Five Powerful Stories That Are Perfect for Women’s Equality Day

From Congress to the Olympics, women have made their mark on history

:focal(801x602:802x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/08/f5/08f5a432-376d-459a-9465-266c5db66e7e/smithsonian_american_women_voices_cover.jpg)

1. Sojourner Truth's Image as Activism

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/bb/33bbe77e-5b6f-4ac9-a264-ce93b29c26b8/sojourner_truth_image.jpg)

A moving speaker, Truth traveled the country from the mid-1840s until her death in 1883, advocating for equal rights. She paid for the first printing of her Narrative of Sojourner Truth (written with friends) by selling her photographs at rallies and advertising them in antislavery publications. She also purchased a home in Battle Creek, Michigan, with the proceeds from these sales and her speaking engagements.

Sojourner Truth was born Isabella Baumfree around 1797 in upstate New York. Dutch was her first language, and she never learned to read or write in English. Separated from her parents around the age of thirteen and sold several times afterward, a field accident removed part of her index finger on her right hand, leaving it badly mangled. This disfigurement is visible in several of the portraits that she would later sell. Truth escaped slavery in 1826 around the age of thirty. After a religious conversion at forty-six, she changed her name to one she felt better reflected her life’s purpose.The great Black statesman Frederick Douglass dismissed her as “uncultured” because of her illiteracy, but her supporters knew better. Truth believed that although she could not read a book, she could read people. Her empathy, coupled with her religious convictions, gave her a dynamism that would capture the public imagination well beyond her lifetime, continuing to inspire others to help to end racial and gender oppression. —Rhea L. Combs

2. The Suffrage Wagon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/08/f5/08f5a432-376d-459a-9465-266c5db66e7e/smithsonian_american_women_voices_cover.jpg)

Yet women fighting for change found allies in their quest for greater equality. By the mid-nineteenth century, women across the country were forming suffrage associations and reaching for voting rights, hoping that the ballot would be a powerful weapon in the fight for civil and cultural equality.

When abolitionists and early suffrage leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucy Stone strongly disagreed over how to respond to the exclusion of women from post–Civil War voting rights amendments, they founded rival organizations with different strategies. Stanton and Anthony blended suffrage with controversial reforms in women’s rights, including changes in divorce law, and advocated a constitutional amendment enfranchising women. Stone focused on organizing statewide campaigns to win the vote. They would ultimately merge their associations, and some of their tactics.In the 1870s, Stone began using an unpainted wagon as a podium at speaking engagements and to distribute her newspaper, Woman’s Journal. In 1913, suffragist and labor activist Elisabeth Freeman took it on a well-publicized trip from New York to Boston, hauling a hurdy-gurdy organ to draw crowds. It was still used for suffrage publicity, but by then the wagon had been painted. It made the trip to Boston covered in slogans advertising Woman’s Journal and calling for equal pay, just labor laws, and the vote for women of all classes. —Lisa Kathleen Graddy

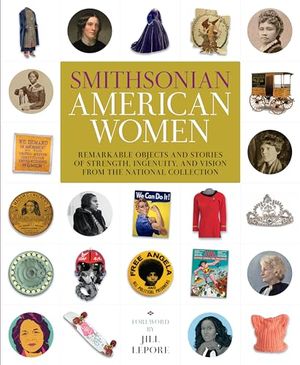

Smithsonian American Women: Remarkable Objects and Stories of Strength, Ingenuity, and Vision from the National Collection

An inspiring and surprising celebration of U.S. women's history told through Smithsonian artifacts illustrating women's participation in science, art, music, sports, fashion, business, religion, entertainment, military, politics, activism, and more.

3. Challenging Gender Boundaries on Stage

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/91/bc/91bc40f7-e2b0-4cb2-9a87-e3baa7658f83/charlotte_cushman.jpg)

Playing Wolsey broke with a century of theatrical precedent. Women (including Cushman) had long played tragic male characters such as Romeo and Hamlet, donning tights that exposed legs normally concealed under dresses. By choosing to portray Henry VIII’s ambitious and machinating chief minister, Cushman not only broadened the scope of characters available to women but also picked one whose loose-fitting robes put the emphasis on her acting rather than her body.

In an unusual move for a young woman, Cushman became a teenage performer to support her family. As an adult, she funded and lived in a community of what she and her friends called “jolly female bachelors.” All the romantic relationships documented in her personal papers were with women.At a time before such words as lesbian, queer, and transgender came into use, most Americans thought that not having relationships with men made Cushman chaste and pure. Cushman herself strove to confirm this view and ordered her partners and lovers to burn her letters to preserve her public image. But in the decades after her death in 1876, as homosexuality among women became more recognized—and ridiculed—she fell out of public favor and was largely forgotten. Only in recent years has her story been recovered by scholars and activists, who see Cushman as an early advocate for a woman’s right to be whoever she wants to be—on and off the stage. —Kenneth Cohen

4. The "Summer of the Women" 1996 Olympics

American women have shared the Olympic spotlight with men since 1900, but in the 1996 Atlanta games, they dominated. That summer, a record-breaking 292 female athletes took the fields, courts, track, and pool by storm, outnumbering men on the 555-member US team and marking the largest number of women to represent a nation in the history of the games.These female athletes were among the generation raised after Title IX, a law designed to eliminate gender inequality in college education and athletics. When Title IX passed in 1972, only 15 percent of college athletes were women; by 1996, that number had soared above 40 percent.

In 1996, women competed on the soccer field for the first time. Mia Hamm led Team USA on an undefeated run to the gold. The win kicked off an era of triumph—including a celebrated 1999 World Cup victory—and generated an explosion of interest in soccer among girls.The women’s basketball team swept the Olympic tournament, claiming gold and serving as a springboard for a professional women’s league. The following year, Rebecca Lobo helped found the new Women’s National Basketball Association.

Before 1996, a number of US women won gold in gymnastics, but in Atlanta, the “Magnificent Seven” became the first US team to reach the championship podium, defeating perennial favorites Russia and Romania. Among the seven, Dominique Dawes became the first Black athlete from any country to win gold in gymnastics.Inspiring generations, the 1996 women of Team USA sparked public conversation surrounding women’s expanding role in sports, paving the way for future generations of female athletes and Olympians. —Eric W. Jentsch

5. A Woman's Seat at the Political Table

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/67/eb/67ebba68-7c8d-42b7-88df-cb9539921f61/frances_perkins.jpg)

Before World War II, most women representatives and senators gained their seats as widows appointed to complete their husbands’ terms. Some declined to leave when their “placeholder” term expired and then went on to win elections in their own right and continue their careers as legislators. In the cabinet, whose members are nominated by the president, things moved more slowly. But in 1933, Frances Perkins (1882–1965) became the first woman in a presidential cabinet when Franklin D. Roosevelt named her secretary of labor.

A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, Perkins lived in settlement houses, trained as a social worker, and worked as a consumer lobbyist. After witnessing New York’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, in which 146 workers—largely immigrant women and girls—died, she became a suffrage advocate and tackled issues surrounding labor, women, and children. In 1929, then-Governor Roosevelt named Perkins head of New York State’s Department of Labor; four years later, she would begin a stint as the longest-serving secretary of labor in history. Twenty years passed before a second woman was named a cabinet secretary, with Oveta Culp Hobby appointed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to head the newly formed Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. It took more than two decades longer for two or more women to serve in a cabinet at the same time.

In the postwar years, women increasingly ran for office rather than inheriting it, and the women of the Capitol grew in legislative experience and seniority. In the 1960s and 1970s, this core of women was joined by activists and politicians from the women’s and civil rights movements.

Representative Patsy Mink of Hawai‘i, the first woman of color elected to the House of Representatives, was the primary author of Title IX, which in 1972 amended the 1964 Civil Rights Act to include women. Following the example of the Congressional Black Caucus formed in 1971, women members of Congress elected from different parties and representing different constituencies and governing philosophies united in 1977 to form the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues to discuss topics of mutual interest.

Although more women are at the table, their numbers are still not equal to men’s. Doubtless, more women will follow the advice of Representative Shirley Chisholm: “If you wait for a man to give you a seat, you’ll never have one! If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring in a folding chair.” —E. Claire Jerry

and Lisa Kathleen Graddy

Read more in Smithsonian American Women, which is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Smithsonian American Women © 2019 by Smithsonian Institution

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.