Chris Strachwitz did not think of himself as a record producer, but a song-catcher. He belongs firmly in the tradition of Cecil Sharp, the British musicologist who collected hundreds of Elizabethan folk songs during World War I in the West Virginia hills. He is the modern descendant of John and Alan Lomax, the intrepid pioneers who made field recordings of Lead Belly, Woody Guthrie and dozens of others for the Library of Congress. He entered the record business as a means to support his passion; he only made money by accident. San Francisco Chronicle jazz and pop critic Ralph J. Gleason told Strachwitz that he didn’t have a record company—he had a hobby. He frequently found himself in confounding and complicated circumstances when it came to making his records with these remarkable musicians.

In the course of more than 40 years behind the one-man operation, Strachwitz became the single most important and formidable folklorist of his generation. He not only brought to light important American blues musicians such as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Mance Lipscomb and zydeco king Clifton Chenier, but he also single-handedly rescued the vast and rich legacy of Texas-Mexican norteño music, even though he barely spoke a word of Spanish. He recorded blues in Chicago, Cajun music in the Louisiana bayous, bluegrass in Appalachia, Mexican music in Texas barrios. He retrieved hundreds of important forgotten records from the past and restored them to the literature. There has not been a single corner of the sweeping panorama of American music he did not explore or an important trend or discovery in American vernacular music over the past 50 years that does not bear his fingerprints.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3d/85/3d854df0-ab99-4b97-9c0d-0f9e641ebc3a/64-65_lightninhopkins_lcwilliams.jpg)

Strachwitz died this May, at the age of 91, but seven years ago, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings acquired Arhoolie Records, the small independent record label he founded in 1960, from him. Since then, Folkways has made all 350 albums from the collection—“a national treasure of recorded music,” according to Daniel Sheehy, then the director of Folkways—available to the public on CD and digital formats.

Strachwitz made records like a documentary filmmaker: crisp, dry recordings designed to feature the performance and the repertoire. He never washed his tracks in reverb or other effects. He didn’t spend infinite hours performing intricate, detailed mixes. He didn’t bring arrangers, sidemen or other professional assistance into making his records. He was producing aural documents of the music, and the more real it sounded, the better. Because of this, his records stand up through the years; they sound as fresh and vital as the day they were first captured.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/46/dc/46dcb4a4-f545-4d32-9d98-00c0ce44e284/72-73_hodges_brothers_mississippi.jpg)

All through his adventures in recording this music, Strachwitz also brought a camera. As he didn’t think of himself as a record producer, neither did he consider himself a photographer. He brought the used Leica 35 mm camera he bought in Germany when he was in the Army in the early 1950s to take snapshots. To him, the camera was nothing more than a utilitarian tool to make album cover photos and perhaps portraits for publicity. As with his records, his simple intent belied the skill and keen perspective Strachwitz brought to his photography. Because of his intimate knowledge of his subjects and their culture, he knew what to shoot. He knew how to pose the people, what to include in the composition and how to tell their story in a single frame. As with his records, his photographs document an incredible journey through American music from his special vantage point with his knowing eye.

He was born July 1, 1931 as Christian Alexander Maria, Graf Strachwitz von Groß-Zauche und Camminetz, in Gross Reichenau, Lower Silesia, then within Germany and now known as Bogaczow, Poland. His family were aristocratic farm owners, although his grandmother had been born in San Francisco, daughter of U.S. Senator Francis Newlands of Nevada. Count Strachwitz never used his title. “Over here,” he said in an interview, “it doesn’t count.”

Young Strachwitz’s lifelong fascination with records began with a record the family owned of a song from an old operetta, “Die Berliner Luft” (The Berlin Air). He listened to it repeatedly until his father warned him not to play the record. The songwriter was Jewish, he told the 10-year-old boy, and the Nazis might not like it. Strachwitz learned early on that listening to music was not necessarily an innocent pleasure, but he never lost his fascination with records.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/73/5e/735ed5c5-e3c3-4534-a18d-9a0a8cab3c4d/92-93_rev_overstreet_phoenix.jpg)

After the war and two years at an uncle’s house in the British zone, his family was invited to immigrate to the U.S. by two great-aunts, one of whom offered her large home in Reno, Nevada. The 16-year-old was sent to boarding school. Strachwitz first encountered the many sounds of American music on late-night radio. The laments of hillbilly singers and bluesmen resonated with the shy, young immigrant who felt like a stranger in strange land and related to the outsider appeal of these rural musicians, who clearly took no part in mainstream American life.

His musical education continued as he attended the exclusive Cate School in Southern California, where the movie New Orleans with Louis Armstrong, the full Kid Ory band and Billie Holiday made a big impression on the gawky, awkward teen in 1951. He started collecting records. In 1952, he first heard the traditional New Orleans jazz master George Lewis and his Black band on a daylong Dixieland jamboree at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, on a bill with a batch of square bands playing what Strachwitz would come to call “Mickey Mouse music,” but George Lewis was the real deal. The clarinet player whose career went back to the 1920s was a leading figure in the ongoing New Orleans jazz revival at the time, an authentic link to the music’s storied past.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/71/fc/71fc5ae0-515d-4bb3-9746-e129abdd4cae/128-129_sonny_boy_williams_arkansas.jpg)

While attending Pomona College, Strachwitz schooled himself on the radio in the rich variety of American music on the margins of society—country, jazz, gospel and blues. He first heard Texas bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins on Hunter Hancock’s Harlem Matinee on Los Angeles radio, and the grizzled, ageless voice of the singer enraptured Strachwitz. He quickly became Strachwitz’s favorite blues singer and a touchstone for everything that would follow.

Strachwitz visited Dolphin’s of Hollywood, a 24-hour, 7-day-a-week record store in the heart of South Central Los Angeles that served as much as a cultural center to the Black community as a music store. They did not see that many white customers, and when Strachwitz asked if they had anything by Lightnin’ Hopkins, the sales lady went into shock. “You like those down home blues?” she said.

After finishing college, two years in the Army and earning credentials at the University of California, Berkeley, Strachwitz was teaching German in a public school in Los Gatos, a small town amid fruit orchards an hour’s drive south of San Francisco, when he received the postcard that would change his life.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/77/a2/77a2b36d-6b9e-45ff-a04f-918ed6605a48/165_buddyguy_bonnieraitt.jpg)

The world of blues enthusiasts was quite small at the time, and Strachwitz had met fellow blues scholar Sam Charters in Berkeley some years before when Charters was working on the first book on the subject, “The Country Blues.” On the postcard, Charters wrote that he had located the elusive blues singer Lightnin’ Hopkins in Houston. Hopkins, whose recording career had cooled considerably, was a mysterious figure to these arcane record collectors, who knew little of his background, even where he lived. To Strachwitz, this was monumental news that would prove to be life-changing. In summer 1959, as soon as school let out, the 28-year-old public school teacher high-tailed it to Texas to see bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins.

That rainy night in Houston, on a trip he would later describe as “a pilgrimage,” Strachwitz first heard Hopkins in a low-rent Third Ward beer joint called Pop’s Place. The legendary bluesman ad-libbed his way through a recitation of the evening’s difficulties—bad weather, car trouble on the way to the club, aches in his joints—winding up by noting “and this man come all the way from California just to hear po’ Lightnin’ play.” This was Strachwitz’s road to Damascus moment. His life would never be the same.

For the next 30 years or so, Strachwitz would document his travels with a tape recorder and camera. As he assembled his vast library of field and studio recordings of American musicians, he collected a reservoir of photographs along the way that unwittingly chronicled his deep journey into the heart of American music. It all began with his fascination with Lightnin’ Hopkins.

Hopkins, Lipscomb, Chenier, McDowell—they’re all gone now. There won’t be any more like them; the model is discontinued. These rare birds were sighted by Strachwitz when many other people weren’t even looking, and they laid down bedrock literature of American folklore. It turned out to be the last chance to capture these sounds, and Strachwitz was out there, largely by himself, collecting their stories, catching their songs, taking their pictures. He alone was Arhoolie, chief cook and bottle-washer, and he never had to answer to anyone else, and he never did a thing to make his records sell one extra copy. He made the records for himself, and, although the music belonged to the musicians, the vision was Strachwitz’s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fb/12/fb12bf10-a482-4477-af76-1f0e2a352538/189_flaco_jimenez_les_blank.jpg)

Strachwitz went straight for the heart of American music. His unerring instinct for the genuine served him throughout his mission. He despised artifice and once chastised the formidable bluesman Howlin’ Wolf for rolling around on the stage and engaging in bullshit. “Yeah,” Wolf told him, “but people love bullshit.” Not Strachwitz. He wanted to feel a musician’s soul in his music, not marvel at contrivance or technical ability. He wanted truth and guts, not entertainment. If a musician couldn’t connect to him on a visceral level, Strachwitz wasn’t interested. Pop music, pointless and puerile, was beneath his contempt.

With those criteria, he sought out musicians who had been cast aside, both by the commercial music industry, who used them and disposed of them, and the community that surrounded them, as it moved away from regional culture. Mass media and corporate marketing spelled an end to regionalism, creating an artificial culture that can be mass-produced and mass-marketed. Strachwitz watched that disintegrate, first with the blues and old-time country music, and then with the Tex-Mex music, as it became infected with hip-hop and modern dance beats. For much of the music he chronicled, if Strachwitz hadn’t been there, it would be like it never was.

The days of Strachwitz climbing over back fences to find some forgotten blues genius are long over. In many ways, he was like a cowboy who rode the range contending with the coming of the automobile and his own obsolescence. He never stopped making records until Arhoolie was sold and then given to the Smithsonian Institution in 2016. He never stopped taking photographs, although as the digital era dawned, he moved from black-and-white to color photography and, eventually, videos. The most amazing thing about him—and there are so many—is that Strachwitz never lost his enthusiasm, never lost track of his bliss, and was always out there looking for the next big thrill. The lonely German kid who found such indescribable pleasure in old American records was always alive inside of him.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/80/8f80afe1-be18-4c14-8809-5be90595bb85/216_losalegres_deteran.jpg)

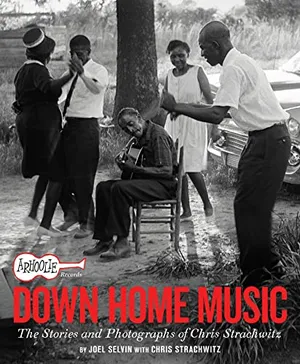

Arhoolie Records Down Home Music: The Stories and Photographs of Chris Strachwitz

A visual storytelling celebration of American roots music in its rich variety through unseen and newly scanned photographs by the founder of the legendary Arhoolie Records.

Strachwitz went looking for the real America. The people on his recordings sing this country’s history. Their stories are the story of this country, all the joy and heartbreak, all the vaunted hope and dismal reality. It is all there in the music he collected, the songs he caught, the photographs he took—a portrait of America as rich, detailed and truthful as any.

As much as the future cannot be known, the past is always with us. Strachwitz reached into a disappearing past and, before it was gone, took these pictures and made these records. In doing so, he preserved a way of life full of wisdom and hope for the future. Since he always approached these tasks with a guiding intellectual curiosity and a scholarly bent, the result was a well-organized inquiry into American music and the country that made the music. As much as coincidence and good luck played their part, Strachwitz compiling this body of work that encompassed the far reaches of the field was no accident, but the product of a well-defined, brilliantly executed pathway.

All those thousands of miles behind the wheel of his car in pursuit of his vision showed Strachwitz an America nobody else saw. As the scrub trees and endless shrubbery of the Mississippi wilderness whizzed past his car window, the radio blasting some crazy preacher or mariachi music, he picked up the last vestiges of the old ways.

The world caught up with Strachwitz and the music he collected. Today, there is a drive to put up a statue of Clifton Chenier in Opelousas, Louisiana. Lightnin’ Hopkins is revered around the world as one of the last great bluesmen. Flaco Jiménez is viewed as a national treasure in Texas, and there is a statue of him in San Antonio. The folk music Strachwitz celebrated has been spread in movie soundtracks, in television commercials and at every end of society as music suffused the culture at the close of the 20th century. In a computer-driven digital age, the appreciation of handmade, homegrown music has only increased.

As corporate record executives make room for the music, they keep trying to find a category that works, a box to contain the uncontainable. They call it “Americana” or “roots music.” Some call it “acoustic music,” which is hilarious—isn’t all music acoustic? Strachwitz was never in doubt. He always knew what it was—down home music.

From Arhoolie Records Down Home Music: The Stories and Photographs of Chris Strachwitz by Joel Selvin with Chris Strachwitz, published by Chronicle Books

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1000x667:1001x668)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/9d/6b9d2f76-1bb7-4d86-bb89-13180e7c2c57/138-139-fred_mcdowell.jpg)