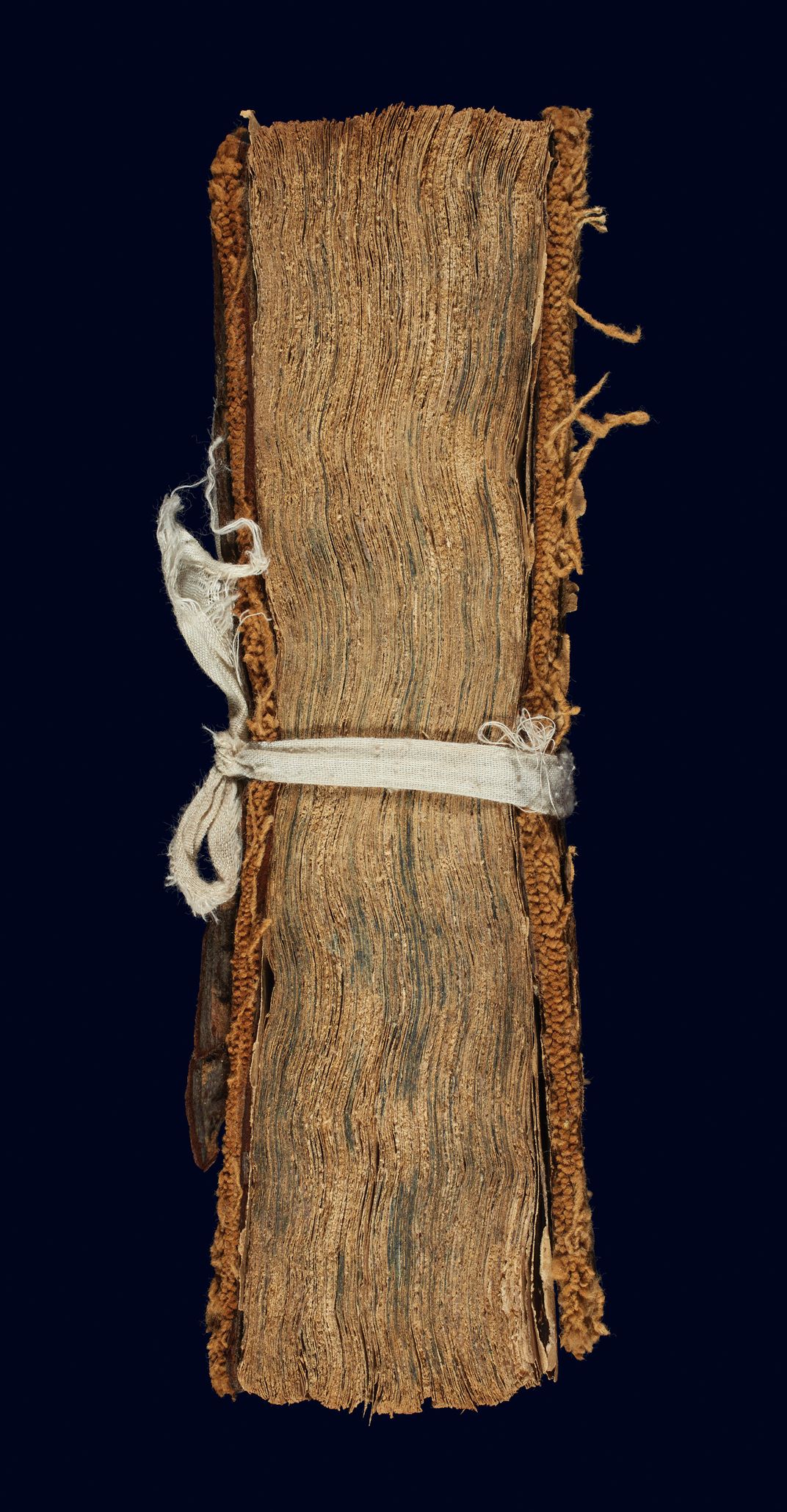

When Columba Stewart, a 63-year-old Benedictine monk based in Minnesota, arrived at the Kaiser Library, a government-affiliated archive in Kathmandu, Nepal, he stared up at the three-story building—wobbly, riven by cracks, too unsafe to use. It was three years after the massive Nepalese earthquake of 2015 that had killed 9,000 and laid flat much of the Kathmandu Valley. Rain leaked through holes in the roof, inundating broken masonry and congealing into gray mud on the floor. Many of the library’s manuscripts, some dating to the ninth century and written in Devanagari script (an ancient orthography system still used across the Indian subcontinent) on birch bark and palm leaves rolled up and held by clay seals, had been moved downstairs. The scrolls were stacked in bags and shoved into old glass cabinets on the ground floor. Exposed to the dust of an ongoing construction project to shore up the building’s weakened structure, as well as occasional seismic vibrations, the works were at risk of rapid disintegration.

Stewart had flown to the Himalayas at the behest of Bidur Bhattarai, a Nepalese scholar at the Centre for the Studies of Manuscript Cultures at the University of Hamburg, who had traveled to his homeland after the quake to assess the damage. Library employees recounted their panic as books crashed to the floor and chunks of bricks and rocks came hurtling down: For months they had been forced to work outside under a tarp. “I saw things fallen down, and the dust covering everything, and I realized that if it happens again, we will lose these precious things,” Bhattarai recalled to me.

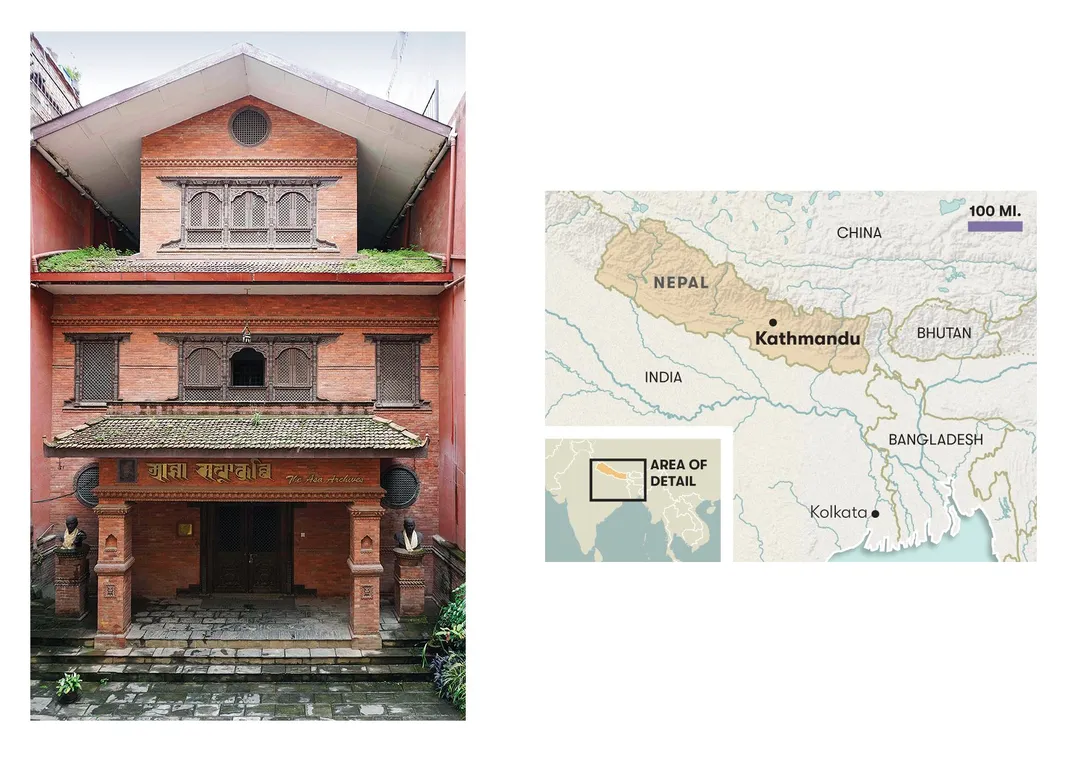

Stewart made three trips to Nepal in 2018 and 2019 (a spring 2020 visit was called off at the start of the Covid-19 worldwide lockdown), continuing discussions to begin digitizing the Kaiser Library’s collection, while initiating a pilot project at a nearby private institution: the Asha Archives. Its collection of 7,000 richly ornamented manuscripts on bound paper and rolled palm leaves was built up by Prem Bahadur Kansakar, and named after his father, Asha Man Singh Kansakar, a prominent early 20th-century social activist and writer from the Newari ethnic group—the historical inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley and the dominating force in Nepali politics and culture—and donated to the public in 1987. The works are housed in a centuries-old building that typifies Newari-style architecture, noted for its brickwork and elaborate carved wooden facades. Miraculously, the structure had survived the earthquake intact.

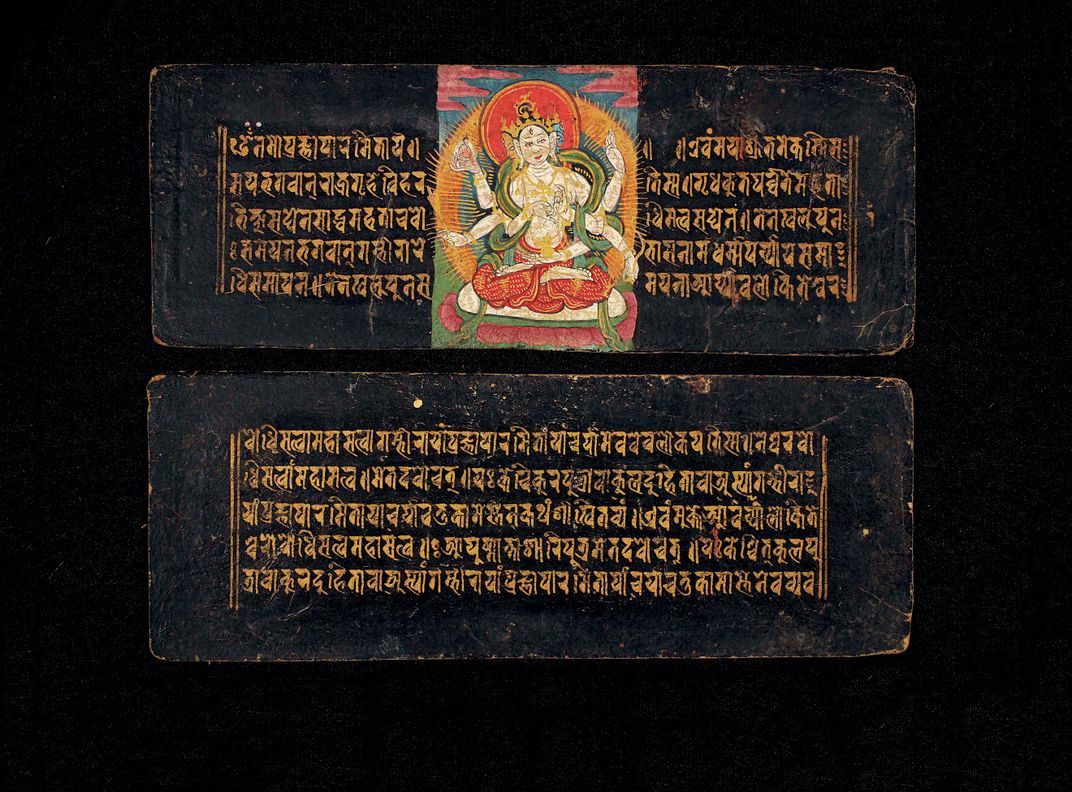

Working remotely from his stateside base, Stewart supported Bhattarai in training a team of four Nepalese staffers to begin digitizing 1,000 manuscripts newly donated to the archives. Almost all were written on traditional Nepalese paper by Newari scribes. The works treat subjects including Buddhist and Hindu philosophy, religious rituals, Ayurvedic medicine (a holistic approach based on ancient Hindu writings) and grammar, along with poetry, written in Sanskrit, Newari and Nepali and dating to the 15th through early 20th centuries. Most had been wrapped in red- or yellow-dyed cotton for centuries, and recently have been rewrapped in undyed muslin or locally produced paper for conservation purposes. The religious works show a uniquely syncretic approach, typifying Nepal’s position at the crossroads between India and Tibet. “Everybody knows Nepal because of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries,” Stewart says, “but there’s also strong Hindu presence. The manuscript tradition witnesses that mix, in a variety of languages. Nepal is a meeting place; that’s what makes it so interesting.”

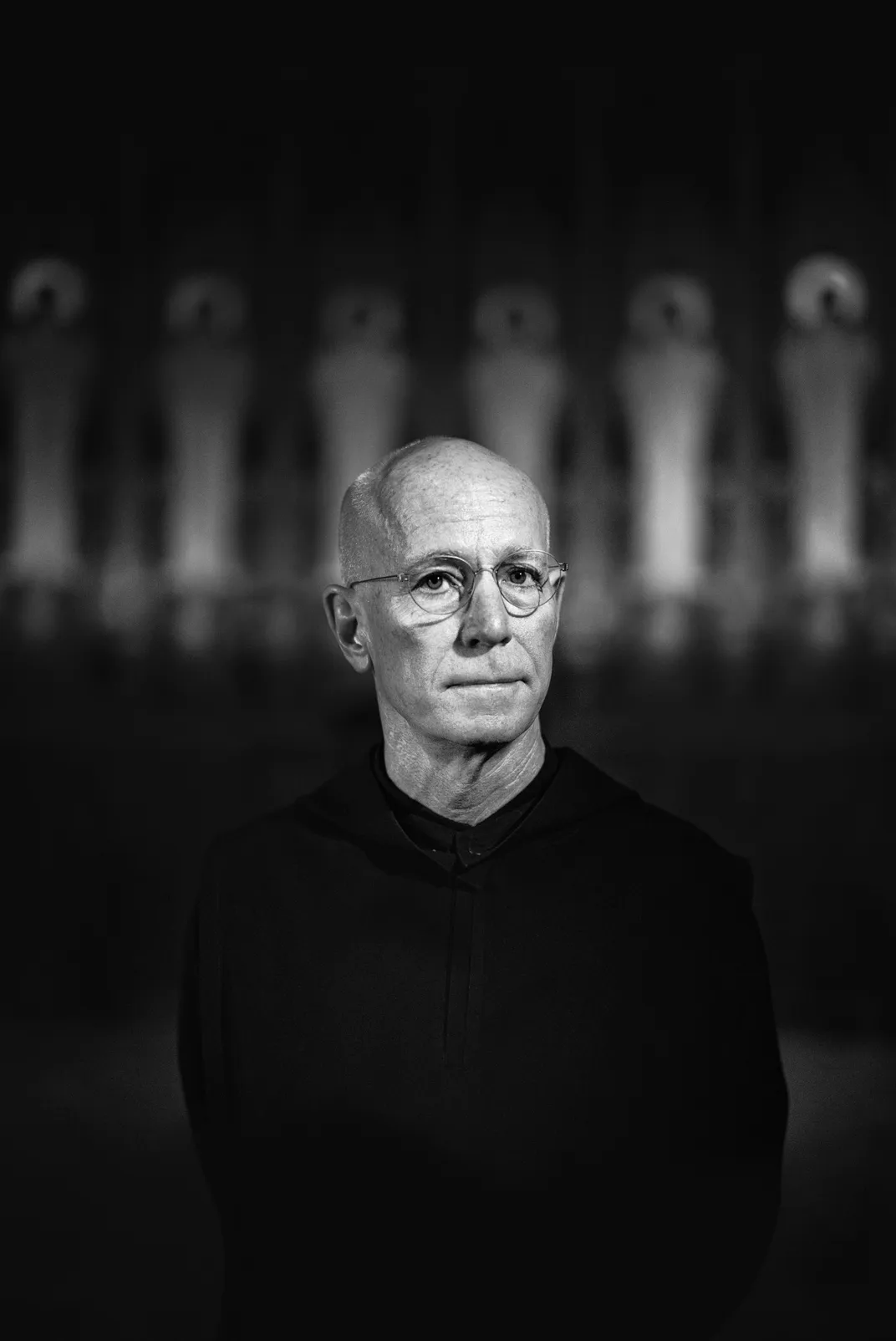

Stewart lives and works at St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota, where he is a professor of theology at the affiliated St. John’s University and the executive director of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML), the world’s largest online repository of ancient Christian and Islamic texts. His effort in Nepal is just the latest literary rescue mission for the world’s most renowned, prolific and peripatetic manuscript conservationist. Over the past 20 years his work has taken him from the Balkans to the Himalayas, from the Sahel region of Africa to the Middle East, injecting him into the heart of conflict zones and resulting in several narrow escapes from rebel movements and religious extremists.

His adventures certainly defy the conventional notion of monastic life as sedentary and quiet. “It’s a weird situation,” Stewart acknowledges in a Zoom call as he sits at his desk in the library in Minnesota during an enforced break from travel during the pandemic. “Sometimes I feel like a war correspondent. Other times I’m cast in a religious role. In northern Iraq, I’ll be in my habit at Mass with 1,500 worshipers chanting in Aramaic. Then I’ll be going around in a tank.” Mementos on his shelves provide glimpses of his globe-trotting life: a United Nations pass from Timbuktu, photos of Stewart with Pope Francis, a Hezbollah charm bracelet.

Courtly and trim, he is wearing a black mock turtleneck, which he alternates with his black monastic habit. Stewart lives austerely in the abbey and participates in five daily prayers with his fellow monks, beginning at dawn, ending at 5 p.m. In between the religious rituals, he immerses himself in his other passion: literature.

Stewart has built up an extensive rare-book collection for the library. On a virtual tour using his iPad, he takes me down to the basement, and removes from a shelf one of his favorite recent additions: a four-volume Old and New Testament, bound in oak, and printed in Nuremberg in 1480, twenty-five years after the Gutenberg Bible rolled off the printing press. The fine workmanship of this early holy book appeals to Stewart, whose father, an engineer, used to take him on weekend tours of construction sites around Houston, where the family lived. “The paper looks like it was made yesterday,” he tells me. “The ink is black as can be, mixed with linseed oil to take the bite out of the type,” he says. “Every piece of type was set by hand, backwards. They had to do that for every single page. That’s an extraordinary achievement in the service of knowledge.”

Founded by St. Benedict of Nursia, a sixth-century hermit-turned-evangelist in southern Italy, the Benedictine order has a long history of disseminating and preserving the written word. In the Middle Ages, monks wrote and copied Bibles, liturgical works and secular texts, and later produced such works on printing presses. But over the past century, global conflict and sectarian strife have cast the order into a new role as literary conservationists. In 1965, two decades after the devastation of World War II—including the 1944 razing of the Monte Cassino abbey in Italy—and with the specter looming of a nuclear showdown, Benedictine monks from St. John’s Abbey and University in Minnesota undertook to preserve on microfilm Latin manuscripts in Benedictine libraries across Europe.

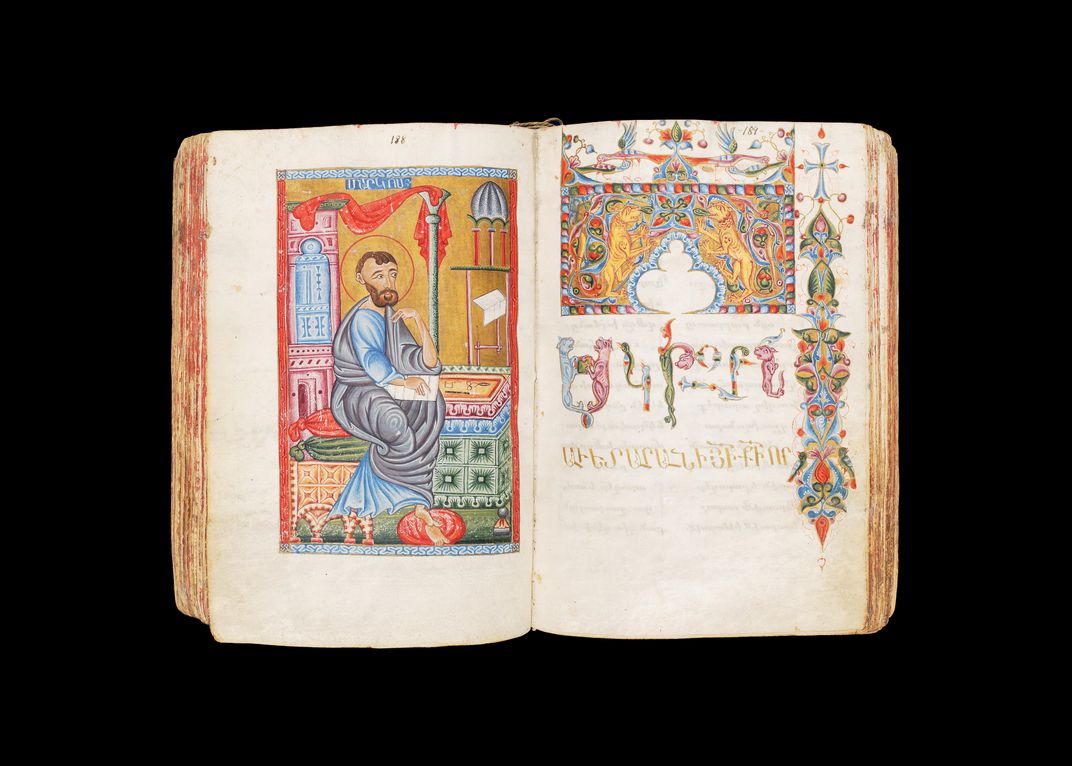

Stewart’s work represents a high-tech evolution of the Benedictine mission. He conducted his first digitization project in 2003, in Lebanon, and went on to the rest of the Middle East and the Balkans, where Christian minorities have grown increasingly vulnerable, their cultural patrimony put at risk. Word of his deeds spread. Malian librarians who had rescued 250,000 Islamic and secular manuscripts from Al Qaeda in Timbuktu by smuggling them to Bamako enlisted his aid. Muslim communities in India, threatened by the Hindu extremist rhetoric of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, have turned to him for help digitizing their archives. “Much of what we do is networking and serendipity,” Stewart says.

Stewart grew up in a practicing Catholic household in the 1960s, his parents a teacher and civil engineer. At Harvard, he studied literature and history. He also attended Mass on a regular basis. Stewart briefly considered the priesthood, but found the prospect of living on his own in a rectory unappealing.

Then, while preparing to write a dissertation at Yale on early Christian liturgy, he befriended two monks on a study leave from St. John’s Abbey, founded in the 1850s by German Benedictines to provide pastoral care, education and medical treatment to German-speaking immigrants in Minnesota. Invited to visit the abbey and adjoining liberal arts college, Stewart found the 2,700-acre campus intoxicating. He was equally attracted to the 1,500-year tradition of monasticism, with its life of self-discipline, prayer and collegiality. “It’s like joining the military—the esprit de corps, the uniform, the sense that you’re a part of something bigger than yourself,” he says. He left Yale, spent a year in the novitiate, then three years under temporary vows. After four years, he says, “I was all in.” Later, at Oxford, he completed his dissertation, focused on premonastic currents in early Christianity, and joined the St. John’s faculty. He was prepared, he said, for a life of teaching and religious devotion.

That bucolic vision was disrupted when the university president, aware of Stewart’s knowledge of early Christian sites in the Middle East, asked him to take on a manuscript preservation project for the Orthodox Christian church in northern Lebanon. That segued into forays across the Bekaa Valley to Aleppo, Syria, one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, to photograph ancient manuscript collections of the Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Catholic churches, written in Aramaic, the lingua franca of the ancient Near East. The project ended abruptly in the Arab Spring of 2011, when anti-Assad protests escalated into a civil war in which more than half a million people have died. Among the casualties was one of his scholarly collaborators, the Syriac Orthodox archbishop of Aleppo, Gregorios Yuhanna Ibrahim, who was seized by gunmen along with Greek Archbishop Boulus Yazigi, on April 22, 2013. Neither was seen again. They were presumably murdered in what Stewart believes was a “kidnapping for ransom gone wrong.”

Stewart has had a few close calls himself. In 2007 he began working in northern Iraq alongside Najeeb Michaeel, a Dominican friar from Mosul, who had gathered thousands of precious Christian manuscripts for safekeeping in a Christian village called Qaraqosh. Because Americans remained a target after the 2003 U.S. invasion and the rise of Islamist radicalism, Michaeel introduced the French-speaking Stewart at checkpoints to Iraqi soldiers as a Dominican from France. “You didn’t know if the troops were secretly working with terrorist groups. We didn’t trust them,” Michaeel says in a WhatsApp interview from Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan. In summer 2014, while Stewart was briefly back in Minnesota, ISIS captured Mosul and advanced toward Qaraqosh. Michaeel piled manuscripts into trucks and cars and took them to Erbil several times over the next few weeks, including a final load on the night of August 6. “Three hours later, ISIS attacked Qaraqosh,” Michaeel says. Much of the Christian town, including the digitization studio, was looted and burned. But Erbil was a safe haven, and Stewart and Michaeel—last year appointed archbishop of the Chaldean Catholic Church in Mosul—have digitized 1.5 million pages in the ongoing project.

In 2017, Stewart and two colleagues from the HMML were in Timbuktu to digitize medieval Islamic and secular manuscripts compiled by an imam, who had secreted the works in a bunker during Al Qaeda’s occupation of the city five years before. Minutes after checking into the Hotel Auberge du Desert, a walled compound on the road from the airport, the trio found themselves pinned down by a firefight between U.N. peacekeepers and jihadists who had infiltrated the city. The battle continued for three hours, while U.N. helicopters hovered over the hotel. Throughout, Stewart tapped away on his laptop—sending out emails in search of information about what was going on outside. “I never saw him lose his composure,” says his colleague Walid Mourad, HMML field director for the Middle East, Africa and South Asia. Finally, Swedish U.N. peacekeepers arrived in three Humvees and transported the conservators to a secure compound, where they remained for the next two days and nights. “For a couple of nights, back in Bamako, I had bad dreams,” Stewart says.

* * *

Casting his eyes for the first time on the palm leaf manuscripts of Kathmandu, Stewart marveled that so many of them remained intact and legible, despite having been exposed to centuries of dust and moisture, nibbled on by mice and pressed down under the weight of stacks of other manuscripts. “The ancients knew which chemicals to use, how to protect them from insects,” Stewart says. “Even the red dye on the bags they wrapped the manuscripts in served as an insect repellent. They had centuries to get this right.”

But the last major earthquake taught the monk-scholar and his Nepalese colleagues not to take the documents’ survival for granted. “We hope to go back to Kathmandu as soon as possible,” Bhattarai says, with the aim of completing the Asha Archives digitization over the next several years, supported by the Arcadia Fund, a London-based charity. “After that, there are many other libraries, many other private collections. We estimate there are 180,000 manuscripts in Nepal, most of them in the Kathmandu Valley.”

Stewart sees the work as the modern continuation of an ancient tradition. In the Kathmandu library back in 2019, as he turned the centuries-old palm leaves, illustrations of Hindu gods still gleaming on the brittle pages, Stewart was struck not only by the artistry of the works, he says, but by “the miracle of survival.” He realized “how many hands have touched these manuscripts in the process of keeping them safe, across centuries of communal dedication in protecting them.” That fierce dedication to human knowledge, that determination to keep cultural patrimony alive for future generations, has characterized every place he’s worked across the world. “The medium may change,” he says, “but the fact of preserving the word is a constant.”

*Editor's Note, July 27, 2021: A previous version of this story called Gutenberg's print press "the world's first." While Gutenberg's press was the first to lead to mass production of books, wood block printing was hundreds of years earlier in Asia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/f9/cef9b50e-104d-4a3d-bdcd-e676d1c35ffc/mobile_-_opener_-_jun2021_d07_columbastewart.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/18/dc18a7f2-98d1-4119-809e-d27aacb10223/opener-lefttitle-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)