Leopold and Loeb’s Criminal Minds

In defense of murderers Leopold and Loeb, attorney Clarence Darrow thwarted a nation’s call for vengeance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/leopoldloeb_aug08_631.jpg)

Nathan Leopold (left) and his lover Richard Loeb confessed that they had kidnapped and murdered Bobby Franks solely for the thrill of the experience. Underwood & Underwood/ Corbis

Nathan Leopold was in a bad mood. That evening, on November 10, 1923, he had agreed to drive with his friend and lover, Richard Loeb, from Chicago to the University of Michigan—a journey of six hours—to burglarize Loeb's former fraternity, Zeta Beta Tau. But they had managed to steal only $80 in loose change, a few watches, some penknives and a typewriter. It had been a big effort for very little reward and now, on the journey back to Chicago, Leopold was querulous and argumentative. He complained bitterly that their relationship was too one-sided: he always joined Loeb in his escapades, yet Loeb held him at arm's length.

Eventually Loeb managed to quiet Leopold's complaints with reassurances of his affection and loyalty. And as they continued to drive along the country roads in the direction of Chicago, Loeb started to talk about his idea to carry out the perfect crime. They had committed several burglaries together, and they had set fires on a couple of occasions, but none of their misdeeds had been reported in the newspapers. Loeb wanted to commit a crime that would set all of Chicago talking. What could be more sensational than the kidnapping and murder of a child? If they demanded a ransom from the parents, so much the better. It would be a difficult and complex task to obtain the ransom without being caught. To kidnap a child would be an act of daring—and no one, Loeb proclaimed, would ever know who had accomplished it.

Leopold and Loeb had met in the summer of 1920. Both boys had grown up in Kenwood, an exclusive Jewish neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. Leopold was a brilliant student who matriculated at the University of Chicago at the age of 15. He also earned distinction as an amateur ornithologist, publishing two papers in The Auk, the leading ornithological journal in the United States. His family was wealthy and well connected. His father was an astute businessman who had inherited a shipping company and had made a second fortune in aluminum can and paper box manufacturing. In 1924, Leopold, 19, was studying law at the University of Chicago; everyone expected that his career would be one of distinction and honor.

Richard Loeb, 18, also came from a wealthy family. His father, the vice president of Sears, Roebuck & Company, possessed an estimated fortune of $10 million. The third son in a family of four boys, Loeb had distinguished himself early, graduating from University High School at the age of 14 and matriculating later the same year at the University of Chicago. His experience as a student at the university, however, was not a happy one. Loeb's classmates were several years older and he earned only mediocre grades. At the end of his sophomore year, he transferred to the University of Michigan, where he remained a lackluster student who spent more time playing cards and reading dime novels than sitting in the classroom. And he became an alcoholic during his years at Ann Arbor. Nevertheless he managed to graduate from Michigan, and in 1924 he was back in Chicago, taking graduate courses in history at the university.

The two teenagers had renewed their friendship upon Loeb's return to Chicago in the fall of 1923. They seemed to have little in common—Loeb was gregarious and extroverted; Leopold misanthropic and aloof—yet they soon became intimate companions. And the more Leopold learned about Loeb, the stronger his attraction for the other boy. Loeb was impossibly good-looking: slender but well built, tall, with brown-blond hair, humorous eyes and a sudden attractive smile; and he had an easy, open charm. That Loeb would often indulge in purposeless, destructive behavior—stealing cars, setting fires and smashing storefront windows—did nothing to diminish Leopold's desire for Loeb's companionship.

Loeb loved to play a dangerous game, and he sought always to raise the stakes. His vandalism was a source of intense exhilaration. It pleased him also that he could rely on Leopold to accompany him on his escapades; a companion whose admiration reinforced Loeb's self-image as a master criminal. True, Leopold was annoyingly egotistical. He had an irritating habit of bragging about his supposed accomplishments, and it quickly became tiresome to listen to Leopold's empty, untrue boast that he could speak 15 languages. Leopold also had a tedious obsession with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. He would talk endlessly about the mythical superman who, because he was a superman, stood outside the law, beyond any moral code that might constrain the actions of ordinary men. Even murder, Leopold claimed, was an acceptable act for a superman to commit if the deed gave him pleasure. Morality did not apply in such a case.

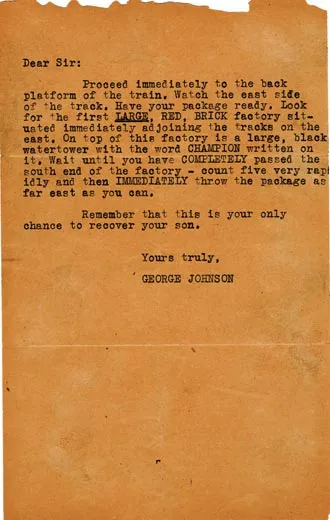

Leopold had no objection to Loeb's plan to kidnap a child. They spent long hours together that winter, discussing the crime and planning its details. They decided upon a $10,000 ransom, but how would they obtain it? After much debate they came up with a plan they thought foolproof: they would direct the victim's father to throw a packet containing the money from the train that traveled south of Chicago along the elevated tracks west of Lake Michigan. They would be waiting below in a car; as soon as the ransom hit the ground, they would scoop it up and make good their escape.

On the afternoon of May 21, 1924, Leopold and Loeb drove their rental car slowly around the streets of the South Side of Chicago, looking for a possible victim. At 5 o'clock, after driving around Kenwood for two hours, they were ready to abandon the kidnapping for another day. But as Leopold drove north along Ellis Avenue, Loeb, sitting in the rear passenger seat, suddenly saw his cousin, Bobby Franks, walking south on the opposite side of the road. Bobby's father, Loeb knew, was a wealthy businessman who would be able to pay the ransom. He tapped Leopold on the shoulder to indicate they had found their victim.

Leopold turned the car in a circle, driving slowly down Ellis Avenue, gradually pulling alongside Bobby.

"Hey, Bob," Loeb shouted from the rear window. The boy turned slightly to see the Willys-Knight stop by the curb. Loeb leaned forward, into the front passenger seat, to open the front door.

"Hello, Bob. I'll give you a ride."

The boy shook his head—he was almost home.

"No, I can walk."

"Come on in the car; I want to talk to you about the tennis racket you had yesterday. I want to get one for my brother."

Bobby had moved closer now. He was standing by the side of the car. Loeb looked at him through the open window. Bobby was so close....Loeb could have grabbed him and pulled him inside, but he continued talking, hoping to persuade the boy to climb into the front seat.

Bobby stepped onto the running board. The front passenger door was open, inviting the boy inside...and then suddenly Bobby slid himself into the front seat, next to Leopold.

Loeb gestured toward his companion, "You know Leopold, don't you?"

Bobby glanced sideways and shook his head—he did not recognize him.

"No."

"You don't mind [us] taking you around the block?"

"Certainly not." Bobby turned around in the seat to face Loeb; he smiled at his cousin with an open, innocent grin, ready to banter about his success in yesterday's tennis game.

The car slowly accelerated down Ellis Avenue. As it passed 49th Street, Loeb felt on the car seat beside him for the chisel. Where had it gone? There it was! They had taped up the blade so that the blunt end—the handle—could be used as a club. Loeb felt it in his hand. He grasped it more firmly.

At 50th Street, Leopold turned the car left. As it made the turn, Bobby looked away from Loeb and glanced toward the front of the car.

Loeb reached over the seat. He grabbed the boy from behind with his left hand, covering Bobby's mouth to stop him from crying out. He brought the chisel down hard—it smashed into the back of the boy's skull. Once again he pounded the chisel into the skull with as much force as possible—but the boy was still conscious. Bobby had now twisted halfway around in the seat, facing back to Loeb, desperately raising his arms as though to protect himself from the blows. Loeb smashed the chisel down two more times into Bobby's forehead, but still he struggled for his life.

The fourth blow had gashed a large hole in the boy's forehead. Blood from the wound was everywhere, spreading across the seat, splashed onto Leopold's trousers, spilling onto the floor.

It was inexplicable, Loeb thought, that Bobby was still conscious. Surely those four blows would have knocked him out?

Loeb reached down and pulled Bobby suddenly upwards, over the front seat into the back of the car. He jammed a rag down the boy's throat, stuffing it down as hard as possible. He tore off a large strip of adhesive tape and taped the mouth shut. Finally! The boy's moaning and crying had stopped. Loeb relaxed his grip. Bobby slid off his lap and lay crumpled at his feet.

Leopold and Loeb had expected to carry out the perfect crime. But as they disposed of the body—in a culvert at a remote spot several miles south of Chicago—a pair of eyeglasses fell from Leopold's jacket onto the muddy ground. Upon returning to the city, Leopold dropped the ransom letter into a post box; it would arrive at the Franks house at 8 o'clock the next morning. The following day, a passerby spotted the body and notified the police. The Franks family confirmed the identity of the victim as that of 14-year-old Bobby. The perfect crime had unraveled and now there was no longer any thought, on the part of Leopold and Loeb, of attempting to collect the ransom.

By tracing Leopold's ownership of the eyeglasses, the state's attorney, Robert Crowe, was able to determine that Leopold and Loeb were the leading suspects.

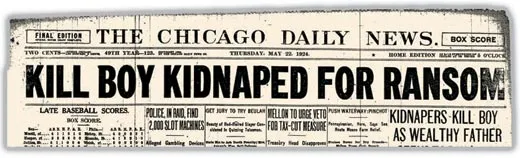

Ten days after the murder, on May 31, both boys confessed and demonstrated to the state's attorney how they had killed Bobby Franks.

Crowe boasted to the press that it would be "the most complete case ever presented to a grand or petit jury" and that the defendants would certainly hang. Leopold and Loeb had confessed and shown the police crucial evidence—the typewriter used for the ransom letter—that linked them to the crime.

The trial, Crowe quickly realized, would be a sensation. Nathan Leopold admitted they had murdered Bobby solely for the thrill of the experience. ("A thirst for knowledge is highly commendable, no matter what extreme pain or injury it may inflict upon others," Leopold had told a newspaper reporter. "A 6-year-old-boy is justified in pulling the wings from a fly, if by so doing he learns that without wings the fly is helpless.") The defendants' wealth, their intellectual ability, the high regard within Chicago for their families and the capricious nature of the homicide—everything combined to make the crime one of the most intriguing murders in the history of Cook County.

Crowe also realized that he could turn the case to his own advantage. He was 45 years old, yet already he had had an illustrious career as chief justice of the criminal court and, since 1920, as state's attorney of Cook County. Crowe was a leading figure in the Republican Party with a realistic chance of winning election as Chicago's next mayor. To send Leopold and Loeb to the gallows for their murder of a child would, no doubt, find favor with the public.

Indeed, the public's interest in the trial was driven by more than lurid fascination with the grisly details of the case. Sometime within the past few years the country had experienced a shift in public morality. Women now bobbed their hair, smoked cigarettes, drank gin and wore short skirts; sexuality was everywhere and young people were eagerly taking advantage of their new freedoms. The traditional ideals—centered on work, discipline and self-denial—had been replaced by a culture of self-indulgence. And what single event could better illustrate the dangers of such a transformation than the heinous murder of Bobby Franks? The evangelical preacher Billy Sunday, passing through Chicago on his way to Indiana, warned that the killing could be "traced to the moral miasma which contaminates some of our ‘young intellectuals.' It is now considered fashionable for higher education to scoff at God....Precocious brains, salacious books, infidel minds—all these helped to produce this murder."

But while Crowe could count on the support of an outraged public, he faced a daunting adversary in the courtroom. The families of the confessed murderers had hired Clarence Darrow as defense attorney. By 1894, Darrow had achieved notoriety within Cook County as a clever speaker, an astute lawyer and a champion of the weak and defenseless. One year later, he would become the most famous lawyer in the country, when he successfully defended Socialist labor leader Eugene Debs against conspiracy charges that grew out of a strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company. Crowe could attest firsthand to Darrow's skills. In 1923, Darrow had humiliated him in the corruption trial of Fred Lundin, a prominent Republican politician.

Like Crowe, Darrow knew that he might be able to play the trial of Leopold and Loeb to his advantage. Darrow was passionately opposed to the death penalty; he saw it as a barbaric and vengeful punishment that served no purpose except to satisfy the mob. The trial would provide him with the means to persuade the American public that the death penalty had no place in the modern judicial system.

Darrow's opposition to capital punishment found its greatest source of inspiration in the new scientific disciplines of the early 20th century. "Science and evolution teach us that man is an animal, a little higher than the other orders of animals; that he is governed by the same natural laws that govern the rest of the universe," he wrote in the magazine Everyman in 1915. Darrow saw confirmation of these views in the field of dynamic psychiatry, which emphasized infantile sexuality and unconscious impulses and denied that human actions were freely chosen and rationally arranged. Individuals acted less on the basis of free will and more as a consequence of childhood experiences that found their expression in adult life. How, therefore, Darrow reasoned, could any individual be responsible for his or her actions if they were predetermined?

Endocrinology—the study of the glandular system—was another emerging science that seemed to deny the existence of individual responsibility. Several recent scientific studies had demonstrated that an excess or deficiency of certain hormones produced mental and physical alterations in the afflicted person. Mental illness was closely correlated with physical symptoms that were a consequence of glandular action. Crime, Darrow believed, was a medical problem. The courts, guided by psychiatry, should abandon punishment as futile and in its place should determine the proper course of medical treatment for the prisoner.

Such views were anathema to Crowe. Could any philosophy be more destructive of social harmony than Darrow's? The murder rate in Chicago was higher than ever, yet Darrow would do away with punishment. Crime, Crowe believed, would decline only through the more rigorous application of the law. Criminals were fully responsible for their actions and should be treated as such. The stage was set for an epic courtroom battle.

Still, in terms of legal strategy, the burden fell heaviest on Darrow. How would he plead his clients? He could not plead them innocent, since both had confessed. There had been no indication that the state's attorney had obtained their statements under duress. Would Darrow plead them not guilty by reason of insanity? Here too was a dilemma, since both Leopold and Loeb appeared entirely lucid and coherent. The accepted test of insanity in the Illinois courts was the inability to distinguish right from wrong and, by this criterion, both boys were sane.

On July 21, 1924, the opening day of court, Judge John Caverly indicated that the attorneys for each side could present their motions. Darrow could ask the judge to appoint a special commission to determine if the defendants were insane. The results of an insanity hearing might abrogate the need for a trial; if the commission decided that Leopold and Loeb were insane, Caverly could, on his own initiative, send them to an asylum.

It was also possible that the defense would ask the court to try each defendant separately. Darrow, however, already had expressed his belief that the killing was a consequence of each defendant influencing the other. There was no indication, therefore, that the defense would argue for a severance.

Nor was it likely that Darrow would ask the judge to delay the start of the trial beyond August 4, its assigned date. Caverly's term as chief justice of the criminal court would expire at the end of August. If the defense requested a continuance, the new chief justice, Jacob Hopkins, might assign a different judge to hear the case. But Caverly was one of the more liberal justices on the court; he had never voluntarily sentenced a defendant to death; and it would be foolish for the defense to request a delay that might remove him from the case.

Darrow might also present a motion to remove the case from the Cook County Criminal Court. Almost immediately after the kidnapping, Leopold had driven the rental car across the state line into Indiana. Perhaps Bobby had died outside Illinois and therefore the murder did not fall within the jurisdiction of the Cook County court. But Darrow had already declared that he would not ask for a change of venue and Crowe, in any case, could still charge Leopold and Loeb with kidnapping, a capital offense in Illinois, and hope to obtain a hanging verdict.

Darrow chose none of these options. Nine years earlier, in an otherwise obscure case, Darrow had pleaded Russell Pethick guilty of the murder of a 27-year-old housewife and her infant son but had asked the court to mitigate the punishment on account of the defendant's mental illness. Now he would attempt the same strategy in the defense of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb. His clients were guilty of murdering Bobby Franks, he told Caverly. Nevertheless he wished the judge to consider three mitigating factors in determining their punishment: their age, their guilty plea and their mental condition.

It was a brilliant maneuver. By pleading them guilty, Darrow avoided a trial by jury. Caverly would now preside over a hearing to determine punishment—a punishment that might range from the death penalty to a minimum of 14 years in prison. Clearly it was preferable for Darrow to argue his case before a single judge than before 12 jurors susceptible to public opinion and Crowe's inflammatory rhetoric.

Darrow had turned the case on its head. He no longer needed to argue insanity in order to save Leopold and Loeb from the gallows. He now needed only to persuade the judge that they were mentally ill—a medical condition, not at all equivalent or comparable to insanity—to obtain a reduction in their sentence. And Darrow needed only a reduction from death by hanging to life in prison to win his case.

And so, during July and August 1924, the psychiatrists presented their evidence. William Alanson White, the president of the American Psychiatric Association, told the court that both Leopold and Loeb had experienced trauma at an early age at the hands of their governesses. Loeb had grown up under a disciplinary regimen so exacting that, in order to escape punishment, he had had no other recourse but to lie to his governess, and so, in White's account at least, he had been set on a path of criminality. "He considered himself the master criminal mind of the century," White testified, "controlling a large band of criminals, whom he directed; even at times he thought of himself as being so sick as to be confined to bed, but so brilliant and capable of mind...[that] the underworld came to him and sought his advice and asked for his direction." Leopold also had been traumatized, having been sexually intimate with his governess at an early age.

Other psychiatrists—William Healy, the author of The Individual Delinquent, and Bernard Glueck, professor of psychiatry at the New York Postgraduate School and Hospital—confirmed that both boys possessed a vivid fantasy life. Leopold pictured himself as a strong and powerful slave, favored by his sovereign to settle disputes in single-handed combat. Each fantasy interlocked with the other. Loeb, in translating his fantasy of being a criminal mastermind into reality, required an audience for his misdeeds and gladly recruited Leopold as a willing participant. Leopold needed to play the role of the slave to a powerful sovereign—and who, other than Loeb, was available to serve as Leopold's king?

Crowe had also recruited prominent psychiatrists for the prosecution. They included Hugh Patrick, president of the American Neurological Association; William Krohn and Harold Singer, authors of Insanity and the Law: A Treatise on Forensic Psychiatry; and Archibald Church, professor of mental diseases and medical jurisprudence at Northwestern University. All four testified that neither Leopold nor Loeb displayed any sign of mental derangement. They had examined both prisoners in the office of the state's attorney shortly after their arrest. "There was no defect of vision," Krohn testified, "no defect of hearing, no evidence of any defect of any of the sense paths or sense activities. There was no defect of the nerves leading from the brain as evidenced by gait or station or tremors."

Each set of psychiatrists—one for the state, the other for the defense—contradicted the other. Few observers noticed that each side spoke for a different branch of psychiatry and was, therefore, separately justified in reaching its verdict. The expert witnesses for the state, all neurologists, had found no evidence that any organic trauma or infection might have damaged either the cerebral cortex or the central nervous system of the defendants. The conclusion reached by the psychiatrists for the prosecution was, therefore, a correct one—there was no mental disease.

The psychiatrists for the defense—White, Glueck and Healy—could assert, with equal justification, that, according to their understanding of psychiatry, an understanding informed by psychoanalysis, the defendants had suffered mental trauma during childhood that had damaged each boy's ability to function competently. The result was compensatory fantasies that had led directly to the murder.

Most commentators, however, were oblivious to the epistemological gulf that separated neurology from psychoanalytic psychiatry. The expert witnesses all claimed to be psychiatrists, after all; and it was, everyone agreed, a dark day for psychiatry when leading representatives of the profession could stand up in court and contradict each other. If men of national reputation and eminence could not agree on a common diagnosis, then could any value be attached to a psychiatric judgment? Or perhaps each group of experts was saying only what the lawyers required them to say—for a fee, of course.

It was an evil that contaminated the entire profession, thundered the New York Times, in an editorial similar to dozens of others during the trial. The experts in the hearing were "of equal authority as alienists and psychiatrists," apparently in possession of the same set of facts, who, nevertheless, gave out "opinions exactly opposite and contradictory as to the past and present condition of the two prisoners.... Instead of seeking truth for its own sake and with no preference as to what it turns out to be, they are supporting, and are expected to support, a predetermined purpose....That the presiding Judge," the editorial writer concluded sorrowfully, "is getting any help from those men toward the forming of his decision hardly is to be believed."

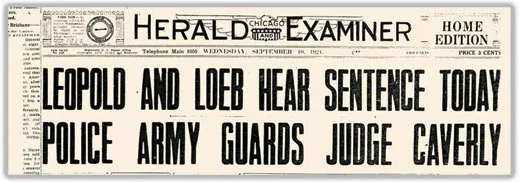

At 9:30 on the morning of September 10, 1924, Caverly prepared to sentence the prisoners. The final day of the hearing was to be broadcast live over station WGN, and throughout the city, groups of Chicagoans clustered around radio sets to listen. The metropolis had paused in its morning bustle to hear the verdict.

Caverly's statement was brief. In determining punishment, he gave no weight to the guilty plea. Normally a guilty plea could mitigate punishment if it saved the prosecution the time and trouble of demonstrating culpability; but that had not been the case on this occasion.

The psychiatric evidence also could not be considered in mitigation. The defendants, Caverly stated, "have been shown in essential respects to be abnormal....The careful analysis made of the life history of the defendants and of their present mental, emotional and ethical condition has been of extreme interest....And yet the court feels strongly that similar analyses made of other persons accused of crime would probably reveal similar or different abnormalities....For this reason the court is satisfied that his judgment in the present case cannot be affected thereby."

Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb had been 19 and 18 years old, respectively, at the time of the murder. Did their youth mitigate the punishment? The prosecuting attorneys, in their concluding statements to the court, had emphasized that many murderers of similar age had been executed in Cook County; and none had planned their deeds with as much deliberation and forethought as Leopold and Loeb. It would be outrageous, Crowe had argued, for the prisoners to escape the death penalty when others—some even younger than 18—had been hanged.

Yet, Caverly decided he would hold back from imposing the extreme penalty on account of the age of the defendants. He sentenced each defendant to 99 years for the kidnapping and life in prison for the murder. "The court believes," Caverly stated, "that it is within his province to decline to impose the sentence of death on persons who are not of full age. This determination appears to be in accordance with the progress of criminal law all over the world and with the dictates of enlightened humanity."

The verdict was a victory for the defense, a defeat for the state. The guards allowed Leopold and Loeb to shake Darrow's hand before escorting the prisoners back to their cells. Two dozen reporters crowded around the defense table to hear Darrow's response to the verdict and, even in his moment of victory, Darrow was careful not to seem too triumphal: "Well, it's just what we asked for but...it's pretty tough." He pushed back a lock of hair that had fallen over his forehead, "It was more of a punishment than death would have been."

Crowe was furious at the judge's decision. In his statement to the press, Crowe made sure everyone knew whom to blame: "The state's attorney's duty was fully performed. He is in no measure responsible for the decision of the court. The responsibility for that decision rests with the judge alone." Later that evening, however, Crowe's rage would emerge in full public view, when he issued another, more inflammatory statement: "[Leopold and Loeb] had the reputation of being immoral...degenerates of the worst type....The evidence shows that both defendants are atheists and followers of the Nietzschean doctrines...that they are above the law, both the law of God and the law of man....It is unfortunate for the welfare of the community that they were not sentenced to death."

As for Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, their fates would take divergent paths. In 1936, inside Stateville Prison, James Day, a prisoner serving a sentence for grand larceny, stabbed Loeb in the shower room and despite the best efforts of the prison doctors, Loeb, then 30 years old, died of his wounds shortly afterward.

Leopold served 33 years in prison until he won parole in 1958. At the parole hearing, he was asked whether he realized that every media outlet in the country would want an interview with him. Already there was a rumor that Ed Murrow, the CBS correspondent, wanted him to appear on his television show "See It Now." "I don't want any part of lecturing, television or radio, or trading on the notoriety," Leopold replied. The confessed murderer who had once deemed himself a superman stated, "All I want, if I am so lucky as to ever see freedom again, is to try to become a humble little person."

Upon his release, Leopold moved to Puerto Rico, where he lived in relative obscurity, studying for a degree in social work at the University of Puerto Rico, writing a monograph on the birds of the island, and, in 1961, marrying Trudi Garcia de Quevedo, the expatriate widow of a Baltimore physician. During the 1960s, Leopold was finally able to travel to Chicago. He returned to the city often, to see old friends, to tour the South Side neighborhood near the university and to place flowers on the graves of his mother and father and two brothers.

It had been so long ago—that summer of 1924, in the stuffy courtroom on the sixth floor of the Cook County Criminal Court—and now he was the sole survivor. The crime had passed into legend; its thread had been woven into the tapestry of Chicago's past; and when Nathan Leopold, at age 66, died in Puerto Rico of a heart attack on August 29, 1971, the newspapers wrote of the murder as the crime of the century, an event so inexplicable and so shocking that it would never be forgotten.

© 2008 by Simon Baatz, adapted from For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder that Shocked Chicago, published by HarperCollins.