Before He Wrote a Thesaurus, Roget Had to Escape Napoleon’s Dragnet

At the dawn of the 19th century, the young Brit got caught in an international crisis while touring Europe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/7f/ff7fa883-1977-4aff-9a12-ca4a0c683f96/roget.jpg)

In January 1802, Peter Mark Roget was an ambivalent young medical school graduate with no clear path. He lacked the professional connections that were crucial to a fledgling English physician and was eager for a reprieve from a life largely orchestrated by his widowed mother, Catherine, and his uncle and surrogate father, Samuel Romilly, who together had steered him to study medicine.

Roget had spent the previous four years since his graduation taking additional courses and working odd jobs, even volunteering in the spring of 1799 as a test subject at the Pneumatic Institution in Clifton, England, for a trial of the sedative nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas. With no immediate professional path, he felt unsettled and despondent. Romilly suggested a change of scenery. Accordingly, he introduced his nephew to John Philips, a wealthy cotton mill owner in Manchester, with the plan that Roget would chaperone Philips’ teenage sons, Burton and Nathaniel, who were about to embark on a year-long trip to the continent to study French and prepare for a career in business. Roget had caught a big break—or so he thought. The timing, it turns out, could not have been worse, and so began a telling adventure in the early life of a man now known worldwide for his lexicography in his Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases, one of the most influential reference books in the English language.

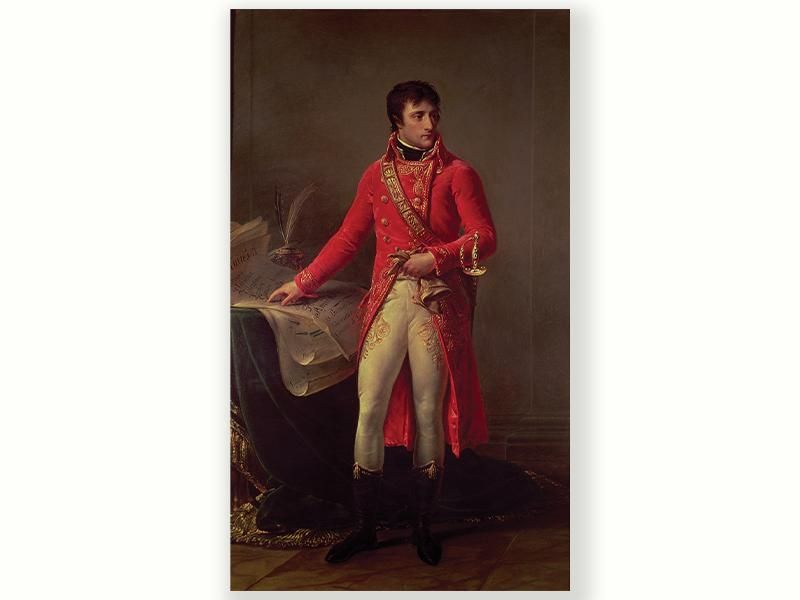

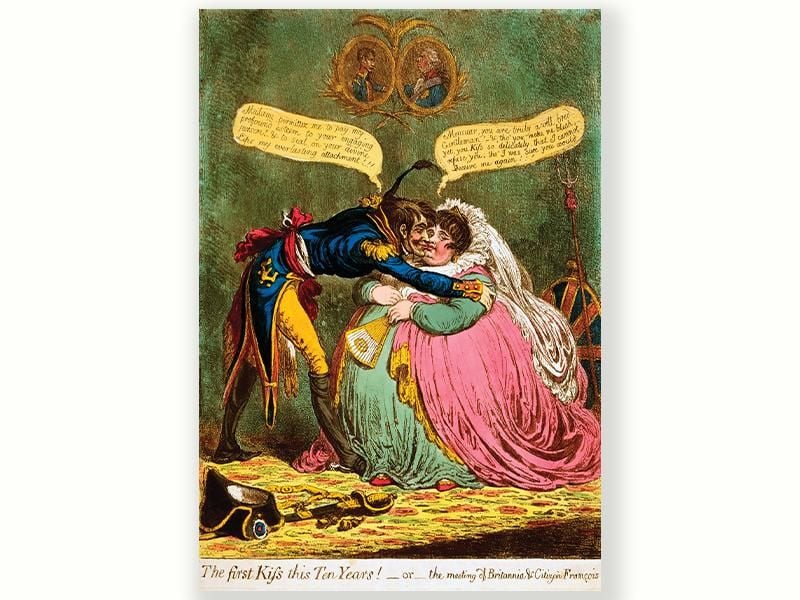

The French Revolutionary Wars, during which France declared war on Great Britain in 1793, had been halted by an armistice in the fall of 1801, under the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. With a peace treaty set to be ratified in the northern French town of Amiens the following March, British travelers were jamming the boats that plied the English Channel, eager to set foot in Paris for the first time in almost a decade.

Roget and his two charges left London in February 1802, a few weeks after Roget’s 23rd birthday. Their journey followed many aspects of the traditional Grand Tour, a rite of passage for young British aristocrats. Armed with letters of introduction, along with a salary of £400 for Roget, plus money for expenses, the travelers boarded a packet boat—a midsized vessel carrying mail, freight and passengers—and crossed from Dover to Calais. There, Roget hired a three-horse carriage, which transported them through the northern French countryside to Paris.

The trio’s first three months in Paris were relatively uneventful. Roget enlisted a French tutor for the boys and took them on daily outings to the Museum of Natural History to study science. They visited the Louvre and Notre-Dame Cathedral, enjoyed afternoon strolls along the Bois de Boulogne and attended the theater regularly. The actors, Nathaniel noted, were “superior to any we have in London.”

Not all their verdicts were positive. “I begin to like the cooking better; yet I shall never take to the ‘Fricandeau,’ which is a terrible dish—composed of beef, spinach oil and bacon,” Nathaniel wrote to his parents. Roget, for his part, bemoaned the country’s apparent lack of hygiene. The pavement stones were “greasy and slippery,” he wrote, and the “men in general wear cocked hats, and are very dirty in their persons; they wear large ear-rings, and often allow the beard to descend from the ears under the chin.”

For centuries, travel to France had provided wealthy Brits with the chance to pronounce judgments on their geopolitical rivals, escape from the damp fog of England and revel in the magnetic charms of Paris. France in 1802 offered something new—the prospect of seeing Napoleon, of whom “everybody wanted to catch a glimpse,” notes Jeremy Popkin, a historian at the University of Kentucky.

Just weeks into their stay, Roget and the boys had their first chance to see the great man, at the Tuileries Palace in early March. “He is thin and of low stature; his countenance, though meager and sallow, is extremely animated, his eyes black and piercing, his hair black and cropped, his dress remarkably plain,” Burton wrote. They saw him again on Easter Sunday, in a regal procession celebrating his resuscitation of the Catholic Church, which had been a target of antireligious policies during the Revolution. “Bonaparte bowed in response to the applause of the populace. His carriage was drawn by eight superbly decorated horses,” Nathaniel reported in April. “The great bell of Notre-Dame, which had been silent 10 years, was rung,” along with a 60-gun salute.

The toll of the Revolution became most evident when the trio departed Paris for Geneva in May. En route, they surveyed the dilapidated 12th-century Palace of Fontainebleau. “It might formerly have been well worth seeing, but it has suffered greatly from the fury of the mob; and now, stripped of its ancient honours, it stands a monument of the devastation wrought by the revolutionary storms,” Roget wrote.

Geneva, by contrast, greeted Roget and the boys with glorious vistas of the Alps and their first taste of frog pâté. But here, almost a year into their blissful tour, they found themselves trapped, amid a flare-up of hostilities between Britain and France. An increasingly imperious Bonaparte expanded his territorial reach into northern Italy, northwest Germany, Holland and Switzerland, thereby impinging on Britain’s foreign trade. King George III lamented the French ruler’s “restless disposition,” and on May 18—a little more than one year after the armistice—Britain declared war on France.

In retribution, Bonaparte issued a decree that all British citizens in French territory over the age of 18 be held as prisoners of war—including those living in Geneva, an independent city-state that Napoleon had annexed. Roget was stunned. “The measure was so unprecedented and so atrocious as to appear destitute of all foundation,” he wrote. But Geneva’s commandant, a man named Dupuch, made it clear that English adults were under strict orders to surrender and be transported to Verdun, a small city in northeast France, where they would be required to find lodgings of their own, or else be put up in barracks. Although British captives were not in literal prisons—they even attended the theater and horse races—they were denied many basic freedoms.

The Philips boys were too young to be subject to Napoleon’s edict, but Roget was leery of sending them off alone. His first instinct was for the three of them to flee. But after taking a carriage to the outskirts of the city, they discovered that gendarmes had been placed at every exit route to stop escapees. Retreating to their lodgings, Roget petitioned officials in Paris for exemptions as a medical doctor and a tutor of two teenage boys. These entreaties failed. Now deeply panicked about the safety of his charges, Roget sent the boys over the border to the Swiss Confederacy—first to one of John Philips’ business associates in Lausanne, and then farther north to Neuchâtel—to await his arrival.

In mid-July, Roget resorted to a final, desperate course of action: changing his citizenship. His father, Jean, was a Genevese citizen who had grown up in the city before moving to London as a young adult, and had died of tuberculosis in 1783. On July 21, Dupuch, the commandant, growing impatient with Roget’s efforts to elude captivity, demanded that Roget present Genevese papers by 7 a.m. the next day; otherwise, Roget would join his fellow countrymen who were being readied for Verdun. Somehow, Roget managed to track down Jean Roget’s baptismal certificate as well as a regional official who could authenticate the father-son relationship. The official was playing boules at a club when Roget found him and did not want to be disturbed, but a financial incentive changed his mind. “At length, by tickling the palm of his hand, he promised to be ready for me by 6 the next morning,” Roget wrote.

On the 26th of July, with Genevese citizenship documents in hand, Roget hastened to Neuchâtel and reunited with the boys. But their ordeal was hardly over. The passport Roget had obtained in Geneva was invalid for further travel, and he needed new paperwork to journey north. Unable to obtain this paperwork quickly, he and the boys simply made a run for it. Dressed in shabby clothing, so as not to look like the tourists they were, they traveled through obscure villages, avoided speaking English and, after bribing a French guard in the border town of Brugg with a bottle of wine, crossed the Rhine River by ferry to unoccupied German soil. “It is impossible to describe the rapture we felt in treading on friendly ground,” Roget wrote. “It was like awaking from a horrid dream, or recovering from a nightmare.”

Back in England, Roget launched his career as a physician and inventor in 1804 at the age of 25, going on to lecture and publish extensively. In 1814, the year Bonaparte abdicated as emperor, Roget published a paper about a logarithmic slide rule he had invented, earning him election as a fellow to the Royal Society of London at the age of 36. His most momentous work was an exhaustive surveillance of physiology in the vegetable and animal kingdoms, which composed one of the celebrated eight Bridgewater Treatises, a series of books published in the 1830s that considered science in the context of theology.

In 1849, after retiring from medicine and science, the 70-year-old turned to words, a passion that harked back to his childhood, when he had filled a notebook with English translations of Latin vocabulary and then classified them into subject areas. Roget’s early passion never dissipated: In his mid-20s, during off hours, the young doctor compiled a list of some 15,000 words—a “little collection,” he later called it, that, although “scanty and imperfect,” had helped him in his writing over the years.

Now a man of leisure, Roget unearthed his earlier compilation. One of Roget’s greatest gifts, his biographer D.L. Emblen writes, was a determination “to bring about order in that which lacked it.” Over the next three years in his Bloomsbury home, just steps from leafy Russell Square, Roget assembled his words into six overarching categories, including “matter,” “intellect” and “volition.” Roget’s work echoed the organizational principles of Carl Linnaeus, the pioneering 18th-century taxonomist. Neither a dictionary nor simply a collection of similar words, Roget had sorted and classified “all human knowledge,” Emblen notes emphatically.

Although prior books of synonyms existed, none offered the depth or scope of the thesaurus that Roget published in 1853, and for which he would become a household word—a synonym for the source of all synonyms. Over the next 16 years, Roget oversaw more than two dozen additional editions and printings—so many that the stereotype plates created for the third volume in 1855 eventually wore out.

Genius is rooted in an incessant quest for knowledge and an imagination that transcends boundaries. Roget’s early travels exposed him to foreign cultures and new terrain; science gave him structure. After his death on September 12, 1869, at the age of 90, Roget’s son John took up editorship of the thesaurus. In an introduction to the 1879 edition, John reported that his father had been working on an expanded edition in the last years of his life, scribbling words and phrases in the margins of an earlier version. His mind never stopped.

There's a Word for That

Lexicographers compiled practical—and whimsical—guides to synonyms centuries before Roget

By Teddy Brokaw

Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae, sive Origines, c. 600-625

Synonymy—the concept of distinct words signifying the same thing—was understood as far back as Ancient Greece, but the Archbishop of Seville authored the earliest work modern readers might recognize as a thesaurus. Writing in Latin, Isidore sought to help readers distinguish between easily confused words: “Drinking is nature, boozing is luxury.”

John of Garland, Synonyma, c. 1225-1250

This English grammarian’s work was one of the first attempts to teach budding orators to punch up their speech by using different words to express the same idea. Organized alphabetically, like a modern thesaurus, it was written entirely in Latin verse and meant to be committed to memory. Garland encouraged orators to be attentive to context: A barking canis might be man’s best friend, but a swimming canis would be a “sea-dog”—a shark.

Erasmus, Copia, 1512

The Dutch humanist’s book of Latin rhetoric went through nearly 100 print runs. It would influence many future writers, including Shakespeare. Erasmus delighted in showing how a sentence could be rephrased almost limitlessly. He demonstrated 150 ways to express “Your letter pleased me mightily,” for example: “Your epistle afforded me no small joy.”

Gabriel Girard, La Justesse de la langue françoise, ou les différentes significations des mots qui passent pour synonymes, 1718

The French abbot emphasized the distinctions between similar words in his synonymary: A man is “stupid” because he cannot learn, but “ignorant” because he does not learn. His book was a runaway success, inspired a wave of imitators and influenced Voltaire and Diderot.

Hester Piozzi, British Synonymy, 1794

The English writer produced the first original English work of synonymy after seeing her Italian husband struggle with conversational English. Despite her lexicographical prowess, Piozzi limited her book to the realm of “familiar talk.” Her Synonymy was reprinted several times, including a heavily censored French edition published as Napoleon came to power—and which was conspicuously missing its entry for “tyranny.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Claudia_Kalb_Author_Photo_1.jpg)