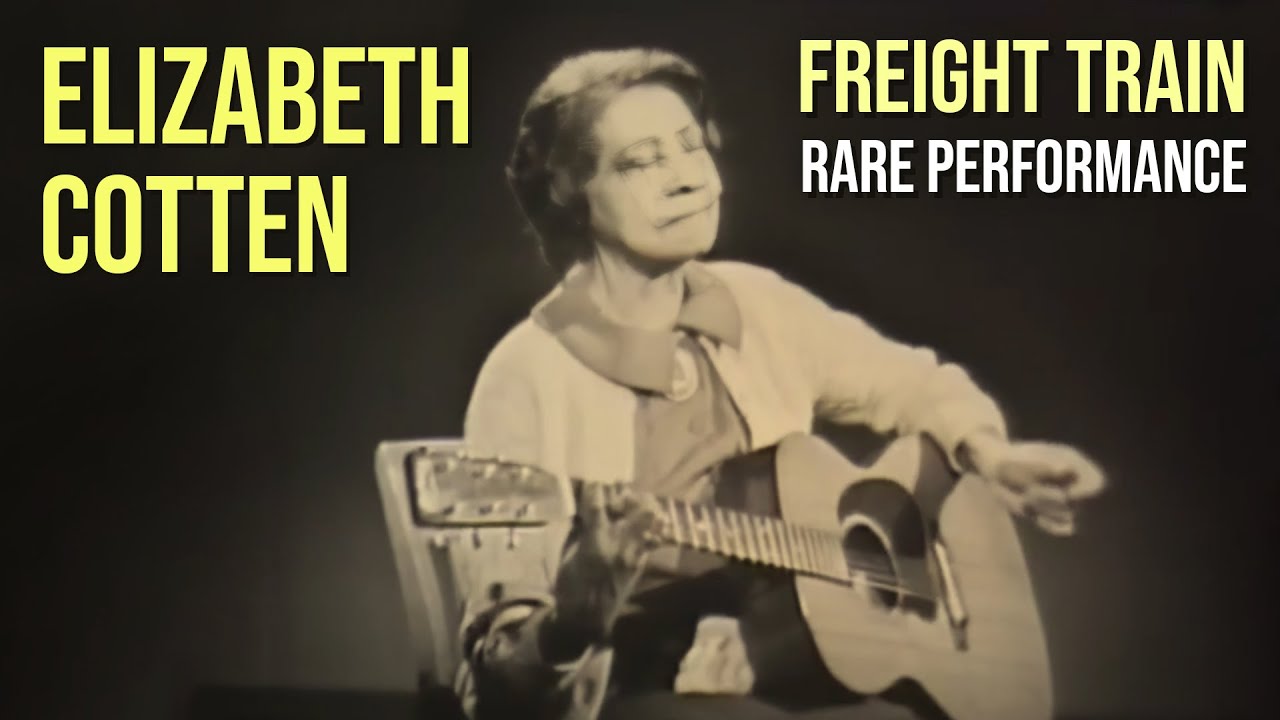

How This Self-Taught Guitarist Became a Music Legend

For decades, Libba Cotten was one of the most distinctive folk musicians in America

:focal(1800x1354:1801x1355)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9a/52/9a52a82b-f2a7-4e58-a3d4-3b9f2f4ef7f5/libba.jpg)

When Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten was around 8 years old, she would slip into her older brother’s room when he was at work, take his banjo off the wall and toy around with it. Immediately, though, little Libba ran into a problem: She was left-handed, while the instrument was right-handed. No matter. The determined young girl simply turned the banjo upside down and taught herself to play that way. For the treble, or higher notes, she used her thumb; for the bass, her fingers. In time, this distinct finger-plucking approach—characterized by its rhythmic, percolating sound and its lively, emotive melodies—would become known as “Cotten Style,” and these early years of musical exploration served as a prelude to a life and career in which Cotten did everything on her own, wholly original terms.

Born Elizabeth Nevills in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, around 1893, Cotten saved money from her jobs as a babysitter and domestic worker and bought her first guitar for $3.75 (around $130 today) when she was around 11 years old; she named the instrument Stella. By 12, she had written “Freight Train,” a lilting song that movingly captures the sense of liberation that trains symbolized for Black Americans in the South. “Freight train, freight train, run so fast,” Cotten sings on the chorus. “Please don’t tell what train I’m on / And they won’t know what route I’m going.”

Though Cotten is now something of a legend among folk-music enthusiasts, she didn’t achieve commercial success until quite late in life. Intensely religious, she gave up playing the “worldly” music of folk and blues when she was 15, choosing to marry a man named Frank Cotten and to devote herself to family and God. She and Frank had a daughter, Lillie, when she was 16, after which the family moved to New York City, where Cotten remained until divorcing Frank in the mid-1940s.

Relocating to Washington, D.C., where she helped Lillie, by then in her 30s, raise her new baby, Cotten found work cooking and cleaning at the home of the Seegers, a musical family that included singer Pete; his musician half-brother, Mike; their ethnomusicologist father, Charles; and Charles’ composer wife, Ruth. One day, Cotten picked up one of the Seegers’ guitars and started plucking—and her employers were floored. Realizing her immense talents, the family encouraged her to pursue a career as a musician.

Mike Seeger produced Cotten’s debut album, Folk Songs and Instrumentals With Guitar, in 1958. Two years later, she held her first public performance, alongside Mike Seeger at Swarthmore College. In the ensuing decades, Cotten became a highlight on the folk music circuit, playing at the Newport Folk Festival and many others. Soon, she was a breakout star, finding fans nationwide, as well as advocates among music icons including Joni Mitchell, who struggled to imitate Cotten’s style in her own playing. At the age of 85, Cotten finally performed at Carnegie Hall in 1978.

Her lively stage presence is in joyful evidence on her fourth release, Elizabeth Cotten Live!, which won a Grammy Award in 1985 for Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording. She died two years later, at 94, leaving behind a legacy that influenced players from Jerry Garcia to Rhiannon Giddens.

Cotten never shied away from talking about the steep challenges she was forced to confront while learning to play the guitar. “No one helped me. Everything I play for y’all tonight, I give myself credit, ’cause nobody helped me,” she half-jokingly told an enthusiastic crowd in 1983.

One of the most striking artifacts from Cotten’s life is her 1950 Martin guitar, which curators at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History believe she played for many years—possibly including at that Carnegie Hall show. The instrument has a mahogany body and neck and a rosewood fingerboard and bridge, and it sits on display at the museum’s “Sounding American Music” exhibition. What’s especially remarkable about the guitar, says John Troutman, a curator at the museum, is how it reveals, through its wear, the upside-down style of playing that made Cotten unique: “You can see the grooves worn from her index finger where she was plucking the bass notes.”

In this way, Cotten’s instrument exemplifies, in powerful fashion, the ways in which she made the instrument adapt to her, and to the notes that she heard in her head, transmuted through her unique picking into something immortal.