How John Coltrane’s ‘My Favorite Things’ Changed American Music

Looking back at the moment when one of our greatest jazzmen raised the stakes for everyone who came after

:focal(1135x1130:1136x1131)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/90/fd/90fd5292-b38c-488c-9901-cb7ff3494570/janfeb2024_g12_prologue.jpg)

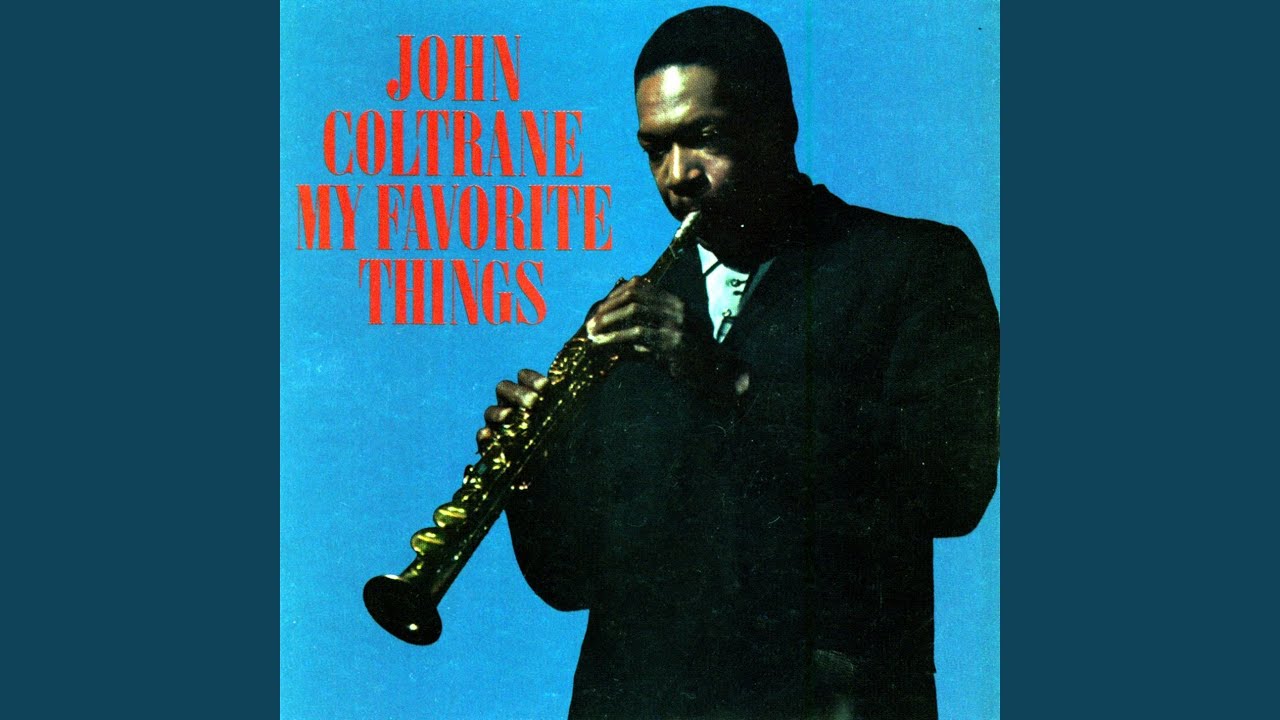

They gathered one afternoon in late October of 1960, at the Atlantic Records studios in a nondescript building at 234 West 56th Street in New York: pianist McCoy Tyner, just 21, a prodigy from Philadelphia; Steve Davis, upright bass, 31, also from Philly; and Elvin Jones, at 33 a veteran drummer who had played with everyone from Art Farmer and Pepper Adams to Gil Evans and Miles Davis.

And then there was John Coltrane, 34, already widely acknowledged as the next great jazz saxophonist, following Charlie Parker’s death in 1955. The little band had been playing together since May.

It was the first proper recording session for the John Coltrane Quartet—and it promptly produced one of the greatest moments in jazz history: Coltrane’s rendition of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things.” A regular had recently shown Coltrane the sheet music one night at the Jazz Gallery, a club on St. Mark’s Place in the East Village, and Coltrane thought he could make something of it.

“We took it to rehearsal and, just like that, fell right into it,” Coltrane said in a 1961 interview.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/74/80/7480c46e-a8eb-44f5-994e-e908add54071/janfeb2024_g14_prologue.jpg)

It was also a pivotal moment in Coltrane’s career and in his artistry, a tipping point of technique and inspiration, of practice and poetry, of his widening understanding of himself and his place in things. In that single landmark recording, you can feel Coltrane fully embrace the entirety of his promise, not only as a saxophonist, but also as a bandleader, composer and arranger. And maybe as a man.

Until that day, Coltrane had been the overachieving sideman, playing someone else’s music in someone else’s band. He was the best tenor player of his day but was almost always standing in the long, cool shadow of lead trumpet players like Dizzy Gillespie or Miles Davis, both of whom eventually fired Coltrane for his unreliability and drug use. (Davis had the uncanny grace, patience and good luck to hire him back after he got clean.)

But once Coltrane kicked heroin in 1957, he imagined a new sound for himself and found new determination to create the music only he heard. Like every true prophet, Coltrane had wandered but was not lost.

“The Coltrane who’s a sideman for Miles Davis is playing a completely different kind of music in a very different way,” says Steven Lewis, curator of music and performing arts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “And then what you see is this creative explosion once he’s running his own band.”

And “My Favorite Things,” from its opening cymbal crash, was the first, undeniable blast.

Coltrane was born in Hamlet, North Carolina, in 1926. He was an only child. His father and his grandfather were both preachers, and you can sometimes hear the gospel-style call-and-response cadence in his playing. When Coltrane was 12, those two men died within weeks of each other. He was cut adrift by the loss, but he was just starting on the sax that year—and his music saved him. He clung to that horn. He and his mother moved up to Philadelphia, where he studied at the Granoff School of Music. He played the alto sax all through his stint in the Navy, in 1945 and 1946. Eventually, you hear in the earliest Coltrane recordings from the late 1940s his clumsy devotion to both Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker. Genius came later.

Like Parker, he got hooked on heroin. Unlike Parker, he found God and got clean before it killed him. All at once, his sound was different. Stronger. Deeper. Filled with new energy and breath and purpose. He had always practiced obsessively, experimenting with dozens of mouthpieces and reeds, never quite finding whatever sound he heard in his head. Then came that afternoon on 56th Street, when Coltrane arrived at an otherworldly sound all his own.

As a point of reference, the year Coltrane recorded “My Favorite Things,” the No. 1 Billboard hit was the Percy Faith Orchestra playing the “Theme From a Summer Place,” a piece of movie music so anesthetic you could pipe it straight into any operating room in the world.

“My Favorite Things” was just as recognizable as any other Billboard hit—one of the most beloved songs from one of the most beloved musicals in history, The Sound of Music. But unlike the early rock or novelty pop songs that charted in that era, it’s also a song of deceptive complication, a bittersweet showtune pivoting between major and minor, from dark to bright, lighting Coltrane’s way to something utterly new.

The original is a midtempo waltz about finding joy in the ordinary, first sung on Broadway by Mary Martin a year before Coltrane’s historic Atlantic sessions. On the cast recording, it takes Martin and Patricia Neway 2 minutes and 45 seconds to sing it.

Coltrane’s version, by contrast, is a hypnotic, nearly 14-minute-long whirling dervish of a thing, vamping an E minor into E major again and again and again, chanting and droning, propelled by Tyner’s insistent, percussive left hand on the keys. Davis on his bass way down low; Jones up high, on top of that cymbal.

Those 14 minutes changed everything. The album on which they appeared was a remarkable artistic and commercial success—50,000 copies were sold in 1961, landmark numbers for a jazz LP. That success quieted, without quite silencing, critics who had lately been complaining about the wearying length of Coltrane’s solo improvisations. At the same time, the My Favorite Things LP brought jazz to new audiences, helped along by radio DJs who made a hit of the shortened 45-rpm version of the single. And it made John Coltrane a star.

Perhaps surprisingly, given its chordal simplicity, Coltrane’s rendition of “My Favorite Things” helped to inspire lengthier jams in the jazz world, and later among psychedelic rock groups in the late 1960s. In his 2005 memoir, Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead recalled urging his band mates “to listen closely to the music of John Coltrane, especially his classic quartet, in which the band would take fairly simple structures (‘My Favorite Things,’ for example) and extend them far beyond their original length with fantastical variations, frequently based on only one chord.”

Many have recorded “My Favorite Things,” from Mary Martin to Julie Andrews to the Supremes to Bobby McFerrin to Kelly Clarkson. But only Coltrane carries the song so far and into such mystical territory. It’s not a different version so much as a message from a parallel universe.

Coltrane the compulsive seeker was never quite satisfied with his own sound. “Between what I think and what you hear,” Coltrane said to French concert producer Frank Ténot that day in the studio, indicating his sax, “there’s this damned instrument.”

Still, Coltrane loved performing the song and never lost his knack for summoning the majesty of the original recording, sometimes even transcending it: The 1963 live recording of Coltrane playing “My Favorite Things” at the Newport Jazz Festival may be the best jazz recording ever made.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/66/b1662894-1f0c-4c37-a5e1-3bcfea9a963c/janfeb2024_g13_prologue.jpg)

In Coltrane’s hands the song becomes an epic of cultures and history, of pain and loss and catastrophe, of optimism and hope, of our disparate roots and the tangle of our histories, of musical forms from the Bay of Bengal to the Alps to North Africa to the American South, somehow synthesized into something like Afrofuturism. A singular, harmonious and unmistakably American piece of art, filled with life and the lilting promise of something like heaven.

John Coltrane died of liver cancer in 1967. He was 40. Yet for many of us he lives on, and in San Francisco, he has been canonized as the patron saint of the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church.

At the end of things there’s only you and John Coltrane, together across time in the music. Go to Long Island to say goodbye, to Dix Hills, where he lived in a modest brick house on the edge of the suburban woods with his second wife, Alice.

At Pinelawn Memorial Park, 40 miles and a world away from New York City’s recording studios and nightclubs, the two are buried in the shade of a big white oak. In summer the cemetery smells of cut grass under a high sun, and the leaves of that big tree whisper in the stillness.

I heard Coltrane’s version of “My Favorite Things” before I ever saw Julie Andrews sing the song in the 1965 movie. I was an only child prone to loneliness and melancholy. While there was nothing very special about my family’s unhappiness, growing up I spent long hours lying on the floor among scattered album covers in front of our old Magnasonic 210, listening to Coltrane play “My Favorite Things” with my ear to the speaker. At 7 or 8 I was already spellbound. It was to me then and now at once strange and soothing, alien yet as familiar as the thread of my own pulse. It gathered me up and held me, and I was safe inside it.

If the Broadway original was the candied antidote to simple sadness, to dog bites and bee stings, Coltrane’s version of “My Favorite Things” somehow consecrates love itself as an absolute and universal joy.

But it is impossible to write about music.

Say instead: A long time ago music saved John Coltrane. Then John Coltrane saved me. He saves me still.

The Key to Spirituality

A church in San Francisco gives new meaning to the term “gospel music”

By Brandon Tensley

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d8/6f/d86fa0b3-92e7-45d0-af51-6f4cace271ff/coltrane_icon.jpg)

Beyond his pathbreaking musical accomplishments, John Coltrane might be the most spiritually divine jazzman in history. At least, that’s what congregants think at the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church in San Francisco.

The church was established by two young lovers, Franzo and Marina King. While celebrating their first wedding anniversary in 1965, the couple went to a show at the Jazz Workshop, a beloved San Francisco nightclub. When Coltrane began to play, the Kings say, the performance felt like a message from God—almost a baptism by sound. The couple became convinced that Coltrane’s art was a path toward spiritual enlightenment. By 1969—two years after Coltrane’s death—they’d established the church at 1529 Galvez Avenue in San Francisco, and that same year, Franzo became a bishop in the Church of God in Christ.

For congregants, the holy text is not the Bible, but rather A Love Supreme, Coltrane’s 1965 album, considered by some to be his masterwork, which includes audio of Coltrane intoning a prayer. On the first Sunday of every month, the church invites jazz fans to participate in its “Love Supreme Meditation.” The lights are dimmed, and the congregation hears Coltrane’s spoken-word poetry from the album: “I will do all I can to be worthy of thee, O Lord....There is none other. God is. It is so beautiful.”

The church has faced spiritual and logistical challenges over the past five decades. In 1981, for instance, the Kings battled a lawsuit from the musician’s widow, Alice Coltrane, after what the Kings say was a theological falling out. (Among other things, Alice wanted a more staid approach: fewer saxophones, more meditation.) The congregation has moved often amid San Francisco’s cycles of gentrification, enjoying seven addresses since 1969. In 2022, the church moved to its current home at 2 Marina Boulevard. The African Orthodox Church granted sainthood to Coltrane in 1982.

Services at Saint John’s are held each Sunday at 11 a.m., with a combination of Coltrane’s spoken-word recordings and traditional Scripture. The Kings’ ecstatic experience of discovering Coltrane is reflected in the church’s Byzantine-style paintings (above) that depict Coltrane in a white robe, flames flaring from his saxophone.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4f/df/4fdf6eb6-84ac-417d-b362-acd854814dbc/microsoftteams-image_2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)