Janice Arnold leads the nomadic life of the 21st-century artist, moving around the country and the globe, from museum exhibition to master class, from corporate installation to community event. Since she made her first felt, in 1999, she has been devoted to the study of wool fiber and the felting process. In travels through Mongolia, Nepal, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Turkey, among other places, she has studied or taught—learning about the historic, cultural and spiritual significance of the material in those countries, or sharing new felting techniques developed in her studio and lab, housed in a former schoolhouse near Centralia, Washington.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cb/4a/cb4ab7aa-a3b3-4406-9eff-b30fcb4dddc0/julaug2023_m15_textileartists.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/eb/03/eb03614c-b440-4305-8a73-129a8822418b/julaug2023_m26_textileartists.jpg)

The material most often used in the process of felting is wool. The scaly outer surface of the fiber causes it to shrink and become permanently entangled when it is wetted and agitated (like a wool sweater that accidentally ends up in the washing machine). The more it is rolled, rubbed and beaten, the denser and stronger the resulting fabric becomes.

Arnold explores the extremes of what is possible with the material, whether making stone-like slabs of solid wool or delicate, translucent webs using mere wisps of fiber. Other materials can be ensnared by wool fibers, buckling and rippling as the wool shrinks. Arnold exploits these traits to create a palette of textures resembling everything from elephant skin to tree bark to molten lava.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/66/ea660116-9aa5-4fd5-99e6-2f12b3469383/julaug2023_m14_textileartists.jpg)

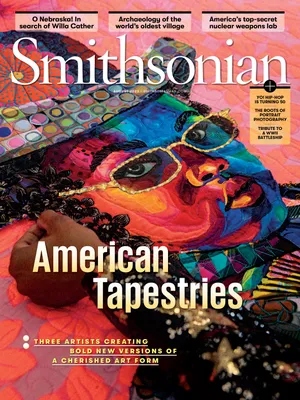

The artist prefers working on an ambitious scale; I first met Arnold when she created Palace Yurt in the conservatory of the historic Andrew Carnegie mansion that houses the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in 2009. This past April when I met with her, she was installing a large-scale work she has titled Homage to Water inside the headquarters of the Washington State Department of Ecology, in Lacey, Washington. The central feature of the 1993 building’s atrium is a long, rectangular rock garden, which reminded Arnold of a dried-up stream. She has long yearned to reactivate the space, bringing the color, flow and sparkle of water to the rocky beds.

The installation was being phased over several weeks, engaging the interest of the staff returning to post-pandemic, in-person work. First, a “spring” in the form of unworked wool fiber bubbled up in the lobby. Soon “water” began flowing in the form of felted panels that transition gradually along their length through a half-dozen shades of blue. Eventually, 438 feet of handmade wool felt will meander through and among the rocks, evoking deep-blue pools, quicksilver channels and turbulent whitewater. The rocks are dotted with tufts of green moss, also fabricated by Arnold in a unique felting process that pairs velvet with wool fiber.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/84/89/84894f1a-ef03-45c4-b833-ed42328302cf/julaug2023_m11_textileartists.jpg)

The building’s occupants have responded warmly to the installation, and to watching the artist at work. Stacey Waterman-Hoey, an analyst at the Department of Ecology, said “the ‘wool river’ adds a bright liveliness and sense of wonder to a space that is devoid of the core feature it hints at: water. Water symbolizes renewal and is both energetic and soothing. Wool remarkably mimics this effect.” The installation was scheduled to open to the public on June 27.

About half of the panels are repurposed from an installation originally created for the Grand Rapids Art Museum in Michigan, where they soared vertically at the entrance to Chroma Passage, which transformed a glass-lined hallway into a cathedral-like gallery in which a lacy canopy transitioned through the color spectrum. The blue panels from that installation have come down to earth and are now winding their way across the riverbed, where they will be joined by newly made panels.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/d6/42d6879b-e63b-41b2-8861-e53aea59414a/julaug2023_m16_textileartists.jpg)

Each of the new panels is composed on a long lay-up table in Arnold’s studio and begins as a collage of loose wool fiber, gradually transitioning from white to deep blue. In addition to regionally sourced wool, the composition includes scraps of metallic organza, recycled burlap sourced from nearby coffee roasters, curls of locally raised mohair and—to create the effect of sunlight sparkling on the surface of water—hand-dyed indigo lyocell. The lofty mat, some four inches thick, is transported to an outdoor table where it can be thoroughly wetted before being rolled and placed on the felting machine, which is custom designed to apply both pressure and friction. To ensure balanced firmness across its length, the piece is unrolled and rerolled from the opposite end between each session on the machine—typically 15 to 18 times, but occasionally as many as 30.

Water is an integral part of making felt, and gallons of it are used to saturate the wool at every stage, requiring that Arnold work outdoors all year round. Spring weather certainly makes the heavy, wet work more pleasant. Among traditional pastoralists, felt-making is seasonal: Sheep are generally shorn in spring, and felts are made to prepare for the winter ahead.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/b6/03b6b3b1-3527-4641-89fe-72e02a409dcc/julaug2023_m10_textileartists.jpg)

Another major installation by Arnold is Cave of Memories. The large, remarkably delicate panels were first shown in 2017 at an exhibition titled “FELT DeCoded | Wool: Nature’s Technology,” which Arnold conceived of and curated for San Francisco’s Museum of Craft and Design. Suspended from the ceiling, the panels formed a high-peaked canopy inspired by the goat hair tents used by Bedouins. The airy, lace-like panels feature a spiral pattern, a universal symbol of eternity and continuity, and showcase the lightness and transparency that are possible with this typically sturdy material. The immersive installation, created shortly after she spent three years as primary caregiver to her aging parents, was a meditation on strength and fragility, and a tribute to the energy and intention of providing care.

Last year, Arnold carried several of those panels in her suitcase to Almaty, Kazakhstan. Hung in simple tent-like fashion and weighted down with stones selected from a local mountain stream, they were used as projection screens for a series of videos of the natural environment surrounding her home and studio. “I refer to these pieces as ‘nomadic,’” Arnold has said. “In keeping with tradition, these pieces are designed to be portable and easily hung to harmonize with each unique place and space.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/78/aa/78aa339a-7ab1-4aa8-a455-6f11c75d28ba/julaug2023_m12_textileartists.jpg)

This summer, at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall, Arnold will collaborate with the Union of Artisans of Kazakhstan in a program titled “Soul of Tengri: Kazakh Traditions and Rituals.” The group is developing a demonstration that will incorporate some of the individual Cave of Memories panels. The programming will honor the nomadic philosophy of ecological balance, sustainability and the sacred nature of felt, which is integral to Kazakh life from birth to death.

Arnold increasingly collaborates with others, gathering diverse groups to work together to create large-scale felts. In Tieton, Washington, for example, community members cooperated to create Mighty Tieton Monster Felt, a project developed with Mighty Tieton, an incubator for artisan businesses. The 32-by-15-foot piece of felt began as 65 pounds of donated wool and alpaca fibers, carefully laid out by volunteers on the floor of a former apple warehouse. The wool was covered with a net for protection, then saturated with warm water. People gently walked barefoot across the wet wool to begin the felting process, then staged a four-hour dance party, jumping around on the wet wool to effect the initial transformation from fiber to felt.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/94/6b9443fd-8fe5-40b5-8372-c1940f18c4bb/julaug2023_m29_textileartists.jpg)

Over subsequent years, the community has continued to gather to work on Monster Felt. Following Central Asian felt-making customs, the enormous felt roll has been kicked down the road by teenagers linked arm in arm and pushing with their feet. It has been dragged around a field behind a horse and has been rolled on the forearms of volunteers working together on their knees, bonding fibers together through collective effort. In between, it has been part of exhibitions, performances and celebrations. Today, participants work together quilting-bee-style to stitch maps of their local communities into the Monster Felt’s border, based on hand-drawn maps made by Arnold’s father, a cartographer.

“Making things together creates a social relationship that is primal and very human,” she said. “Sharing physical work together to make something larger than one can make alone creates a strong social fabric.”

:focal(1445x1087:1446x1088)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/69/5d/695d9d00-98c9-437d-a914-36f02852db9d/julaug2023_m13_textileartists.jpg)