The Secret Codes of Lady Wroth, the First Female English Novelist

The Renaissance noblewoman is little known today, but in her time she was a notorious celebrity

:focal(438x91:439x92)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/2e/d72efa1f-c48b-4a48-9b85-0638e1b97b20/ladywroth.jpg)

Two summers ago, I found myself face to face with a 400-year-old mystery. I was trying to escape the maze of books at Firsts, London’s Rare Book Fair, in Battersea Park. The fair was a tangle of stalls overflowing with treasures gleaming in old leather, paper and gold. Then, as I rounded a corner, a book stopped me. I felt as though I had seen a ghost—and, in a sense, I had.

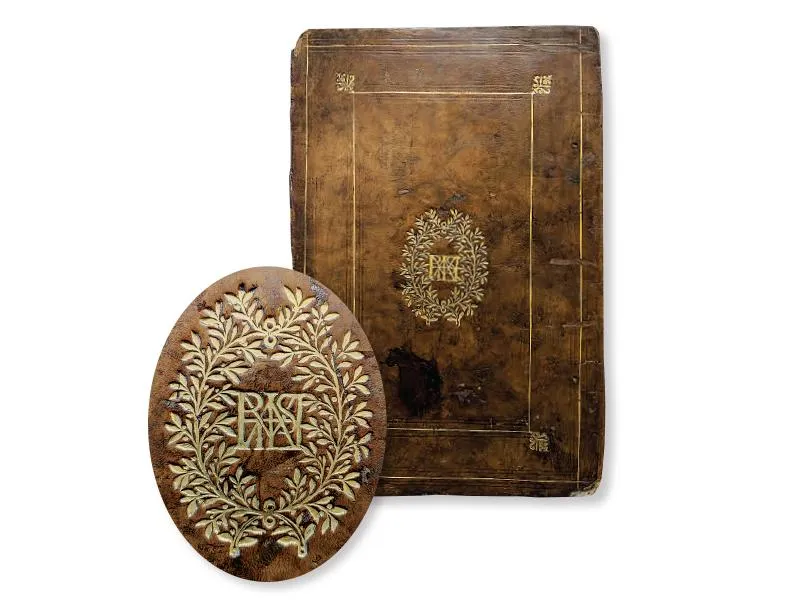

Stamped onto its cover was an intricate monogram that I recognized instantly. It identified the book as the property of Lady Mary Wroth. She was a pathbreaker. A contemporary of Shakespeare in the early 17th century, Wroth was England’s first female writer of fiction. The startling thing about seeing this book was that her house in England burned down two centuries ago, and her extensive library with it; not one book was believed to exist. As a literary scholar specializing in rare books, I had seen a photograph of the monogram five years earlier on the bound leather manuscript of a play Wroth had written that was not in the library at the time of the fire. Now it appeared that the volume I was staring at—a biography of the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great—had escaped the inferno as well.

The monogram was not merely a few fancy initials, although fashionable nobles of Wroth’s period were known to adorn their books, jewelry and portraits with elaborate designs. This was more: a coded symbol, a cipher. It was unmistakable to me. Ciphers conceal meanings in plain sight and require the viewer to possess some secret knowledge, or key, to understand their meaning, one which the creator wants only a few to know. To most people, Wroth’s cipher would look like a pretty decoration.

Little known today, Wroth was notorious in her time. A noblewoman at the court of King James I, Wroth was a published author at a time when the culture demanded a woman’s silence and subservience. Queen Elizabeth I’s Master of the Revels, Edmund Tilney, went so far as to say in 1568 that a husband should “steal away [his wife’s] private will.”

But an author she was. In 1621, Wroth’s first and only printed work caused a scandal. A romance entitled The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, often called simply the Urania, it’s the forerunner of modern novels. At nearly 600 pages, it contains more characters than War and Peace or Middlemarch, and is based largely on Wroth’s own family and acquaintances at court—some of whom were outraged to find their lives and exploits published under a veil of fiction. One aristocrat wrote a scathing invective about the impropriety of Wroth’s work. She fired back, calling him a “drunken poet” who penned “vile, railing and scandalous things” and brazenly challenged him to “Aver it to my face.” Later women novelists, such as Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë and George Eliot, owed a historical debt to Mary Wroth’s 17th-century struggle to be heard.

Perhaps the defining point of Wroth’s life was when she fell in love with a man who was not her husband. He was William Herbert—the dashing 3rd Earl of Pembroke. Herbert had a reputation as a patron of the arts and was something of a cad. In 1609, Shakespeare dedicated his sonnets to “W.H.,” and scholars still speculate that William Herbert was the beautiful young man to whom the first 126 love sonnets are addressed.

Although we don’t know whether Wroth and Herbert’s romance began before or after her husband’s death in 1614, it continued into the early 1620s and lasted at least a few years, producing two children, Katherine and William. Wroth modeled the Urania’s main characters, a pair of lovers named Pamphilia and Amphilanthus, after herself and Herbert.

In the Urania, Pamphilia writes love poems and gives them to Amphilanthus. In real life, Wroth wrote a romantic play entitled Love’s Victory and gave a handwritten manuscript of it to Herbert. This volume, bound in fine leather, is the only other known to be marked with her cipher; designed with the aid of a bookbinder or perhaps by Wroth alone, the cipher must have been intended to remind Herbert of their love, for the jumbled letters unscramble to spell the fictional lovers’ names, “Pamphilia” and “Amphilanthus.”

Wroth’s romantic bliss was not to last. By the mid-1620s, Herbert abandoned her for other lovers. Around this time, she was at work on a sequel to the Urania. This second book, handwritten but never published, sees Pamphilia and Amphilanthus marry other people. It also introduces another character, a knight called “Fair Design.” The name itself is mysterious. To Wroth, “fair” would have been synonymous with “beautiful,” while “design” meant “creation.” Fair Design, then, was the fictionalized version of Wroth and Herbert’s son, William. The story’s secret, hinted at but never revealed, is that Amphilanthus is Fair Design’s father—and that Amphilanthus’ failure to own up to his paternity is why the boy lacks a real, traditional name.

So, too, did William lack the validation his mother longed to see. In 17th-century England, being fatherless was as good as having no identity at all. Property and noble titles passed down from father to son. But William did not inherit his father’s lands or title. Herbert died in 1630, never having acknowledged his illegitimate children with Wroth.

The monogrammed book staring saucily back at me from a glass bookcase that day in Battersea could not have been a gift from Wroth to Herbert: It was published in 1632, two years after his death. I think Wroth intended to give her son this book, stamped with its elaborate cipher, the intertwined initials of his fictionalized mother and father. The book itself was a recent English translation of the Cyropaedia, a kind of biography of Cyrus the Great of Persia, written by the Greek scholar Xenophon in the fourth century B.C. It was a staple text for young men beginning political careers during the Renaissance, and Wroth took the opportunity to label it with the cipher, covertly legitimizing William even though his father had not. To his mother, William was the personification of Wroth’s fair design.

Although Wroth camouflaged her scandalous sex life in a coded symbol, others may have known of her hopes and dashed dreams. William’s paternity was probably an open secret. Wroth’s and Herbert’s families certainly knew about it, and so, in all likelihood, did William. The symbol’s meaning would have been legible to a small social circle, according to Joseph Black, a University of Massachusetts historian specializing in Renaissance literature. “Ciphers, or monograms, are mysterious: They draw the eye as ostentatious public assertions of identity. Yet at the same time, they are puzzling, fully interpretable often only to those few in the know.”

Wroth was a firebrand fond of secrets. She was also an obstinate visionary who lived inside her revolutionary imagination, inhabiting and retelling stories even after they ended. Writing gave her a voice that speaks audaciously across history, unfolding the fantasy of how her life should have turned out. This discovery of a book from Wroth’s lost library opens a tantalizing biographical possibility. “If this book survived,” Black says, “maybe others did as well.”

In the end, the cipher and its hidden meanings outlived its referents. William died fighting for the Royalist cause in the English Civil War in the 1640s. Wroth is not known to have written another word after Herbert’s death. She withdrew from court life and died in 1651, at the age of 63. Sometime thereafter, daughter Katherine probably gathered up some keepsakes from her mother’s house before it burned. They included the manuscript of the Urania’s sequel and William’s copy of the Cyropaedia, which survived to haunt the present and captivate a book detective one day in Battersea. As a student I lacked the means to buy Wroth’s orphaned book. But I told a Harvard curator exactly where he could find it. Today Lady Wroth’s Cyropaedia is shelved in the university’s Houghton Rare Books Library.

Hiding in Plain Sight

In early-modern Europe, ciphers expressed romance, friendship and more. Some remain mysteries to this day

By Ted Scheinman

Paying Court

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/38/113809ac-19db-47cd-beb3-4864faa35965/1.jpg)

Hans Holbein the Younger, the German artist who served in Henry VIII’s court, created this plan for a small shield, likely when the king was romancing Anne Boleyn; the pair’s initials are joined in a lover’s knot. The image appears in Holbein’s Jewellery Book, now in the British Museum.

Greek to Us

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/ea/09ea0e1f-0848-41fa-be8f-7dcecc0bf271/2.jpg)

This cipher—not designed by Holbein—combines the Greek initials of Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, the 17th-century French intellectual and astronomer. It is inscribed on a book by Sir Francis Bacon that de Peiresc gave to his friend and biographer Pierre Gassendi in 1636.

Initial Impression

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/03/9b/039bdf97-1556-452d-9bbb-f3507f4314c4/6.jpg)

Private Lives

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/68/ef689d9c-fed5-4cdf-8f17-91e4320b0d99/7.jpg)

Still Scrambled

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/f1/6af1fad8-ad80-4a58-b256-315ed57632d3/5.jpg)

This design contains the letters “LONHVAYGIMW.” While some Holbein ciphers offer legible acronyms for sentences in French, modern scholars deem this one impenetrable.