the explosion at the Smiths’ house. As Renfro, a consulting producer on the film, tells Time, the deep betrayal experienced by Mollie and her children mirrored the Osage’s broader betrayal by “governmental agencies and people who came in and took advantage of us” over multiple centuries.

By placing the Osage, rather than the FBI investigation, at the heart of Killers of the Flower Moon, “Scorsese and his team have restored trust, and we know that trust will not be betrayed,” said Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear during a press conference.

The lasting consequences of the Reign of Terror

Hoover and the bureau claimed they’d ended the Reign of Terror by arresting Hale and his accomplices. “The moment a couple of the killers were caught, Hoover wanted to close up shop, declare victory, and move on and use the case to burnish the reputation of the FBI,” says Grann. In truth, however, the conspiracy had a far greater reach than authorities acknowledged. Multiple murders remained unsolved, among them those of Whitehorn, McBride and Vaughan. Many more victims of the Reign of Terror had yet to be identified as such.

Decades later, when Grann interviewed Osage elders, they told him about suspicious deaths in their families that had never been investigated. A booklet found in the National Archives further pointed to the sheer number of Osages killed or otherwise abused by their white guardians.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/85/8e/858e5f63-d68f-44c4-9153-6f5ca8357ac9/screenshot-2023-10-17-at-101647-am.jpg)

“I noticed there was a guardian who had five Osages whose fortunes they had managed, and I noticed the word ‘dead’ next to the first name,” the second name and so on, Grann recalls. Another list of a dozen Osages showed a 50 percent mortality rate, far surpassing any natural death rate.

“I could sometimes find little traces or whispers … indicating complaints … about oil money being stolen, or allegations that someone had been poisoned,” Grann says. “And I realized that this little booklet contained the hints to the systematic murder campaign.”

Damron, too, has found evidence of Osages being targeted for their headrights: In the documentary, which aired in the spring, she showed the filmmaker records related to his own great-grandmother Odell Revard, who died in 1928, reportedly by suicide after her stepmother handed her a gun. The papers showed that Revard had complained about her stepmother, who also served as her guardian, stealing her money. After Revard’s death, the stepmother filed a claim for her estate for $45,000—another instance of suspicious circumstances with no proof of foul play.

This lack of closure is a common theme among Osages investigating their ancestors’ stories. “There was no way to bring clarity, [because] the perpetrators, in many of the cases, had erased not only the victims’ lives, but also their history,” Grann says. “That was the most daunting challenge [of my research] and, sadly, one I could not overcome.”

WAHZHAZHE ALWAYS | We live our culture and embrace our future. Our language, culture, and traditions define our Nation. We work to preserve and practice these things so our culture continues to grow. #wahzhazhealways pic.twitter.com/GxUm3AZc0u

— Osage Nation (@Osagenation) May 19, 2023

Damron points out that the “exploitation and infiltration” of the Osage didn’t stop with Hale. The U.S. government, which managed the guardianship system through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, failed to protect the Osage during the Reign of Terror. Today, it remains the trustee of the nation’s mineral estate. Approximately 26 percent of the Osage’s headrights are owned by non-Osage individuals and institutions. Though the Osage have sought federal legislation allowing these entities to sell or gift these headrights back to the nation, their efforts have yet to bear fruit.

Killers of the Flower Moon will undoubtedly bring new attention to the Reign of Terror. But the Smithsonian’s Gover wonders whether this publicity will have a lasting effect. “I suspect … most people will see [the movie] and go, ‘Geez, that’s really terrible. What’s for dinner?’” He emphasizes the importance of “the aftermath of the movie, the tribes talking about it, scholars talking about it, hopefully even political leaders and the actors themselves talking about it, saying, ‘This is what people are capable of, and we must see that it never happens again.’”

In a statement marking the film’s release, the Osage declared, “We are not relics. The Osage Nation is thriving on our reservation in northeast Oklahoma—a people of strength, hope and passion, honoring the stories of the past and building the world of the future.”

Damron echoes this sentiment, saying, “We as a people survived that horrible assault on our ancestors. … It’s still something that’s a part of us, but it doesn’t define us.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ae/c7/aec781c2-fe44-4eae-94e3-ba086b24011e/killers_of_the_flower_moon_feature_photo_0102.jpg)

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/37/f0/37f06ba1-b142-48c0-a763-270fd72486a3/killers.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)