Audrey Flack laughed when remembering that painter Alice Neel called her a whippersnapper in the 1970s. Just after celebrating her 90th birthday in 2021, far from a whippersnapper, Flack—a pioneering photorealist painter, sculptor of monumental bronze, and an artist whose works are in the collections of museums ranging from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) to the National Gallery of Australia—saw no end to her creativity. “Titian made art into his late 80s, and I’m now past that. I always wanted to paint like an old master, or rather an old mistress,” she told me. “A radical contemporary old mistress.”

Until the day before she died last week at 93, Flack—until then one of the oldest living first-wave feminist artists—still feverishly worked in her Upper West Side studio, realizing her passion for dizzying color and intense realism, often engaging the female experience. “I have many, many projects in my head,” the nonagenarian said as we sat in her home studio, which overlooks the Hudson River. (In my profession as an art historian, I have been writing about Flack for nearly 20 years; we remained close up until her death.) She showed me her rainbow-infused portrait of Camille Claudel, an accomplished sculptor in her own right as well as being a model and lover to Auguste Rodin. “It’s so finite. I’m 90. There’s no holding back.”

Over the next three years, Flack’s creativity surged. This March, her one-person exhibition of 16 new works premiered at the Hollis Taggart Galleries in New York to great acclaim. The opening also served as a book launch for Flack’s memoir, With Darkness Came Stars, which the New York Times described as “something to savor.” Hundreds of fans braved a rainstorm, in a line that ran out the front door of the gallery, only to stand shoulder to shoulder to have Flack sign copies. Just last week, she completed a commission of a larger-than-life-size bronze statue of Adrienne de La Fayette for Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. A solo exhibition, “Audrey Flack NOW,” opens in October at the Parrish Art Museum on the eastern end of Long Island.

Mindful of her legacy, Flack in recent years donated her personal papers to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, the world’s largest repository for documentation about American visual art. “This significant collection of the papers of Audrey Flack provides an extraordinary prism through which we can examine the historical and personal context of her life and work,” said Liza Kirwin, who at the time of the donation was the Archives’ interim director. Flack made an initial donation of her papers beginning in 2009, and a voluminous archive of project files, writings, notes, videos and photographs arrived in later years. The collection, said Kirwin, is “a remarkable body of work that speaks to Flack’s experience as a photorealist painter, sculptor, feminist, mother and powerful sorceress, who reimagined, redeemed and recreated archetypal and mythical images of women.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/5d/495db4db-05c5-4805-8add-82904c8b51f2/flackanddekooninghigherres.jpg)

When I visited her studio in 2021, Flack had been busy mining for correspondence, old catalogs and exhibition lists, and photographs dating back to the 1940s for the donation. Among a clutter of paint jars, scattered colored pencils and drawers jam-packed with works on paper, she rediscovered a 1980 photograph, taken during a visit to the studio of the abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning. De Kooning, who famously depicted women with a brutal, aggressive brushstroke, still intrigued Flack for his energetic paint handling.

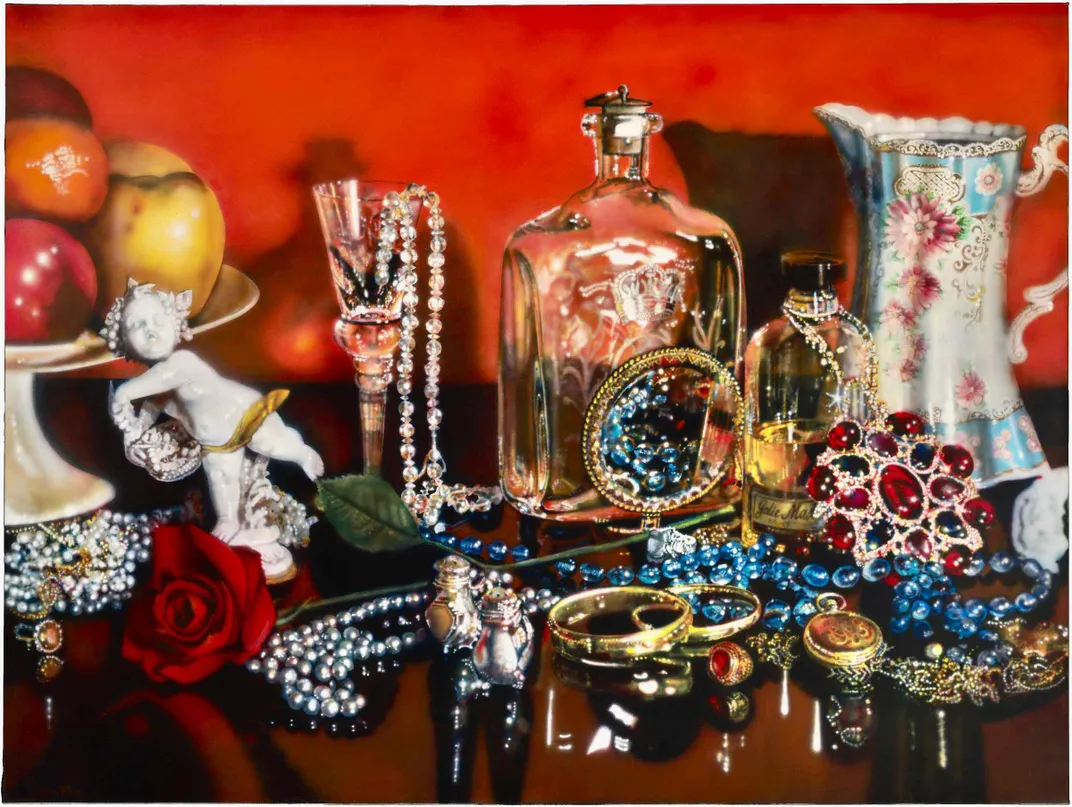

The sole woman among the original photorealists of the 1970s, Flack made enormous paintings plumbing personal and sociopolitical issues, stereotypes of womanhood and the transience of life. Her male peers tended to coolly render neutral subjects such as cityscapes and cars. Flack, who boldly renounced her abstract expressionist training with Josef Albers at Yale University, found herself especially attracted to sensual pleasures—succulent fruit, luscious desserts and shimmering jewels crowd the flawless surfaces of her ambitious canvases.

Based on configurations of intimate objects arranged by Flack in her studio and then photographed, her first monumental photorealist still life, the 1972 Jolie Madame was executed with both underpainting and airbrush from a slide projected on a canvas. The 6-by-8-foot painting celebrates traditional objects associated with femininity and female beauty. Glistening jewelry and the perfume bottle that lends the work its title reflect off a smooth dressing table, like sun on quiet water. Soon after its completion, Jolie Madame appeared at the New York Cultural Center in “Women Choose Women,” the first large-scale exhibition organized by women and only showing art by women.

Leafing through a binder of old negatives, slides and photographs, Flack discovered a snapshot from 1993. She poses with 16 other photorealists, all male, and one other woman, Susan Meisel, the artist and wife of the leading photorealist art dealer Louis Meisel, who is also pictured. That memento calls to mind the famous Life magazine photograph of Hedda Sterne, the lone woman standing with her abstract expressionist cohort. The first photorealist work MoMA ever acquired, however, was not made by any of the men in the photo. Rather, Flack holds that honor. The museum purchased Flack’s 1974 six-foot canvas Leonardo’s Lady the year after it was painted.

Flack’s paintings depicting a cornucopia of pleasures were not always appreciated by critics. The New York Times critic Hilton Kramer labeled her as “the brassiest of the new breed … the Barbra Streisand of photorealism”—an aspersion that stung to the very end.

Undeterred by sexist reviews, Flack remained incurably and proudly committed to her feminine and feminist subject matter.

Believing that she had exhausted the possibilities of photorealism, in the early 1980s Flack surprised the art world by abandoning painting in favor of sculpture. She executed larger-than-life-sized indoor and outdoor bronze sculptures of female goddesses, including Athena, Daphne and Medusa, along with invented deities. Always pushing against the standard, Flack offered these women as strong heroines rather than objectified figures. One major public commission is her allegorical Civitas group of four 22-foot-tall statues, which serves as a commanding monumental gateway to Rock Hill, South Carolina.

When working on a large scale, Flack would retreat to her spacious studio in East Hampton, New York. A 2017 7-by-7-foot canvas, her first mural-sized conception in 30 years, riffs on Peter Paul Rubens’ exuberant 17th-century painting The Garden of Love. In Flack’s reworking, a comic book-style Superman and Supergirl break through glass sprinkled with gold glitter and lined with gold leaf as they enter Flack’s reinterpretation of Rubens’ Baroque composition. Those shards of glass signal the breaking of artistic barriers, the breaking of the glass ceiling, the entering of light and—idealistically—a new era of female equity.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/ac/49acdb5f-b085-4d83-8892-93094890ba7f/flackfiatluxe2017.jpg)

Interested in “reclaiming the Madonna,” Flack had been envisioning a multimedia solo exhibition with that title in the years before her death. “Jews don’t have a compassionate mother,” said Flack, born in New York to immigrant, Eastern European Jewish, Yiddish-speaking parents. “In the Jewish tradition we have strong women like Rachel and Leah, but we don’t hear much about their mothering.”

On one of my visits to her studio, she had me pose for an in-progress bust of the Virgin Mary. For nearly an hour Flack modeled the clay and eyeballed the measurements of my cheekbones and nose. While I sat still and silent, Flack sculpting with my face as her guide, she explained why she was especially moved by Mary’s relentless anguish. Flack viewed Mary as a Jewish mother whose despair over the death of her son embodied the grief she herself felt as a mother of an autistic child who never learned to speak. Flack said, “Mary in art screams silent screams of agony. I’m sort of Mary. A woman of sorrow for my sorrow.”

She planned to make more images of Mary, a figure she painted several times in the early ’70s, including Macarena of Miracles (1971), which was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A painting shown at Hollis Taggart was part of that ongoing project: a 2022 tour-de-force self-portrait of Flack in the position of the Virgin Mary pictured as a medieval icon.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/28/69/28690f01-d89e-4546-9339-bc720d7a8d54/flackamericanathenahighresoption2.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ce/7c/ce7c419c-50a3-4428-82b4-a5c20a47a441/flackmacarenaofmiracles1971.jpg)

Flack’s versatility and exuberance for new forms of creative expression took her to banjo camp in the summer of 2005. She became an accomplished banjo player who could frail and claw hammer with the best of them. Following her newest artistic muse, Flack formed a group, Audrey Flack and the History of Art Band. Lead vocalist, banjoist and lyricist, Flack wrote playful songs about art-related subjects and artists—among them Rembrandt, van Gogh and Mary Cassatt—set to old-time bluegrass melodies. An album was released in 2012.

A sampling of Flack’s lyrics for a song about Cassatt, one of a handful of female artists finally featured in the third edition of H.W. Janson’s longtime standard art history textbook, offers a case history for the plight of women artists:

Mary never got married

Stayed single all her life

She’d rather paint and sketch and draw

Than be somebody’s wife …Because she was a woman

It took a lot more time

To have her work be recognized

Even though it was so fine.A genius of the highest kind

We now know her to be

Mary Cassatt oh Mary Cassatt

You now made history!

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/d2/d4d2a0cc-ac1d-4a1c-a64d-d0af3a1443fb/flackwithbandinfrontoftimetosavejpg.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/cd/66cd4408-9fda-4940-a89d-7152d0c50b11/flackwithphotorealists1993.jpg)

So too, Flack made history. While Cassatt is among the first cadre of woman appearing in Janson’s volume, Flack was among three then-living female artists to have their art in that revised text. She was rightly proud of this recognition and even more so because she navigated a successful art career while raising two children, mostly as a single mother. Last year, she endowed an eponymous fellowship at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) that is earmarked for researchers whose personal circumstances, including the caregiving responsibilities that challenged Flack, preclude them from participating in longer-term residencies.

Flack’s walk down memory lane was not without its challenges. She unearthed a typed letter on onionskin paper that she wrote in the late 1970s to art critic Vivien Raynor, who dubbed Flack’s work in a painful New York Times review as “horrendous” and chastised the “vulgarity of her literal mindedness.” Flack passionately defended her art—purposefully narrative in intent, meticulous in technique and meant as a rejoinder to what she viewed as an elitist art establishment dominated by abstraction. “The literal mindedness in my work that you refer to, is quite intentional, designed to reach an audience larger than the immediate art world … an audience that has been ignored and intimidated for many years.”

SAAM recently acquired her 1976 Queen, one of many canvases that daringly and unfashionably rejected abstraction in favor of a more humanist-centered art. ”Queen is the iconic photorealist painting and simply stops visitors in their tracks at SAAM, just like paintings by Albert Bierstadt, Georgia O’Keeffe and Nam June Paik’s video installation,” says Stephanie Stebich, the museum’s director. “Flack shook up the art world. She was a trailblazer who will continue to be a beacon for the next generation of artists.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/04/00/04005304-5cf4-4bc9-be4f-372b43ce55ab/audreyflacksstudio.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/f4/6bf4818a-1500-431d-9e91-3d36e3816e07/saam-2022115_1.jpg)

Flack always idealistically believed in the power of art to heal and tender hope, the running theme of her poignantly confessional memoir. Fifty years ago, she delivered the commencement address at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The utopian vision she shared with the graduates guided her groundbreaking, magical art and life: “Great art is in exquisite balance. It is restorative. I believe in the energy of art, and through the use of that energy, the artist’s ability to transform his or her life, and by example, the lives of others.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/46/66465d89-db2b-489b-bd84-1146c878bd16/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/69/6e69bfb3-8248-43f6-83ab-b61e32ba0770/social-media-dimensions.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HeadshotSmithsonianBaskind_2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HeadshotSmithsonianBaskind_2.png)