The Smithsonian Institution is the world’s largest museum, education and research complex, and since its founding in 1846, it’s been a revered part of the American collective consciousness.

Yet perhaps because of its reputation, as well as the breadth and eclecticism of its collections—from the pen that signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to the R2-D2 costume from Return of the Jedi—people can arrive at the Smithsonian’s 21 museums and the National Zoo with more than a few misconceptions.

To celebrate the Smithsonian’s 178th birthday, let’s clear up a few of the myths, legends and misunderstandings surrounding the institution.

Myth #1: The Hope Diamond is cursed

Fact: It’s not cursed. Unfortunate events befell a few of its handlers.

Backstory: It’s true that some of the massive 45-carat diamond’s owners, like Marie Antoinette, met cruel fates. But the idea that the Hope Diamond was cursed became prominent only in the early 20th century as a marketing ploy devised by jeweler Pierre Cartier to entice Evalyn Walsh McLean, a Washington, D.C. socialite and the scion of a Colorado gold fortune, to buy the gem. Cartier promoted it not just as an object of beauty and geological rarity, but also as an infamous symbol of aristocracy and fate that would surely turn heads at any society ball. Any attention, he convinced McLean, was good attention.

With excessive media attention and a former secret service agent to protect the diamond, Cartier’s marketing ploy had worked perfectly. “Probably no jewel ever had a more sinister history than the Hope diamond dug out of India centuries ago,” the New York Times reported on January 28, 1911, when McLean purchased the jewel for $300,000 (almost $10 million today).

Tragedies later in McLean’s life—her husband ran off with another woman, her son was struck and killed by a car, and her daughter died of a drug overdose—contributed to the perception that the gem was cursed.

“But Mrs. McLean loved it,” her obituary in the Times read, “and ignored the dismal legends it reflected.”

After McLean’s death from pneumonia in 1947, jeweler Harry Winston bought her entire jewel collection and toured the Hope Diamond around the world before donating it to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in 1958.

If there really was a curse, the donation wouldn’t have broken it. The jewel was sent to the museum by registered mail and delivered by postal worker James Todd, who suffered several misfortunes the following year: a broken leg, the deaths of both his wife and dog, and the loss of his house in a fire. But Todd took it in stride. “If the hex is supposed to affect the owners,” he said, “then the public should be having the bad luck.”

Museum curators, however, dismiss the idea of a curse. The Hope Diamond is now the crown jewel of the museum's mineral and gem collection and has attracted millions of visitors to the Smithsonian over the past six decades.

Myth #2: The Smithsonian went in search of Noah’s Ark at Mount Ararat

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/36/a73605a5-268c-4677-9432-19548cec2ef7/gettyimages-1151390747.jpg)

Fact: The Smithsonian has never conducted archaeological work on Mount Ararat.

Backstory: According to the Book of Genesis, God became displeased with the wickedness of humanity and flooded the Earth. He told Noah to build an ark and fill it with two of every animal so that they might replenish the world.

After the flood, the world dried up. “And the ark rested in the seventh month, on the seventeenth day of the month, upon the mountains of Ararat,” the Scripture reads.

For those who take the Bible as a historical record, the hunt for remains of Noah’s Ark has led to the modern-day Mount Ararat in Turkey. Over the years, bits of speculative evidence have popped up and kept the archaeological search going. Confidential satellite images taken of the mountain by the U.S. Air Force during the Cold War, for instance, showed a strange “Ararat anomaly” that some took as evidence of the ark, but the government maintains that the ark has never been seen in a photograph.

In fact, there is no definitive proof that the ark existed at all, let alone that it came to rest on Mount Ararat. Some scholars speculate that the “Ararat” in Genesis might refer to the region more widely, or that, if there was a flood, it would have been confined to the Mesopotamian plain.

Regardless, the Smithsonian has not gone looking for the ark.

Myth #3: The Smithsonian rejected a Barbie doll head that an amateur paleontologist claimed was a prehistoric skull

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/29/c229aee7-ca21-4031-99e6-bff465243d42/gettyimages-696652.jpg)

Fact: The purported rejection letter from the Smithsonian was a viral gag. The submission never took place.

Backstory: The myth goes something like this: In 1994, Harvey Rowe, a curator of antiquities at the Smithsonian, sent a letter in response to a submission of a purported prehistoric human skull that an amateur paleontologist had found in his backyard.

“Thank you for your latest submission to the Institute, labeled ‘211-D, layer seven, next to the clothesline post. Hominid skull,’” Rowe’s letter began.

“We have given this specimen a careful and detailed examination, and regret to inform you that we disagree with your theory that it represents ‘conclusive proof of the presence of Early Man in Charleston County two million years ago.’ Rather, it appears that what you have found is the head of a Barbie doll, of the variety one of our staff, who has small children, believes to be the ‘Malibu Barbie,’” the letter said.

The letter spread across the internet. But the problem was, none of it was true.

No one submitted a Barbie’s head thinking it was an early human skull, the Smithsonian does not have an antiquities department, and the real Harvey Rowe was just a bored graduate student who wrote the parody letter and circulated it among his friends before it blew up online.

Myth #4: The Smithsonian discovered Egyptian ruins in the Grand Canyon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/49/9249dfda-fcb5-4cd9-b94f-38187154ec87/gettyimages-2159247.jpg)

Fact: It didn’t. The report was only made by one newspaper but continues to run amok.

Backstory: On April 5, 1909, the Arizona Gazette ran an article with the headline: “Explorations in Grand Canyon: Mysteries of Immense Rich Cavern Being Brought to Light... Remarkable Finds Indicate Ancient People Migrated from Orient.”

The Gazette reported that explorer G. E. Kinkaid discovered a “great underground citadel” as they floated down the Grand Canyon in a wooden boat.

“The archeologists of the Smithsonian Institute, which is financing the expeditions, have made discoveries which almost conclusively prove that the race which inhabited this mysterious cavern, hewn in solid rock by human hands, was of oriental origin, possibly from Egypt, tracing back to Ramses,” the article said.

“If their theories are borne out by the translation of the tablets engraved with hieroglyphics.… Egypt and the Nile, and Arizona and the Colorado will be linked by a historical chain running back to ages which staggers the wildest fancy of the fictionist,” the Gazette concluded.

The Smithsonian, however, has no record of any such expeditions, and it’s doubtful that Kinkaid existed.

Whether the source “bamboozled the Gazette or if the Gazette bamboozled its readers isn't quite clear,” a columnist for the Arizona Republic wrote in 2008 when a reader sent in a question about the myth.

“However,” the columnist continued, “it is safe to say the whole thing was a hoax.”

Myth #5: Betsy Ross stitched the Star-Spangled Banner kept in the Smithsonian’s collections

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mary-Pickersgill-3.jpg)

Fact: Actually, Mary Pickersgill stitched the flag that inspired the national anthem, in 1813.

Backstory: The first standard of the United States is popularly attributed to Betsy Ross, a professional flag maker who has become a national folk hero. The legend stems from Ross’ grandson William J. Canby, who, in 1870, retold a story that a relative had told him in 1857, well after Ross’ death in 1836.

According to the Ross family account, which Canby popularized at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, George Washington approached Ross in the spring of 1776 with a rough sketch of a flag and asked her to make a national standard. Washington suggested a six-pointed star, but Ross preferred one with five. Washington agreed, and the flag design was born.

Canby’s story about the creation of the national flag captured imaginations. But no documentation links Ross with making the first flag, and the events described in Canby’s account take place a year before the passage of the Flag Act, the legislation that dictates the style and substance of the national flag.

Visitors to the National Museum of American History sometimes ask if the Star-Spangled Banner—currently on display after extensive conservation efforts—is an example of Ross’ work. That massive flag was stitched by Mary Pickersgill (with help from her family and community members) and flew over Fort McHenry during the 1814 Battle of Baltimore, inspiring Francis Scott Key to pen the poem that became our national anthem.

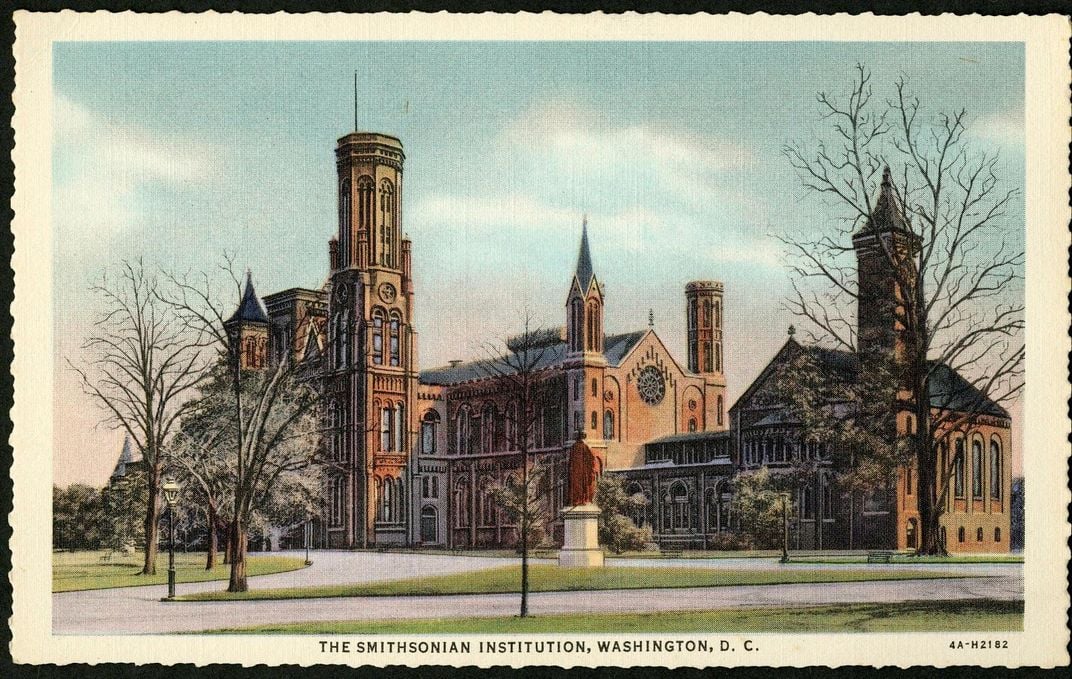

Myth #6: The Smithsonian Castle is haunted

Fact: No ghosts have been detected. The only souls who have haunted the Castle are tourists searching for food and information.

Backstory: Tales of otherworldly inhabitants stalking the Smithsonian’s hallowed halls have been floating around for over a century. The Institution’s founder, James Smithson, is said to be among these otherworldly visitors, but he never even visited the United States. Another rumored ethereal presence is paleontologist Fielding B. Meek, who lived in pitifully small rooms in the Castle with his cat in lieu of a salary. His first residence was under one of the Castle’s staircases before an 1865 fire forced him to move to one of the towers, where he died in 1876.

“Many ghost stories have swirled about,” says the curator of the Castle collection Richard Stamm, “but in the many years I have been in this building, no ghosts have ever shown their faces to me!”

That is expected to continue when the Castle reopens to the public after renovations in a few years.

Myth #7: The Smithsonian owns a Very Specific Body Part belonging to John Dillinger

Fact: The Smithsonian does not own any part of the infamous bank robber’s corpse.

Backstory: Some say that a morgue photograph of John Dillinger's sheet-shrouded corpse suggests that nature was rather generous to the gangster. A popular rumor arose asserting that his organ was preserved in the collections of the Smithsonian.

This myth proved so pervasive that the Smithsonian once had a form letter to respond to queries: “In response to your recent query, we can assure you that anatomical specimens of John Dillinger are not, and never have been, in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution.”

Myth #8: The Smithsonian has an archive center underneath the National Mall

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/1f/f11fedf4-7e53-48d7-8bc9-17119aef6300/gettyimages-564109375.jpg)

Fact: The Smithsonian’s storage facilities are mostly located in Suitland, Maryland.

Backstory: The notion that a labyrinthine network of storage space exists beneath the Smithsonian museums on the National Mall may have started with Gore Vidal’s 1998 novel The Smithsonian Institution, in which a 13-year-old genius is beckoned to help build the atomic bomb in the basement of the Smithsonian. On his absurd adventure, which the New York Times called a “strange confection of science fiction, historical costume romance, political satire and veiled autobiography,” the fictional protagonist meets Abraham Lincoln, J. Robert Oppenheimer and other long-dead historical figures in the basement.

This type of story was more recently popularized by the 2009 movie Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian, where historical figures immortalized by the museum’s collections come alive again to help a hapless security guard.

No such storage facility is to be found. The archive center depicted in the film is based on the Smithsonian’s Maryland storage facilities.

An underground complex of passageways connecting the Freer, the Sackler, the Castle, the African Art Museum and the Arts and Industries Building is staff only.

There is also a tunnel that connects the Castle with the National Museum of Natural History. While it’s technically large enough to walk through, a person has to contend with cramped spaces, rats and roaches. Most employees prefer a quick jaunt across the National Mall.

Myth #9: The Smithsonian collected a steam engine that was lost on the Titanic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Titanic-4.jpg)

Fact: There is no such steam engine in the museum’s collections, and the Smithsonian will not acquire or display artifacts culled from the Titanic wreck site.

Backstory: Inventor Hiram Maxim—who developed technology such as the machine gun and the mousetrap—supposedly donated a steam engine used in a failed flying machine to the Smithsonian. The equipment was allegedly shipped from Britain to the United States aboard the ill-fated RMS Titanic. However, the ship’s cargo list, full of fancy foodstuffs and spirits, what the New York Times calls “high-class package freight,” does not include any records of shipments made by Hiram Maxim.

When it comes to the Titanic, the Smithsonian treats the site of the wreck as a memorial to those who perished. Only Titanic artifacts retrieved from the surface of the North Atlantic, like pieces of mail, have ever been on view from the collections of the Smithsonian.

Myth #10: James Smithson’s remains are housed in the Castle's sarcophagus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/ae/53ae56d2-bbad-41e2-8af0-171d7ffc56fb/gettyimages-1052797980.jpg)

Fact: The sarcophagus is just symbolic. The body of the Institution’s founder resides in the red Tennessee marble pedestal underneath.

Backstory: James Smithson, a nomadic British scientist who never set foot on American soil, died in Italy in 1829. While his fortune went to establish the Smithsonian Institution in the United States, his remains were initially interred in the British San Benigno cemetery outside of Genoa and his gravesite was marked with an elaborate sarcophagus.

In 1903, the cemetery was supposed to be moved to make room for a nearby quarry. The Smithsonian took the opportunity to bring the body of its namesake to the U.S. for the first time. Alexander Graham Bell, a regent of the Smithsonian, personally traveled to Genoa to exhume Smithson’s remains and accompany the benefactor back to the U.S.

Smithson now rests in a crypt in the Smithsonian Castle, where his body has stayed—except for one occasion in 1973.

James Goode, former curator of the Castle, claimed that he disinterred Smithson’s body because of ghost sightings. Officially, however, the reasons were more scientific: to mount a complete study of the coffin and the skeleton itself. A copy of the examination of the bones by the Smithsonian’s physical anthropologist Larry Angel was filed inside the coffin before it was sealed and returned to the crypt.

Myth #11: The Smithsonian hid evidence of giant humans

Fact: This myth was created by an online satirical newspaper. The evidence never existed and, even if it did, the Smithsonian is not in the business of destroying artifacts.

Backstory: In 2014, a website called World News Daily Report claimed that a group called the American Institution of Alternative Archaeology (AIAA) blamed the Smithsonian Institution for destroying evidence of prehistoric human skeletons up to 12 feet tall.

The AIAA alleged that the Smithsonian was intent on supporting the theory of evolution and willfully ignoring evidence of a massive race of human ancestors that roamed the Earth.

The Smithsonian, according to World News Daily Report, then sued the AIAA for defamation, resulting in a Supreme Court trial in which multiple whistleblowers confirmed AIAA’s allegations.

The World News Daily Report claimed that one curator who was on his deathbed wrote: “It is a terrible thing that is being done to the American people. We are hiding the truth about the forefathers of humanity, our ancestors, the giants who roamed the earth as recalled in the Bible and ancient texts of the world.”

This fanciful account never had a shred of truth to it. The AIAA does not exist, there was never any evidence of biblical giants in North America that the Smithsonian could conceal and, of course, no such case was ever brought to the Supreme Court.

In fact, World News Daily Report, which is now defunct, was a self-described “news and political satire web publication, which may or may not use real names, often in semi-real or mostly fictitious ways. All news articles contained within worldnewsdailyreport.com are fiction, and presumably fake news.”

Myth #12: The Smithsonian collects and preserves individual snowflakes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ef/44/ef44ac0d-452c-4848-8781-40f50c03057a/sia-sia2013-09132.jpg)

Fact: While the Smithsonian doesn’t keep a freezer full of snowflakes in its collections, it does have prints of incredibly detailed photographs of snowflakes from the early 1900s.

Backstory: Wilson “Snowflake” Bentley of Vermont was the first person to perfect photographing snowflakes, allowing them to drift carefully onto black velvet underneath a microscope and his camera lens.

In 1903, he sent 500 prints of his snowflakes, each in their unique, delicate crystalline form, to the Smithsonian to witness the beauty of the natural world for posterity. Many of the photos are available online.

Myth #13: The Smithsonian preserves every single tweet

Fact: Not us! The Library of Congress used to, however.

Backstory: In 2010, the Library of Congress announced that it was acquiring all public posts on Twitter (the social media site now known as X) from 2006 to 2010 and going forward. A few years later, the Library said that it would only be archiving tweets on a “selective basis.” The ambitious project ended just as it began: without the Smithsonian’s involvement.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/23/6b23bac3-2fdf-4770-850d-ae6c10440d27/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/44/d0/44d08fb6-5372-4387-865b-98d29b30ca5a/social-media-dimensions.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eli2.png)