The Seesawing History of Fad Diets

Since dieting began in the 1830s, the ever-changing nutritional advice has skimped on science

:focal(1061x707:1062x708)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cf/dd/cfdd13dc-dc0a-46c4-ac6f-efc320af7a6c/gettyimages-589153824.jpg)

Each year, 45 million Americans go on a diet, and while their end goals may be similar, the paths they take to get there can look vastly different depending on the latest conventional wisdom.

The United States seems to undergo dietary whiplash every decade or so, and it has been that way since the inception of dieting in the 19th century. “What is striking is just how little it takes to set off one of these applecart-toppling nutritional swings in America,” wrote Michael Pollan in “Our National Eating Disorder,” in a 2004 issue of the New York Times Magazine. “A scientific study, a new government guideline, a lone crackpot with a medical degree can alter this nation’s diet overnight.”

Dieting in the U.S. began in earnest in the 1830s, with the emergence of Sylvester Graham, a Presbyterian minister who was strident about the hazards of eating processed flours and who developed one made from the entire wheat germ, not just the endosperm.

Over the decades—and centuries—that followed, all manner of food and fitness regimens and pills, potions, and pastes have been touted as the magic bullet to beauty, fitness and svelteness. Adherents to various diets have engaged in floor-rolling—literally rolling on the floor; taken baths with thinning salts; subsisted on little else but bananas and skim milk; and voluntarily undergone yogurt enemas.

In 1863, English undertaker William Banting went on a low-carb diet to lose weight and wrote about it in his booklet “Letter on Corpulence.” It became so popular in both the United Kingdom and America that his name became a verb: The response to, “Would you like a piece of cake?” was, “No, thank you, I’m Banting.”

The early 20th century saw the advent of the “reducing salon,” at which clients would be enveloped between two sets of rollers that would—through the power of electricity—squeeze up and down the body up to 80 times per minute.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cc/04/cc04a236-7037-4f36-a767-9a759d3746b5/fad_diets.jpg)

In the 1920s, John Harvey Kellogg—at what Pollan calls his “legendarily nutty sanitarium” in Battle Creek, Michigan—prescribed an all-grape diet and “a two-fronted assault on his patients’ alimentary canals, introducing quantities of Bulgarian yogurt at both ends.”

The following decades saw the rise of the grapefruit diet (1930s), which promised weight loss if a grapefruit was eaten at each meal; the cabbage soup diet (1950s), which allowed the indulgence in as much cabbage soup as one could consume; and the macrobiotic diet (1960s), based on a Japanese diet of soy, brown rice and vegetables.

Weight Watchers, which came along in 1963, encouraged Americans to eschew “dieting” and embrace “eating management,” but the faddists did not disappear entirely. By the end of the decade, the 3-Way Diet Program claimed to “LITERALLY MELT THE FAT OFF YOUR BODY LIKE A BLOWTORCH WOULD MELT BUTTER.”

In 1972, Robert Atkins, a cardiologist, published Dr. Atkins’ Diet Revolution, and he released a revised version in 2002. The various editions have sold more than 15 million copies. By keeping carb intake at an absolute minimum, dieters send the body into ketosis, a state in which it uses up fat as a fuel source. Apples are a no, but bacon is a go.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/3b/0d3b7085-0633-4ad6-a81c-05872a9466d7/gettyimages-101942366.jpg)

The 1980s saw the rise of the Beverly Hills Diet, based on the idea that certain foods should be combined and others shouldn’t. Fruit should only be eaten by itself, and pineapple in particular helps weight loss. Champagne is neutral and can be sipped with everything. In the era from the 1980s to the turn of the 21st century, the public whipsawed from thinking all fats were bad and carbs were good to fleeing carbs and embracing fat. In the 1990s, everyone was talking about the Mediterranean diet, based on healthy fats such as olive oil, whole grains, lean meats and fish, and lots of fresh vegetables. It is an ancient way of eating that nutritionists endorse to this day.

The remainder of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st saw the Zone diet, Sugar Busters diet, raw foods, the South Beach diet, Paleo diet, and Primal diet.

While Americans are not likely to return to bathing in thinning salts or having their bodies squeezed between electric rollers anytime soon, there are themes that come around again and again. The Atkins diet, the Banting diet, the Inuit diet of the 1920s, the keto diet and the 1960s’ Drinking Man’s Diet—which held that you could freely indulge in steak slathered in Béarnaise, Roquefort-topped salads and dry martinis as long as you didn’t accompany them with a baked potato—are variations on a theme.

And while on the surface, fad diets appear to be about “health” or a desire to achieve physical perfection—or at least get as close to it as we can—Adrienne Rose Bitar, author of Diet and the Disease of Civilization, thinks there’s more to it than that.

“Diets,” she writes, “stand in for the bigger debate about history, salvation, nature, money, power … and all the other ideas that make the world worth thinking about.”

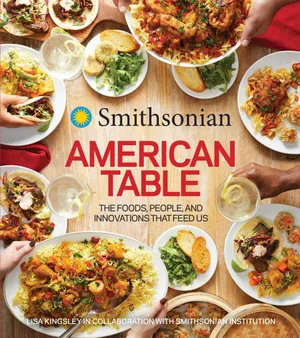

From SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN TABLE by Lisa Kingsley in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution. Copyright © 2023 by Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted by permission of Harvest, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.