Drivers in Dallas earlier this year may have noticed a curious trio of billboards on the side of Highway 67. Instead of advertising for the nearest brisket or “the world’s most refreshing beer,” the signs depicted a black disc ringed by a nebulous, fiery red circle.

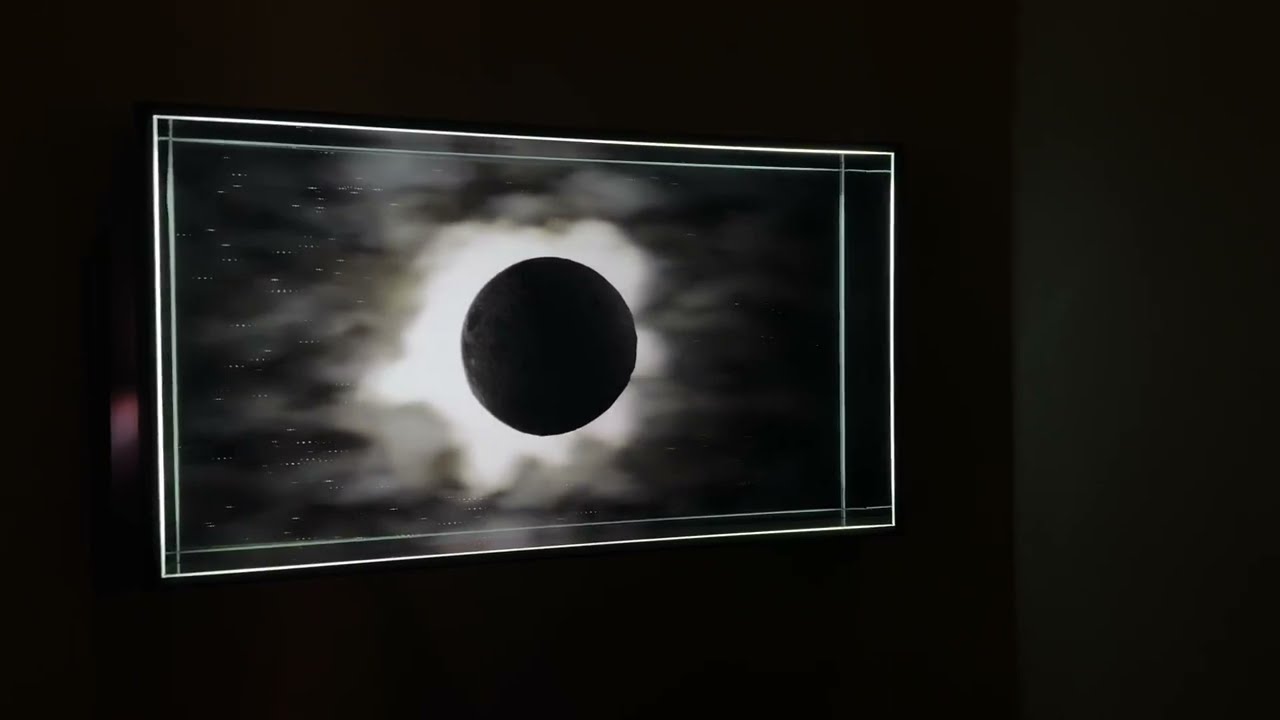

The billboards were actually works of art. They were part of a five-billboard series called View Finder, in which American video artist Brian Fridge portrays a solar eclipse. To create his images, Fridge used a desktop lamp for the sun, an opaque disc for the moon, and a little motor pulling the disc on a string for the gravitational pull that steers the moon around the sun.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/85/09/8509b054-51c0-4728-8c8e-116d904b830e/5_billboard_no5of5_image-2.jpg)

Fridge is one of many artists looking in the shadow of the moon for inspiration, ahead of the solar eclipse set to cross the United States on April 8. At the Dallas Art Fair, Ashley Zelinskie will unveil an eerie sculpture depicting a bitumen-black moon cloaking a tentacled sun, plus a hologram of a floating black moon. Meanwhile, in New York City, Angela Lane, who has been creating postcard-sized oil paintings depicting eclipses, twin suns and other celestial phenomena for almost a decade, will present another exhibition of such paintings at the gallery Anat Ebgi later this year. And at her solo show at Hollis Taggart, Rachel MacFarlane will display The Event, a fantastical depiction of hurricane-battered Prince Edward Island in Canada that is coupled with an abstract depiction of a solar eclipse to imbue the landscape with a sense of foreboding. MacFarlane is also planning to view the upcoming eclipse, then rebuild the scene from memory back in her New York City studio.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a3/41/a3418602-747c-427e-97af-dfa541b518bb/rachel_macfarlane_-_htg19358_-_4000.jpg)

That the solar eclipse has become a favorite muse for artists isn’t all that surprising considering the theatrical allure of the phenomenon. What is remarkable is just how long artists have tried to make sense of the celestial event, and just how much their interpretations have evolved with our own understanding of eclipses.

“I think it brings us, in a visceral, time-limited way, in touch with these cosmic-scale things that really pull us out of ourselves and our own, little, tiny world and bring us into some kind of interface with the infinite,” says Karl Kusserow, a curator of American art at the Princeton University Art Museum who contributed to a 2017 exhibition about eclipses called “Transient Effects.” “Eclipses have been happening for billions of years, and they engage us, in a very fundamental way, with that ineffable hugeness of the world beyond our daily routines.”

As it happens, the cyclical occurrence of a total solar eclipse (which, contrary to popular belief, isn’t all that rare and happens every 18 months or so somewhere in the world) makes this extraordinary phenomenon an ideal platform to explore the changing ways that humans perceive the world around them. These perceptions vary based on geography and culture, but also on time.

The solar eclipse hasn’t always been the entertaining tourist magnet it promises to be on April 8, when the path of totality will extend from Mexico, across the United States from Texas to Maine, and into Canada. People didn’t flock to rooftop viewing parties. They didn’t travel thousands of miles to watch the sky go dark. To ancient civilizations, an eclipse was seen as a dark omen that often signified the wrath of their gods. It wasn’t exhilarating; it was unsettling.

This might explain why, according to some experts, the solar eclipse wasn’t depicted much in the early days. In many ancient cultures, the sun was seen as a deity and a source of life that helped the crops grow every season. By the same token, the absence of a sun was fraught with danger—so why turn it into art?

“To make an illustration was not as easy as just picking up a ballpoint pen,” says Kusserow. “If you’re carving in stone, you’re going to focus on things that are not the worst of all times.”

Early depictions of the solar eclipse are few and far in between, but they do exist. In Norse mythology, the eclipse takes the form of two wolves—Skoll and Hati—chasing the sun and the moon. The story goes that if one of the wolves caught the sun, and a solar eclipse occurred, it would bring about the end of the world. And in Chinese mythology, the eclipse has often been depicted as a dragon devouring the sun.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/23/f523fa03-b997-45a9-9699-fca0bc0e50ea/lane_eclipse_after_image_2021_al1011.jpg)

In Western art, one of the most recurring representations of the eclipse has been in Christian art. But as the director of London’s Science Museum, Ian Blatchford, thoroughly outlines in a 2016 article in a Royal Society journal, there, too, the eclipse is more of a symbol than a literal depiction.

For example, the crucifixion was believed to have taken place during a total solar eclipse, so the Salerno Ivories from the 11th or 12th century show the dying Christ flanked by the sun and the moon, hinting to a verse from the Bible stating that “darkness fell over the whole land … because the sun was obscured.” In the Echternach Gospels, which illustrate the moment of Christ’s death on the cross, the sun and the moon take the form of human figures shrouding their faces in grief.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9b/3b/9b3b4e3b-696f-4351-8103-fc3e52fe8fd6/isaac-and-rebecca-spied-upon-by-abimelech-1519.jpg)

Depictions of eclipses became more and more realistic during the Renaissance, a period known for its convergence of art and science. Around 1518, Raphael and his workshop created a striking fresco titled Isaac and Rebecca Spied Upon by Abimelech. Located in a loggia at the Vatican Palace, the fresco features a detailed version of a solar eclipse, including the sun’s fiery streamers. Some experts believe that Raphael used the eclipse as a complex metaphor for Isaac and Rebecca’s stealthy deception and lovemaking, which occurred during totality.

In more recent years, various artists have explored celestial themes with increasing detail—from Etienne Trouvelot’s captivating astronomical drawings (1878) to Roy Lichtenstein’s cosmic pop art (1975). But the most important among them remains the early 20th-century painter Howard Russell Butler, whose eclipse paintings stand out both for their artistic and scientific merit.

Butler is most famous for his portraits of Andrew Carnegie, but he studied physics and law before turning to art. When the painter was 62 years old, he was invited to join a U.S. Naval Observatory expedition to Oregon, where he chronicled the 1918 solar eclipse. “I generally asked for ten sittings of two hours each,” he later wrote of that expedition. “But all the time they would allow me on this occasion was 112 1/10 seconds.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e7/00/e7002b95-fdb7-4d69-8cff-0a97c5fbae20/pp357.jpg)

Butler would go on to paint three different eclipse paintings after observing the phenomenon in 1918, 1923 and 1925. By that time, photographers had attempted to document the eclipses with varying levels of success. But where photographers had struggled to capture the nuances and fiery hues of the sun’s corona, Butler succeeded by taking meticulous shorthand notes during the eclipses, then filling in the gaps later, a bit like a paint by numbers kit. (By some accounts, Butler had mastered this technique while painting 13 portraits of Carnegie, who reportedly could not sit still for long.)

Today, capturing a solar eclipse is no longer a herculean effort. Almost anyone with a digital camera, a solar lens filter and the patience to read explainers online can get a decent photo of it. The event has been documented in all its evanescent glory, and from every single angle. Yet, artists continue to be enthralled by it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/90/619075a4-7c73-41df-9bc5-e006454ea55b/eclipse3.jpg)

For visual artist Zelinskie, to make art that is inspired by science means to grapple with existential questions like “Why are we here?” and “What’s out there?” “We’ve been asking these questions since we were able to think, so to be answering these questions as an artist is basic human curiosity,” she says.

A little over two years ago, Zelinskie partnered with NASA scientists to produce a range of artworks, like a pair of marble gloves modeled after retired NASA astronaut Mike Massimino’s hands. This year, she’s unveiling Eclipse, a 3D-printed sculpture that doubles as a pinhole viewer, plus a hologram of the event. “[The solar eclipse] is something you have to see for yourself. You can’t describe it to somebody,” she says. “That’s why I chose to make a hologram of it. People see the hologram I’m making and take photos of it, but it doesn’t look right; you can’t tell that it’s 3D, and that’s the perfect medium.”

“It’s something you have to physically be there for,” she adds.

For her sculpture Eclipse, Zelinskie tried to convey the eerie feeling that washes over during a solar eclipse. “The birds freak out, the crickets come out, the animals think it’s nighttime, there’s a weird lighting situation,” she says. Zelinskie fashioned her moon using data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been mapping the lunar surface for 15 years. She then sheathed the sphere in a dark black patina, and she 3D-printed flares to represent the corona.

The resulting sculpture is somewhat sinister, which goes back full circle to the dawn of eclipse art. “Every culture has eclipse artwork, but it’s always, ‘God is punishing us,’” says Zelinskie. “I didn’t find one instance of, ‘Yay, an eclipse.’ I guess this is how humanity is interpreting it, so I’m staying true to that doom and gloom.”

Meanwhile, video artist Fridge has long been fascinated with light, matter and the passing of time, but his View Finder series marks the first time that he has made eclipse-inspired artwork. Fridge is known for his abstract images and films depicting natural processes that he records in his home—like seeded clouds he created in his own freezer or, in this case, desktop lamps that stand in for the sun. “I never really leave the house, and I don’t record anything outside in nature,” he told me on a recent video call from his house, which is also his studio. “I find things on the domestic scale, then try to imbue some kind of meaning to it.”

To make View Finder, Fridge used a little device that plugs into an iPhone to pick up the heat signature of any given object and create what is known as thermographic imaging. He created a six-minute film retracing the evolution of his makeshift eclipse, captured stills from various stages of an eclipse, then blew them up to fit the size of five billboards in and around Dallas.

The result was convincing enough that when the film, also titled View Finder, premiered at Dallas Contemporary on March 10, Fridge felt the need to clarify this wasn’t footage from “the actual thing” as some viewers had assumed. It was an artistic interpretation, an illusion that was intentionally created with the constraints of household objects. “I like the meaning that could come from something that’s this limited, and you feel those limits,” he says, referring to the highly realistic renderings one can achieve with a computer or artificial intelligence today.

With View Finder, Fridge says he wanted to explore different ways in which humans see things. You can don a pair of safety glasses and look up at the solar eclipse, or you can drive past a billboard on the side of a highway and find meaning in a still image.

“Hopefully that would do what art does,” he says, “which, to me, is to contribute to a sense of curiosity and wonder, and hopefully more complex and diverse ways of seeing the world.”

:focal(1218x690:1219x691)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/1c/6b1cfcc8-f8af-4174-bb06-ed982d24b719/viewfinder_still_1_cmyk_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Elissaveta_M._Brandon.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7f/e7/7fe705ec-c849-4462-a4c2-3ea96cb5a7d6/banner_eclipse-merch_1000x500_mag.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Elissaveta_M._Brandon.jpeg)