What Do WALL-E and Salvador Dalí Have in Common? Meet DALL-E 2

This new and improved A.I. system can produce photorealistic images of anything on demand

:focal(621x627:622x628)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bf/09/bf098e6b-daff-4a00-a5f6-3d3c209b10cd/screen_shot_2022-04-08_at_15023_pm.png)

Imagine typing this phrase into a blank computer screen: “a bowl of soup that looks like a monster.” A few seconds later, a creature knitted out of wool—and bathed in soup—could be smiling at you.

Perhaps it’s an “Andy Warhol style painting of French bulldog wearing sunglasses” you are after, or “polymer clay dragons eating pizza in a boat.” If you can dream it, DALL-E 2 can create it.

In January 2021, artificial intelligence lab OpenAI created DALL-E, a neural network that generates cartoonish images from text captions. Now, just over a year later, DALL-E 2 has arrived, with a faster system that delivers more realistic compositions in higher resolution.

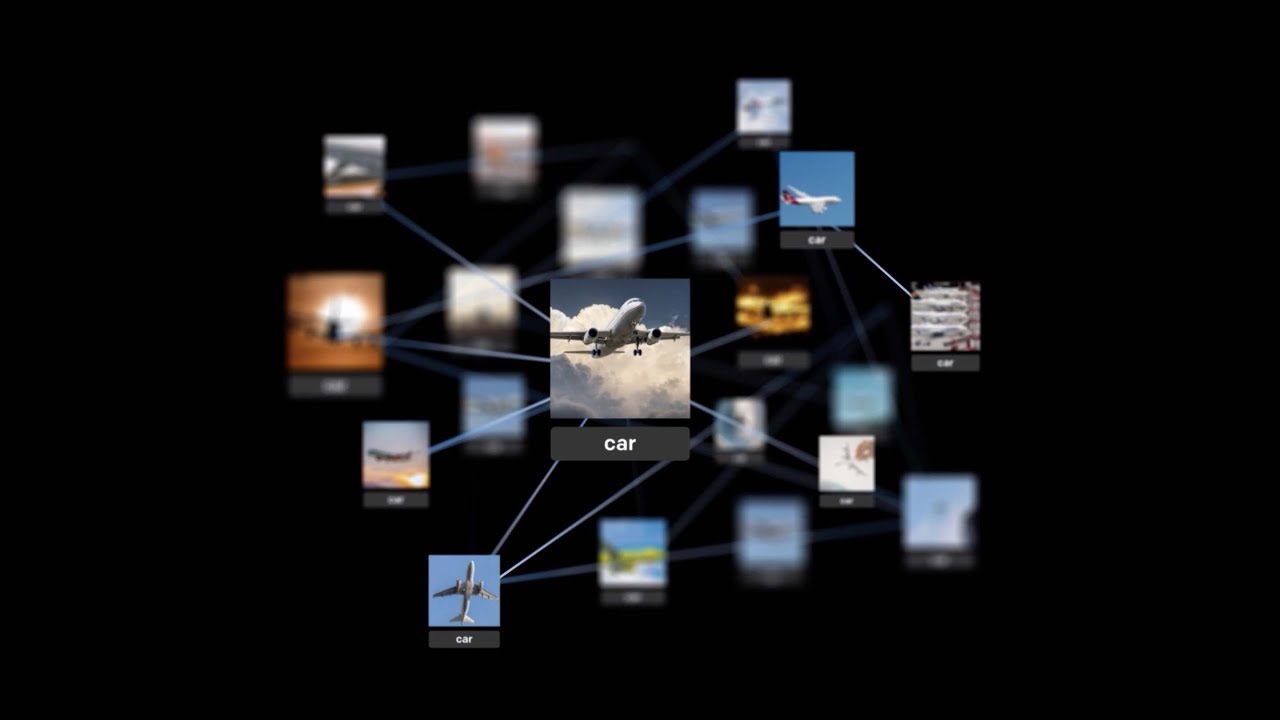

Merging the names of robot WALL-E and artist Salvador Dalí, DALL-E 2, like its predecessor, was trained to learn the relationship between images and the text used to describe them. The new technology, however, works thanks to a process called “diffusion.” Basically, the system reorganizes a random pattern of dots into an image as it recognizes specific aspects of the figure.

Alex Nichol, one of the researchers in charge of developing DALL-E 2, recently walked Cade Metz, a technology correspondent with the New York Times, through a demonstration. When he typed “a teapot in the shape of an avocado,” the A.I. produced ten different images of an “avocado teapot”—pitted and unpitted. In a series of experiments, Nichol showed off DALL-E 2’s ability to edit images. He asked for “a teddy bear playing a trumpet underwater,” and the resulting image dutifully included little bubbles coming out of the instrument. Nichol then erased the trumpet and, with a simple command, swapped in a guitar instead.

Editing is a distinct upgrade from the original DALL-E, reports Adi Robertson for the Verge. With a feature called inpainting, users can add or remove elements from an existing image, she explains, and another feature—variations—makes blending two pictures together possible.

The first iteration was based on GPT-3, a model created by OpenAI that predicts the next words in a sequence. In the case of DALL-E, it anticipates pixels instead of words. DALL-E 2, however, uses CLIP, OpenAI’s neural network, or mathematical system modeled on the network of neurons in the brain, according to Engadget’s Andrew Tarantola. This technology is trained with a variety of pictures and natural language available on the internet. For instance, by looking at patterns in thousands of bear photos, the system learns to recognize a bear.

CLIP translates a text command into an “intermediate form” that captures the traits critical to any image that meets the command’s requirements, reports Will Douglas Heaven of MIT Technology Review. Then, another type of neural network called a diffusion model actually generates an image with these features. “Ask it [DALL-E 2] to generate images of astronauts on horses, teddy-bear scientists, or sea otters in the style of Vermeer, and it does so with near photorealism,” writes Heaven.

That said, DALL-E 2’s technology is not entirely without flaw. Occasionally, it can fail to recognize what is being said. For instance, when Nichol asked it to “put the Eiffel Tower on the moon,” it put the moon in the sky above the tower, per the Times.

Other than imperfections in its automation, DALL-E 2 also poses ethical questions. Although images created by the system have a watermark indicating the work was A.I.-generated, it could potentially be cropped out, according to the Verge. To avoid potential harm, OpenAI is releasing a user policy that forbids asking the system to produce offensive images, including violence, pornography or political-themed messages. Additionally, users will not be allowed to ask the A.I. to make images of recognizable people based on a name to prevent abuse.

The tool isn’t being shared with the public yet, but researchers can sign up online to preview the system. OpenAI plans to eventually offer the technology to the creative community, so that people such as graphic designers can use new shortcuts when developing digital images, per the New York Times. Product designers, artists and computer game developers could find it to be a useful tool too, reports Jeremy Kahn of Fortune.

“We hope that tools like this democratize the ability for people to create whatever they want,” Nichol tells Fortune.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anto.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anto.png)