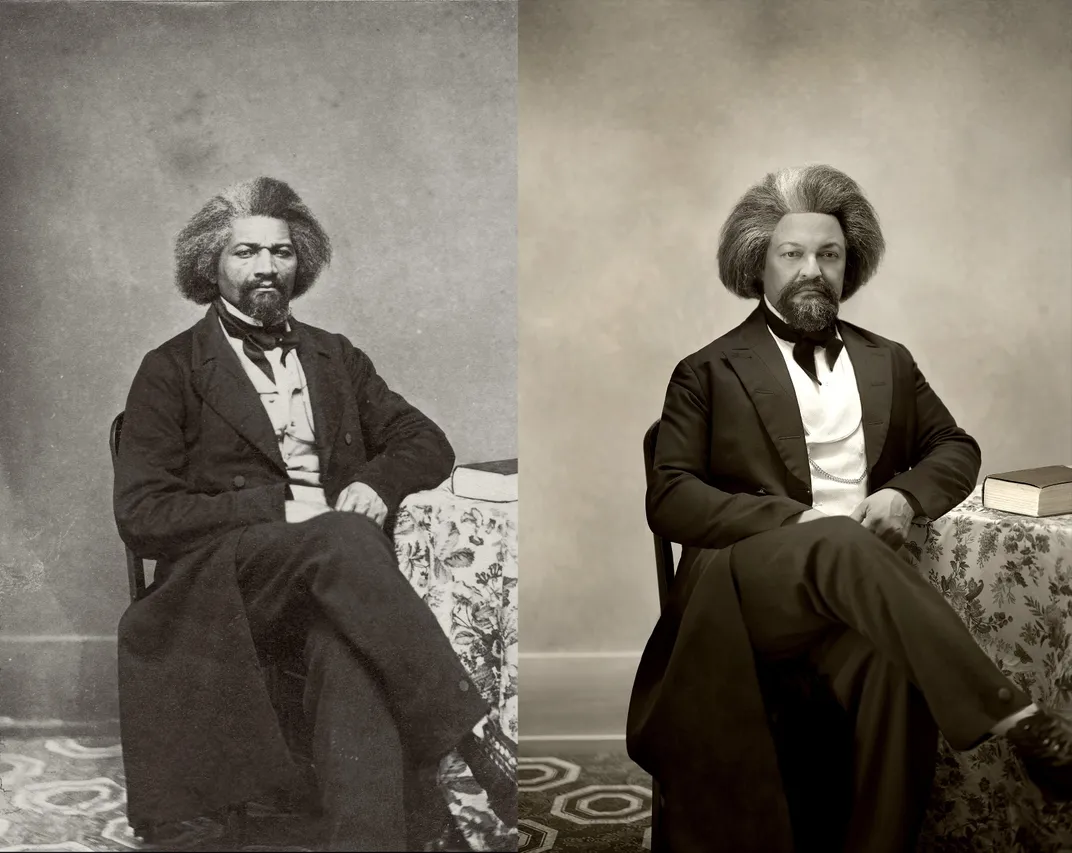

For as long as he can remember, Kenneth Morris has been told he looks just like his great-great-great-grandfather, Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave, author, orator and social reformer. Morris has carried on his ancestor’s mission by fighting racial inequity and human trafficking through the Frederick Douglass Family Initiatives, which he co-founded. But when he actually dressed up as Douglass—complete with a magnificent gray-streaked wig—a strange feeling came over him. “I looked at myself in the mirror, and it was like I was Frederick Douglass. It just transformed me.”

Morris was taking part in an extraordinary history experiment by a British photographer named Drew Gardner. About 15 years ago, Gardner started tracking down descendants of famous Europeans—Napoleon, Charles Dickens, Oliver Cromwell—and asking if they would pose as their famous forebears in portraits he was recreating. Then he looked across the Atlantic. “For all its travails, America is the most brilliant idea,” says the Englishman. He especially wanted to challenge the idea that history is “white and male.”

He found Elizabeth Jenkins-Sahlin through an essay she’d written at age 13 about the suffragist leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton, her mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s mother. Jenkins-Sahlin spent her teen years speaking and writing about Cady Stanton; in 1998, she appeared at a 150th anniversary celebration for the Seneca Falls Convention. “I felt like a clear role had been given to me at a young age,” she says. By age 34, though, when Gardner contacted her, she was carving out her own identity, and was initially reluctant to take part in his project. Yet sitting for this recreated photograph of a young Cady Stanton, wearing curls and a bonnet, helped her get inside the eminent progressive’s psyche in a whole new way. “I was really trying to imagine the pressure she felt. This was when she was still very young and had her life’s work ahead of her.”

In contrast, Shannon LaNier chose not to wear a wig while posing as his great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather. “I didn’t want to become Jefferson,” says LaNier, who has gone to reunions at Monticello and co-authored the book Jefferson’s Children: The Story of One American Family. “My ancestor had his dreams—and now it’s up to all of us living in America today to make sure no one is excluded from the promise of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/bb/febba6fe-ae2f-44d9-a6f8-0598775e21e9/ruffle_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/27/0127a2bb-5ba1-46e0-ac0d-925b401c4fe5/thomasjefferson_shannonlanier.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/2a/232aa559-4061-4ad4-bc2b-854a09f1ddfc/shannon-lanier.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/e2/3ee21b97-b5f8-42a4-afe0-0140fd21c582/elizabeth-jenkins-sahlin.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/cd/78cd6549-ec1e-4c33-ac46-5333d1d6c85e/frederick-douglass.jpg)