NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

In 1868, Black Suffrage Was on the Ballot

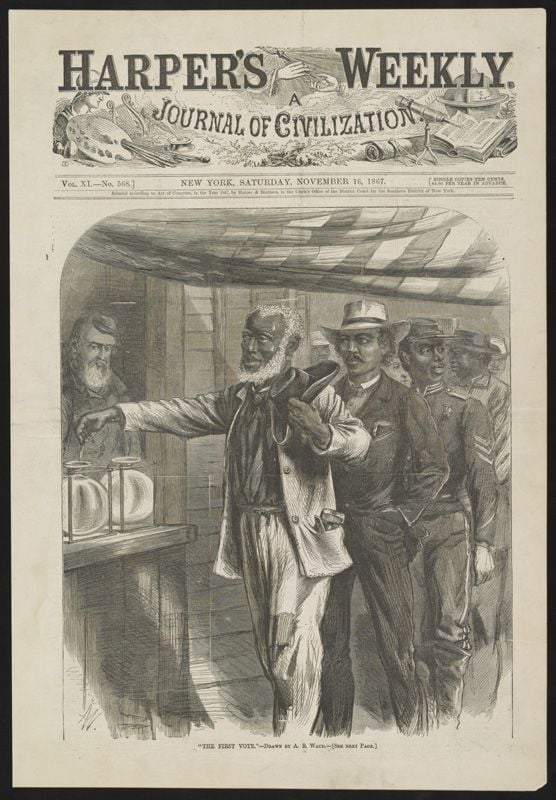

Every election season in the United States revolves around a set of issues—health care, foreign affairs, the economy. In 1868, at the height of the Reconstruction, the pressing issue was Black male suffrage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/NMAH-RWS2016-08997_Ed.jpg)

Every election season in the United States revolves around a set of issues—health care, foreign affairs, the economy. In 1868, at the height of the Reconstruction, the pressing issue was Black male suffrage. When voters went to the polls that November, they were asked to decide if and how their nation’s democracy should change to include Black men, millions of whom were newly freed from slavery. It was up to voters to decide: should Black men be granted the right to vote?

With the benefit of hindsight, we now know that this question was answered just two years later in 1870, with ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Fifteenth Amendment stipulates that citizens’ right to vote cannot be restricted based on "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." In 1868, however, there were no definite plans for a Fifteenth Amendment. The decision was still in voters’ hands.

Although African Americans had been fighting for freedom and full citizenship throughout U.S. history, their demands were generally ignored, rejected, or suppressed. Voting rights reflected this larger pattern. Before the Civil War, few states were willing to extend suffrage to groups other than white men. Among the Northern and Western states where slavery was outlawed, only a handful—most clustered in New England—allowed Black men to go to the polls. (Even in these states, Black women—like all women in the United States—were not allowed to vote. By 1868, most political leaders and activists had chosen to decouple the question of woman suffrage and Black male suffrage for strategic reasons. They did not think a majority of the nation would support giving women the ballot, and they feared that a push to secure women’s right to vote would doom efforts to enfranchise Black men. Both in the 1800s and more recently, writers sometimes obscure this aspect of the story by using universal terms like "Black suffrage").

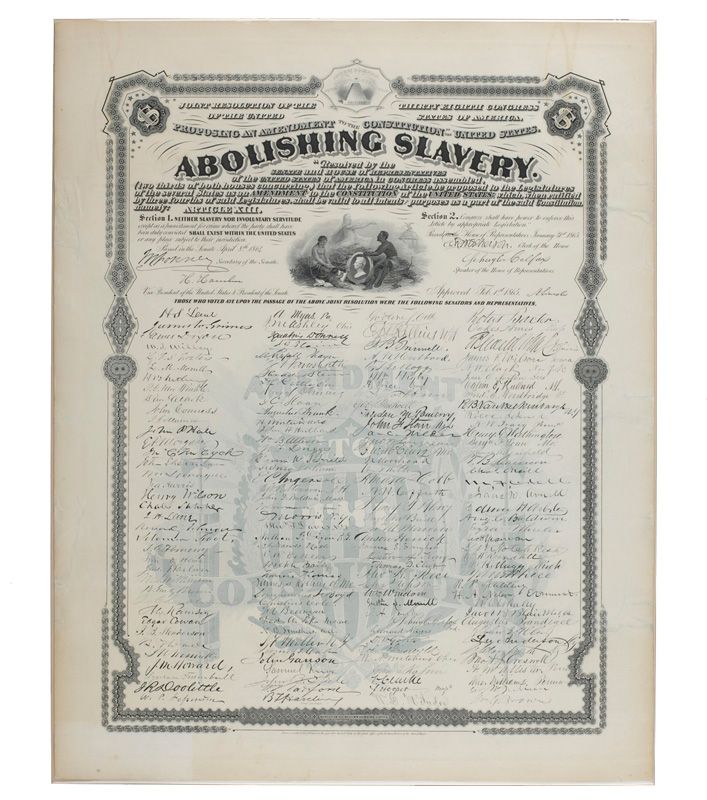

The Civil War transformed every aspect of life in the United States, including the political calculus behind Black male suffrage. With the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln committed the United States to ending slavery; he did not, however, define what freedom would look like for African Americans in a postwar world. After Lincoln’s assassination (and, later, the impeachment of his successor, President Andrew Johnson), members of the radical wing of the Republican Party took control of Congress and began to define what Lincoln’s "new birth of freedom" would look like, principally by supporting the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. Together, these amendments barred most forms of "slavery and involuntary servitude" nationwide, established birthright citizenship, and guaranteed the "privileges and immunities" and "due process" for all U.S. citizens. Neither amendment, however, directly addressed the issue of African Americans’ voting rights.

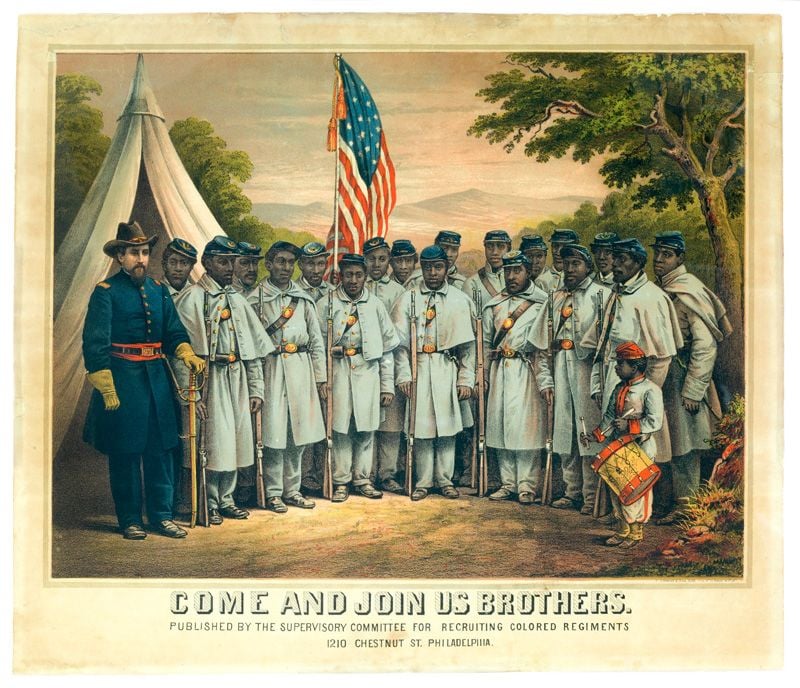

Of the various groups who fought to keep Black male suffrage at the forefront of political debate in the 1860s, none were more important than African Americans themselves. Well before the Civil War ended, African Americans made the case that their ability to protect their rights and freedoms depended on their right to shape politics directly at the polls. Many Black commentators pointed out the hypocrisy of asking African Americans to serve in the nation’s military but then denying them suffrage when they returned from the battlefield. Delegates at the the 1864 National Convention of Colored Men in Syracuse, New York, expressed this point eloquently in the conference’s address to the nation, asking "Are we good enough to use bullets, and not good enough to use ballots?"

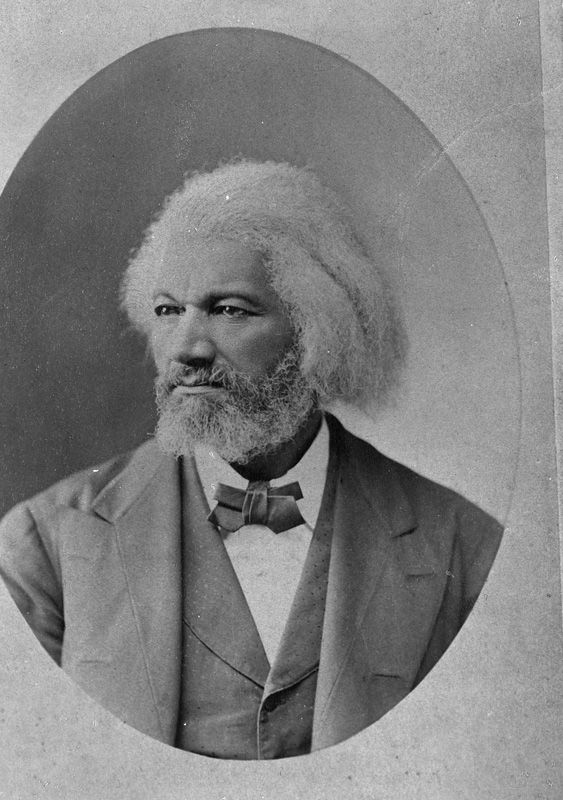

Black leaders also stressed that extending the franchise to Black men would safeguard the Union’s victory in the Civil War. As Frederick Douglass promised listeners during an 1863 address, formerly enslaved African Americans, if given the vote, would become the U.S. government’s "best protector against the traitors and the descendants of those traitors who will inherit the hate, the bitter revenge which shall crystallize all over the South, and seek to circumvent the government that they could not throw off." "You may need him to uphold in peace" Douglass cautioned, "as he is now upholding in war, the star-spangled banner."

After the Civil War, members of Congress took small steps towards enfranchising Black men. They began by eliminating racial qualifications for voting in places where the federal government had direct control over elections, such as Washington, D.C. and federal territories. National leaders’ efforts to establish Black male suffrage nationwide took a dramatic leap forward in 1867. Fresh from victories in a midterm election, Republicans in Congress overrode President Johnson’s veto to pass a series of Reconstruction Acts. The first act, approved in March 1867, required former Confederate states to form new governments that enfranchised all "male citizens...twenty-one years old and upward, of whatever race, color, or previous condition" before they could be readmitted to the Union.

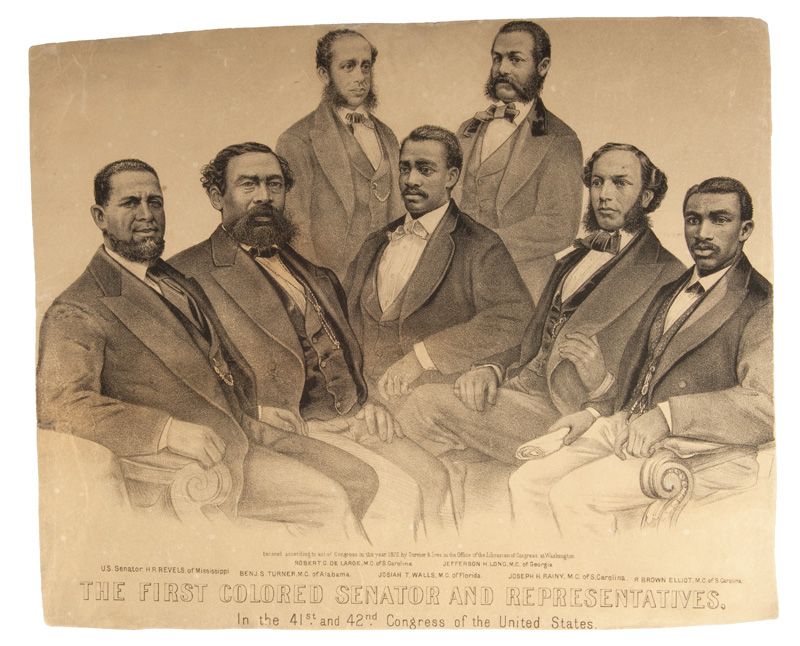

Under these new laws (and with the backing of the U.S. military) Black men in most of the former slaveholding states could vote and run for office. Tens of thousands did. Their votes at the state level created the nation’s first biracial state governments. They also laid the foundation for the first Black representatives in Congress.

Ironically, in 1868, the main political hurdle that Black male suffrage faced was winning approval in the North and West—regions of the United States that had remained loyal to the Union cause during the Civil War. In states that had fought for the Union during the Civil War, legislators could not use the Reconstruction Acts to directly intervene in elections and shape qualifications for voting. At the same time, state-level referendums that would have extended suffrage to Black men in the North and West stalled and failed in the mid-1860s. In election after election, Northern and Western voters made it clear that, while they would support enfranchising Black men in the South, they had little interest in adding them to the electorate in their home states.

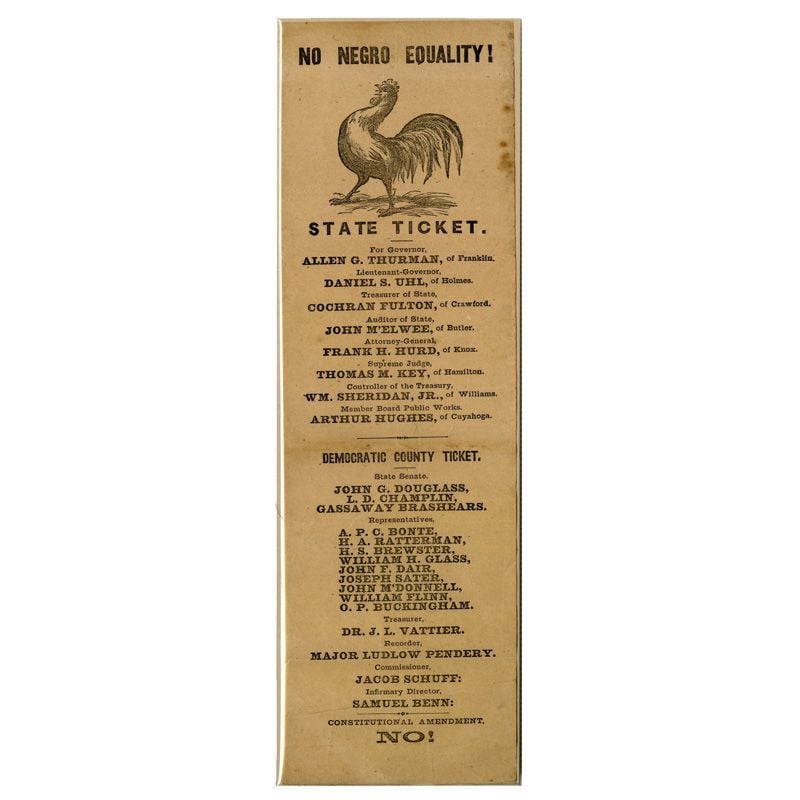

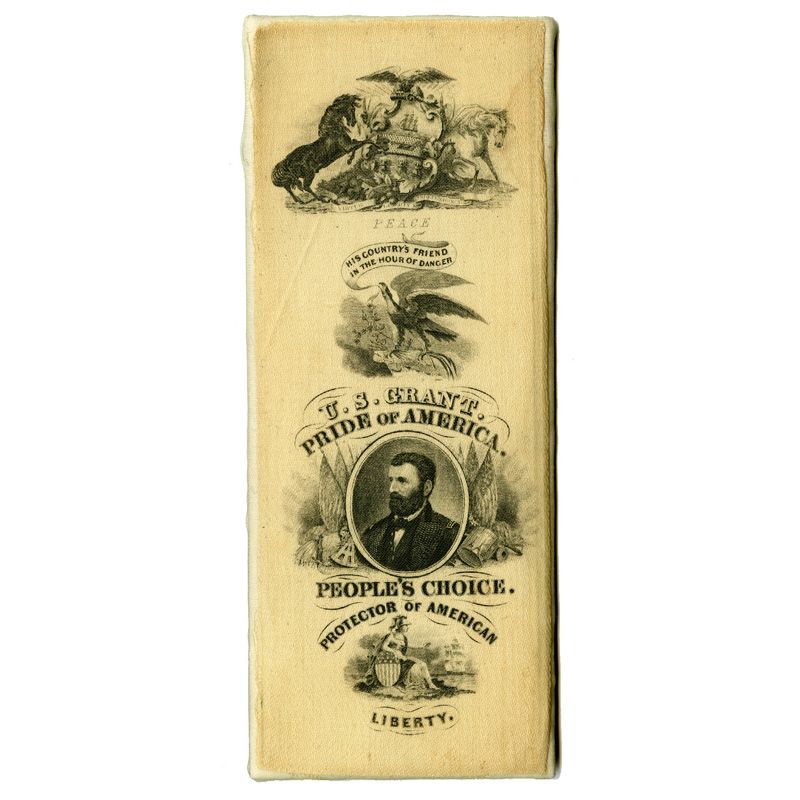

The unresolved debate over Black male suffrage shaped the presidential election of 1868. Fearful that Northern voters would reject their party’s approach to Reconstruction, the Republican Party nominated a candidate with guaranteed broad appeal throughout the North and West: Ulysses S. Grant. After much debate, the Democratic Party chose Horatio Seymour, then governor of New York, as their candidate.

The Democratic Party’s platform openly criticized how the Reconstruction acts had stripped former Confederate states of their right to regulate voting at the state level, free of federal oversight. This was a thinly veiled attack on Black male suffrage. The party’s candidate for vice president, Francis Preston Blair Jr., made the attack explicit in his acceptance letter, which was read at that year’s convention. Blair condemned Republican leaders for substituting "as electors in place of men of our race. . .a host of ignorant negroes who are supported in idleness with the public money."

Although the Republican Party platform continued to support extending the right to vote to all Southern men, irrespective of race, it fell far short of calling for Black male suffrage nationwide. Rather than risk alienating white voters in the North and West, the party pledged to leave states that had remained loyal to the Union the authority to regulate voting rights, even if that meant those states continued to deprive Black men of the vote.

Ulysses S. Grant’s narrow victory in 1868 encouraged members of the Republican Party to reconsider their position. On one hand, many contemporaries believed that the party’s support for Black men’s voting rights—tepid though it was—had cost it votes. At the same time, Republican leaders were cheered to see that newly-enfranchised Black men throughout the South had come out to support Grant’s election. Enfranchising Black men nationwide would, they hoped, secure their party’s political future.

Other elected officials who supported Black male suffrage for less politically motivated reasons were cheered by the moderate victories the cause had secured in 1868, as voters in states like Iowa and Minnesota had voted in favor of laws that allowed Black men to vote. Though conflicting, these various signals were enough to convince a majority of Republicans in Congress that their party should act quickly to enfranchise Black men nationwide before the political winds shifted against them.

Therefore, at the start of Congress's session in late 1868, Republican members of Congress were primed to support an amendment to the Constitution that would nationalize Black male suffrage. Instead of whether a Fifteenth Amendment should be created, the question became: what should it say?