Reaching Out to Those Behind Bars

Learn how the Anacostia Community Museum redesigned its acclaimed exhibition “Men of Change” as a digital offering for incarcerated audiences

:focal(1990x668:1991x669)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/We_see_you_we_care.jpg)

What happens when people can’t visit a museum? You have to bring the museum to the people! This is the attitude our staff took in order to stay relevant to our audiences during the pandemic. The biggest project we undertook during this challenging year was redesigning an indoor exhibit called Men of Change so that it could live outdoors in Washington, D.C. Ward 7’s Deanwood neighborhood.

With this simple change in location came an unexpected “a-ha” moment. We discovered audiences that may never have connected with us during normal times – pedestrians on their way to the Metro, students on their way to school, or neighbors picking up free meals at the Recreation Center. But the most surprising new audience was the population of local residents incarcerated at the D.C. Jail several miles away from Deanwood.

The discovery happened through a partnership with the D.C. Public Library (DCPL) – one of the onsite hosts of our reinvented exhibition Men of Change: Taking it to the Streets. In making plans for the exhibit launch, we learned of their satellite library within the walls of the D.C. Jail. During non-pandemic times, librarians provide books to jail residents who can check them out. But this program had been temporarily cancelled due a heart-breaking situation. To stop the spread of COVID, incarcerated residents of the jail had been placed on twenty-three hour/day lockdown and all enrichment programs had been cancelled – including book lending.

During the pandemic, people across the world felt confined in their homes – but perhaps none more so than those incarcerated in our prisons and jails. DCPL told us of one accommodation the city had given the jail residents to help alleviate tension – 1,000 digital tablets loaded with education content, e-books, and a messaging system to the outside world. With the 300 tablets previously owned by the jail and the newly acquired 1,000 devices, this meant that DCPL was able replace their book program with digital media and serve almost every incarcerated individual in the facility.

This gave us an idea. We wondered if we could somehow get Men of Change onto these tablets at the jail to provide a sort of message in a bottle for these folks who were hurting. In some small way, we could say “We see you. We care.” Men of Change features powerful stories of more than two dozen Black male leaders throughout American history. According to the D.C. Department of Corrections, the local incarcerated population is 86% African American and 97% male. The content of the exhibition was perfect – inspiring stories, quotes, and photos of Black men from all eras who found cracks in a system designed to hold them back. Maybe the exhibit could provide a bit of encouragement during an incredibly frustrating time.

If we could reinvent this exhibit for the streets, could we reinvent it again in digital form? The exhibition, which was created by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, already had a website, but we needed a product that didn’t depend on internet access. We settled on the idea of creating a video tour of the exhibit using voices from the Deanwood community. We wanted to help the jail residents go on a field trip in their minds – to imagine themselves taking a walk through the neighborhood, seeing African American strength through generations, in a city that looks familiar.

By mid-May 2021, we were finally able to upload the Men of Change video tour onto jail tablets – along with a recommended reading list, a PDF of all the exhibit text, and a Spanish language version of the video.

The existence of these tablets gave us a portal to reach men and women that we never had access to before. These individuals were incarcerated just three miles from the museum. This made me wonder what else we can do to reach this community that many cultural institutions have forgotten.

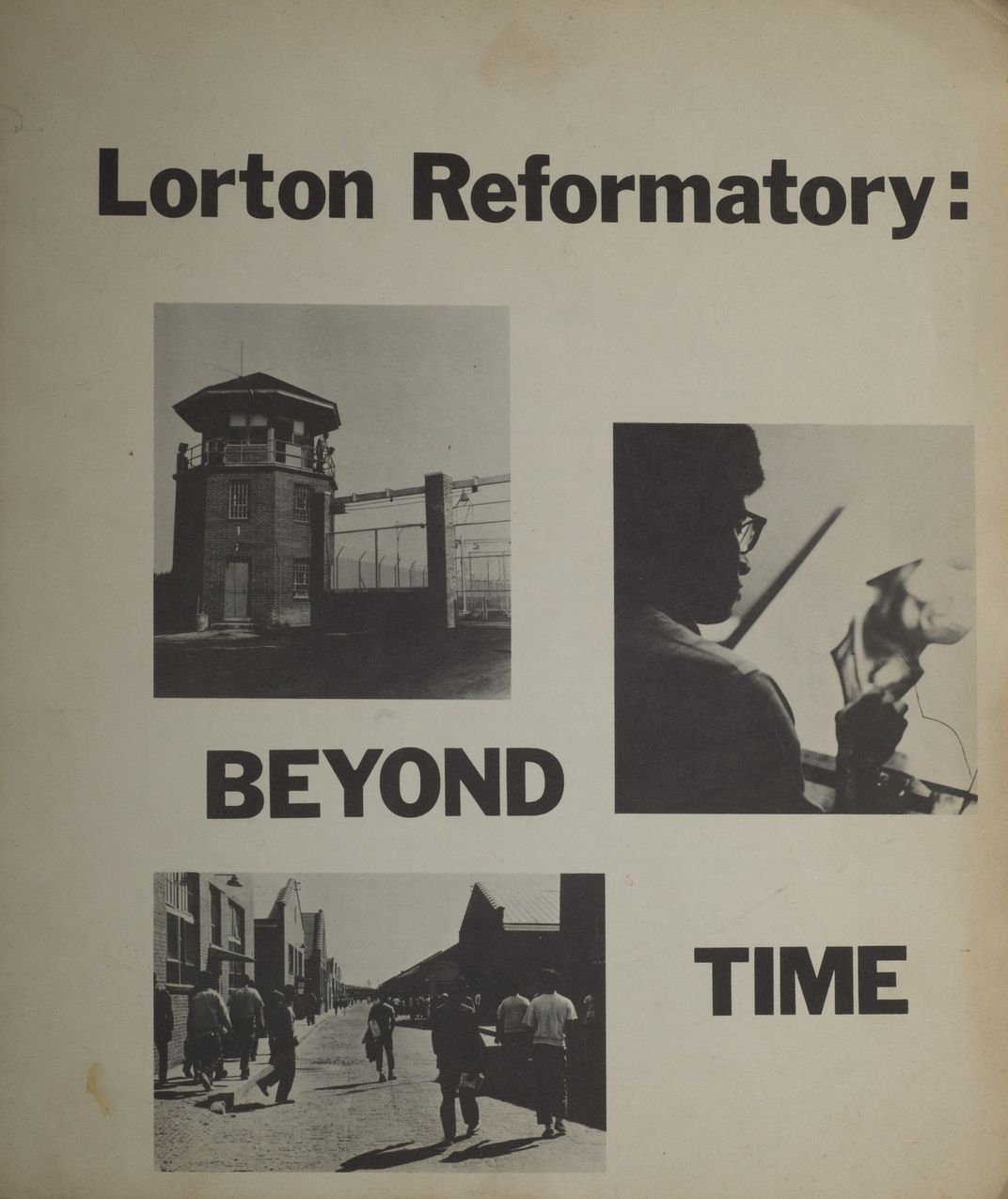

What place do museums have in a world behind bars? I turned to our museum archives for inspiration. I thought to myself, “This is exactly the kind of question our founder, John Kinard, would ask.” Sure enough, he and museum staff had forged this path back in 1970. In a ground-breaking exhibit, the museum brought to Smithsonian audiences a very earnest and realistic portrayal of the daily life at the old Lorton Reformatory in Fairfax, Virginia. Lorton, a federal prison for D.C. offenders, closed in 2001.

Embodying the spirit of our museum that still lives on today, the exhibit Lorton Reformatory: Beyond Time was created – not just about incarcerated men – but with them. The museum hoped that by showing the creative spirit and true humanity of those behind bars that society could better understand their needs for new services. Special arrangements were made for incarcerated residents to perform concerts for museum visitors and to hold meaningful community discussions about prison reform. Kinard had effectively redrawn the boundaries of the community his museum was to serve.

The exhibit brochure states:

“A discussion on the causes of crime, on the meaning of justice and penal reform is of paramount importance to all of us. After all, our concern is not for strangers, unknown to us, but for our neighbors-for those related to us by blood and marriage-in a word-our concern is for our brothers.”

- Zora B. Martin, Assistant Director, Anacostia Neighborhood Museum

These words seem more relevant now than ever.

It makes me proud to know that the spirit of the original Anacostia Neighborhood Museum (as it was called then) is still with us today – fifty years later. Our revolutionary roots are there to remind us to push the boundaries of what museums can do for those whose stories are often untold.

Just as the country is opening back up, the D.C. Jail too lifted the lockdown – just two weeks ago. All reports seem to indicate that jail residents will not lose access to the tablets that became their lifeline during the pandemic. Likewise, the Anacostia Community Museum will not lose the inspiration to look past the walls of its building – to take the museum to the people, wherever they reside.

Men of Change: Taking it to the Streets will be open in Deanwood until August 31, 2021. (4800 Meade Street NE, Ron Brown High School). A companion audio tour is available. The Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum reopens to the public on August 6, 2021 featuring the exhibition, Food for the People: Eating & Activism in Greater Washington. Located at 1901 Fort Place SE, the museum hours will be Tuesday-Saturday 11 a.m.-4 p.m. More details are available at https://anacostia.si.edu.

An abbreviated version of this article was originally published via the Washington Informer on July 5, 2021. Read the original version here.