Earlier this month, the Iraqi Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Antiquities and its State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, along with its partners, the Musée du Louvre, World Monuments Fund, ALIPH Foundation and Smithsonian Institution, officially announced the rehabilitation of the Mosul Cultural Museum.

As we, the representatives of the organizations, gathered together in the still damaged—but now recovering—second-largest city in Iraq, we not only marked the amazing progress in the effort but also presented plans for the 2026 reopening of its main building.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9a/26/9a2699f0-c319-4ada-8693-3f0f4d199155/7_plan_for_museum_rehabilitation.jpg)

Nine years ago, during its three-year reign of terror, the Islamic State extremist group, also known as ISIS or Daesh, severely damaged and vandalized the building.

The militant group’s 2014 assault on the museum stunned the world with its brutality. The group blew up an Assyrian throne base, leaving a gaping 18-foot-long hole in a gallery floor; jackhammered lamassu sculptures that had been excavated at nearby Nimrud; burned the library containing some 25,000 books and manuscripts; looted antiquities; and set fire to parts of the building.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/19/fd/19fda1d3-2afc-416c-9938-85c82727f5bd/4_hole_in_floor_assyrian_gallery.jpg)

It was heartening to be back in this ancient city that had been so physically devastated and socially traumatized. Many of the more than one million people who’d fled Mosul during the years of occupation had returned. Signs of life indicative of the typical vibrancy of the region abounded—from thriving commercial activity to lively street life and, yes, robust traffic and congestion.

Still there is much to do, especially in the Old City, where the terrorist group made its last stand in 2017. Work funded by the United Arab Emirates on the famed 12th-century al-Nuri Mosque and scaffolding for the reconstruction of its tragically leveled and nationally iconic al-Hadba minaret signal a city in recovery. A new bridge spanning the Tigris River joins the west and east sides of the city. ALIPH-funded projects, collectively known as the "Mosul Mosaic," include the rebuilding of the Mashki Gate at the ancient Assyrian site of Nineveh and the repair of the Dominican al-Saa’a, the Chaldean al-Tahera and the Syriac Orthodox Mar Toma churches; as well as the al-Raabiya and al-Masfi Umayyad mosques; and the Ottoman Tutunji House. These efforts speak not only to the bricks, but also to the mortar of the city's social life.

It is a grand effort that UNESCO calls “revive the spirit of Mosul”—an attempt to restore civility to a city that has long stood at the heart of Western civilization. The effort entails moving forward with a respect for the incredibly rich and layered past that has characterized the cultural and religious diversity of its people.

After allied forces retook the city, the Smithsonian worked closely with museum staff and cultural authorities to stabilize the Mosul Cultural Museum—fencing off the building; providing doors, locks and security; repairing windows and leaking skylights; and mitigating its flooded lower level.

The initial collaborative response was possible because of long-running Smithsonian and staff involvement with the Iraqi Institute for the Conservation of Antiquities and Heritage in nearby Erbil. Mosul Cultural Museum director Zaid Ghazi Saadallah was one of its first graduates. Numerous other staff had been trained in its various courses, resulting in close, trusted professional relationships and friendships.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/92/d7/92d77679-a66f-43fe-8a97-f21835242fe5/3_panel_for_announcement.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a9/7b/a97bd557-e84a-4975-9a09-c76b92c78d09/6_exhibition_on_museum.jpg)

The just-established international ALIPH Foundation, initiated by worldwide concern and spearheaded by France and the United Arab Emirates—and, for which I serve as a founding board member—made the restoration of the Mosul Cultural Museum its initial signature project in 2018.

It provided needed funds for the Smithsonian to obtain steel scaffolding to hold up the gallery floor, engage engineers in a structural assessment, build new storage and a conservation lab, and conduct a needs assessment. The Louvre joined in the assessment, concentrating on the museum’s collections and architectural history.

Smithsonian staff documented the ravaged museum and, as instructed by FBI experts, viewed the building as a crime scene, collecting forensic evidence of damage and looting. Louvre experts engaged in their own detective work, documenting the collection and the status of items that had been in the museum as well as those that had been returned to Baghdad years before the attack.

Based on the assessments and findings, ALIPH supported a second phase of the project, planning and preparing for recovery. The Smithsonian and the Louvre began initial staff training, while the latter took on the immense, time-consuming and challenging task of conserving and restoring surviving but severly damaged antiquities in the museum.

The World Monuments Fund, well experienced in the repair and reconstruction of historical and ancient sites in Iraq, joined as another major partner. In its view, the building, designed by the renowned Iraqi modernist architect Mohamed Makiya, was a marvel in joining contemporary sensibilities with historic Mesopotamian themes. World Monuments Fund staff along with a team drawn from the Arab world, the United States and Europe began the architectural, engineering and design studies that would be needed to rehabilitate the building and remake it into a modern museum. All the international partners worked closely with the Mosul Cultural Museum staff, as well as the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage and the local community, in developing those plans.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/3e/793eea67-f811-4f18-a85c-e8f69bce3cec/5_hatra_hall_workshop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/77/e3/77e397d7-c4cb-485f-9305-9a5cb838f4de/12_section_of_lion_of_nimrud.jpg)

To realize this vision, the ALIPH Foundation approved more than $12 million in additional grants—bringing its support to the Mosul Cultural Museum to over $16 million and leading to this month’s gathering and announcement.

The event was held in the museum’s damaged main building, in an open lecture hall that when I first visited had been flooded and full of refuse.

Iraqi Minister of Culture,Tourism and Antiquities Ahmed Fakak al-Badrani, himself a native Moslawi, addressed the overflowing audience of local civic and religious leaders, alongside Iraqi and international media, and noted the project’s symbolic importance for the city, the nation and the world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b0/b3/b0b36b11-436d-4555-8b10-da69ccf6588a/image-9.jpg)

Laith Hussein, the chairman of the State Board of Antiquities, lauded the role the museum would play in the education of future generations. An exhibition curated by Saadallah with Ariane Thomas, director of the Louvre's Ancient Near Eastern department, in the adjacent Royal Hall, the Mosul Cultural Museum’s original building, documents the origins, destruction and recovery of the institution.

Saadallah and World Monuments Fund leaders described how the architectural plan eliminates some of the add-ons and enclosures that followed after the original construction, and had darkened the interior and caused persistent drainage problems.

The plan provides greater access for those with limited mobility. In addition to its former halls, the museum now includes space for temporary exhibitions, including those highlighting ongoing archaeological work. The library will also be restored. To aid in its integration with the surrounding community, it includes a gathering hall for events, outdoor gardens and facilities, and a food concession.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1b/98/1b98b7bf-cb82-4145-a35c-ce4e53f95e94/image-830.jpg)

Poignantly, Saadallah noted, it will retain a portion of the gaping hole in the floor in the Assyrian gallery with its bomb-induced tangle of rebar—so that the memory of the terrorists' attempt to erase the history presented in the museum is not lost upon future generations.

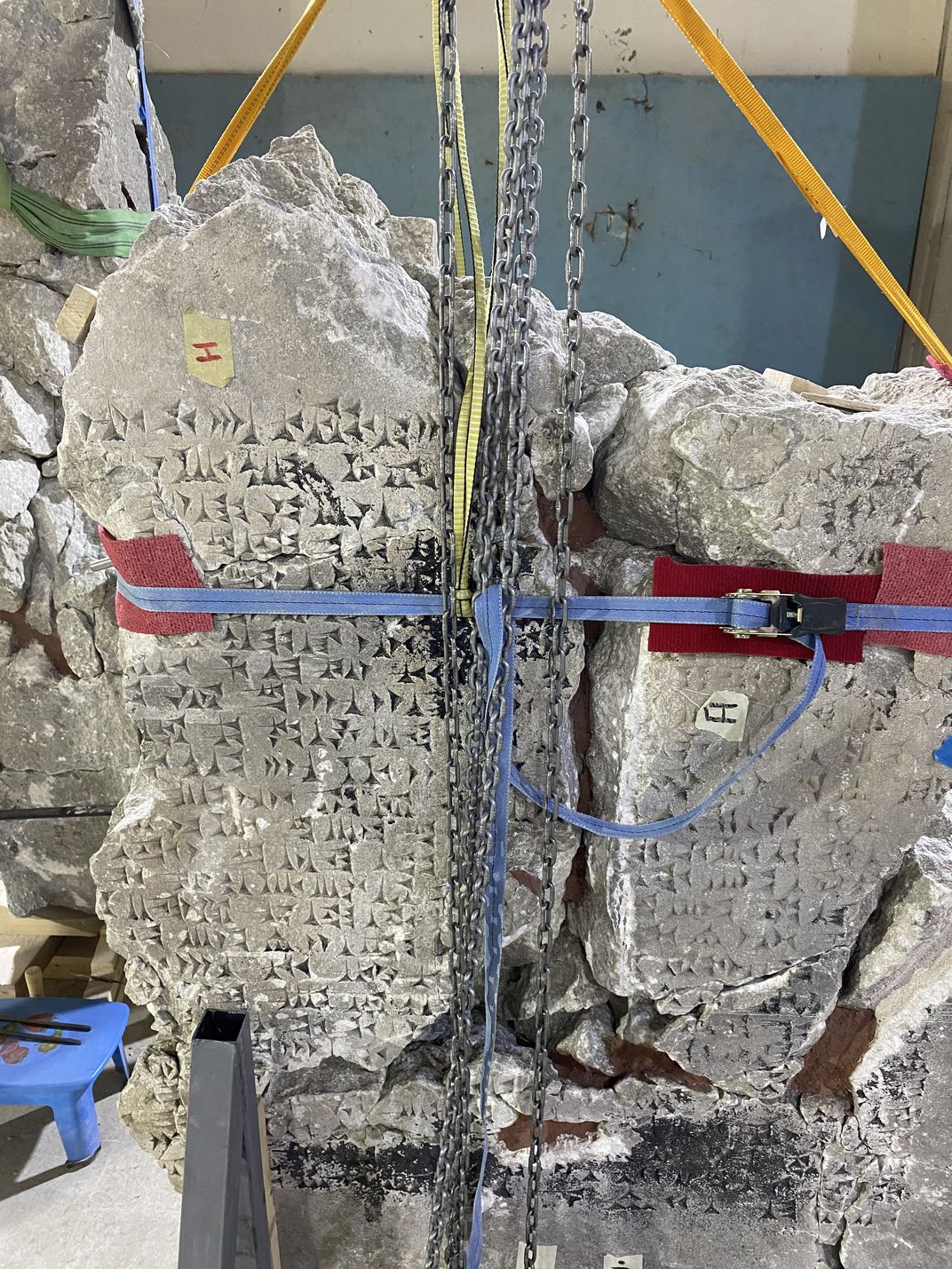

The Louvre will continue its work on the conservation and restoration of the collection. On display was evidence of the fine and exacting work accomplished to date that was led by the Louvre’s Daniel Ibled and the Mosul Cultural Museum team. Staffers are literally piecing together the remains of a royal dais, the lamassu, sculptures and stellae from thousands and thousands of fragmented pieces ranging from pebbles to multi-ton boulders. It’s like assembling several giant three-dimensional jigsaw puzzles.

As the World Monuments Fund begins work on the reconstruction and renovation of the building, the Louvre will work closely with the Mosul museum’s staff on the structure, content and design of exhibitions and their public presentation and interpretation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2a/c4/2ac479d0-34ec-4304-a6c2-3946fb53fbd4/11_lion_nimrud_restoration.jpg)

The Smithsonian, in consultation with the Louvre and the World Monuments Fund, plans a strategic capacity-building training program to foster the skillsets, abilities, and processes that the museum will need to survive and adapt to a fast-changing world. The training modules, will be delivered in person at the Iraqi Institute so that the staff develops their repertoire of knowledge and skills crucial for the operation of the museum. This will include everything from administrative and budgetary supervision to security and facilities maintenance, from collection management and conservation to visitor services and educational programs.

Summarizing the overall effort at the gathering, Valéry Freland, the ALIPH Foundation’s executive director, noted how the project has joined international and local partners working together to preserve the heritage of humanity and contribute to historical understanding and civic vitality—an appropriate response to the intolerance and brutality wrought by ISIS.

:focal(2016x1517:2017x1518)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/05/ce/05cee85a-2372-48a5-8c28-cea27b9bbfef/1_lead_lion_nimrud_cunneiform.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kurin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kurin.png)