How Sojourner Truth Used Photography to Help End Slavery

The groundbreaking orator embraced newfangled technology to make her message heard

:focal(724x1098:725x1099)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/93/4f93d5ed-1798-43f3-a6ac-0371689af287/sojourner_truth_cdv.jpg)

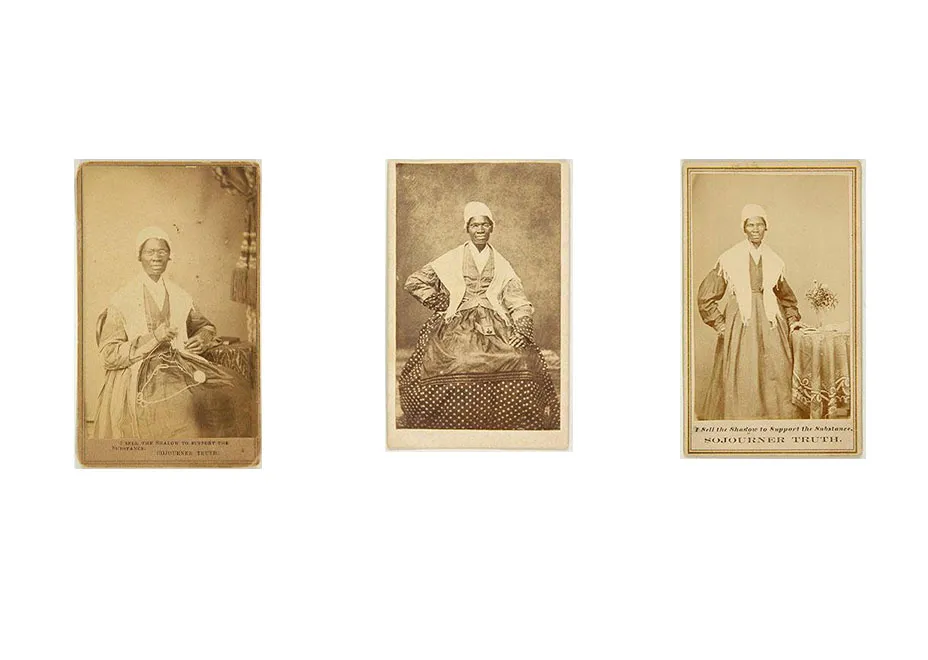

In the 1850s, a runaway slave who called herself Sojourner Truth electrified American audiences with her accounts of life in bondage. But her fame depended on more than her speaking skills: She was one of the first Americans to use photography to build her celebrity and earn a living. Now, a new exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive tells the story of how Truth used photography to help end slavery.

The exhibition, Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery, showcases the photographs the speaker sold to support herself. Each carte de visite—a small photograph mounted on a card—was, in days before television and social media, its own form of viral marketing.

The cards were so novel that they sparked a craze, The New York Times’ Andrea L. Volpe explains. Cheap, small and easy to collect and pass from hand to hand, they were tailor-made for both news buffs and sentimental folks. Soldiers and their sweethearts had them made as pocket-sized reminders of love affairs and family bonds. But they were also used as an early form of photographic advertising, spreading the never-before-seen faces of political leaders and public figures.

At first blush, Sojourner Truth seems like an unlikely photographic pioneer. Born into slavery sometime around 1797 under the name Isabella Baumfree, she was sold multiple times and beaten, harassed and forced to perform hard labor. In 1826, she walked away from her master’s New York farm in protest of his failure to live up to a promise to emancipate her ahead of a state law that would have made her free. She then sued John Dumont, her former master, for illegally selling her five-year-old son and won her case.

As a free woman, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth and experienced a religious conversion. She became an itinerant preacher and began to agitate for both the abolition of slavery and women’s rights, gaining fame for her witty style and her extemporaneous speeches like “Ain’t I a Woman?” To fund her speaking tours, which eventually included helping recruit black soldiers for the Union Army, Truth sold cartes de visite as souvenirs.

But Truth didn’t just embrace the newfangled technology: She worked it like no one had before. At the time, photographers held the copyright to cartes de visite regardless of who was on the front. Truth snuck around that convention by putting her own slogan—“I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance”—on the front of the cards so that people knew she was the owner. She also copyrighted her own image, and used proceeds from the sales to fund her speaking tours.

Visitors to the exhibit at BAMPFA can look at over 80 cartes de visites, including nine of Truth. The museum will also offer roundtables, films and a workshop where people can create their own cartes. The exhibition is comprised of gifts and loans of Truth-related materials by Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, whose book Enduring Truths: Sojourner's Shadows and Substance explores Truth's use of photography. It runs through October 23 and represents a chance to celebrate the life of a woman who knew the power of a photograph—and who use the medium to help combat one of history’s greatest evils.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)