Why Ernest Hemingway’s Younger Brother Established a Floating Republic in the Caribbean

On July 4, 1964, Leicester Hemingway founded New Atlantis, a raft-turned-micronation intended to support marine life in the region

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/83/de/83dedf3c-ddbd-4f42-884b-80362e8b50fe/leicester.jpg)

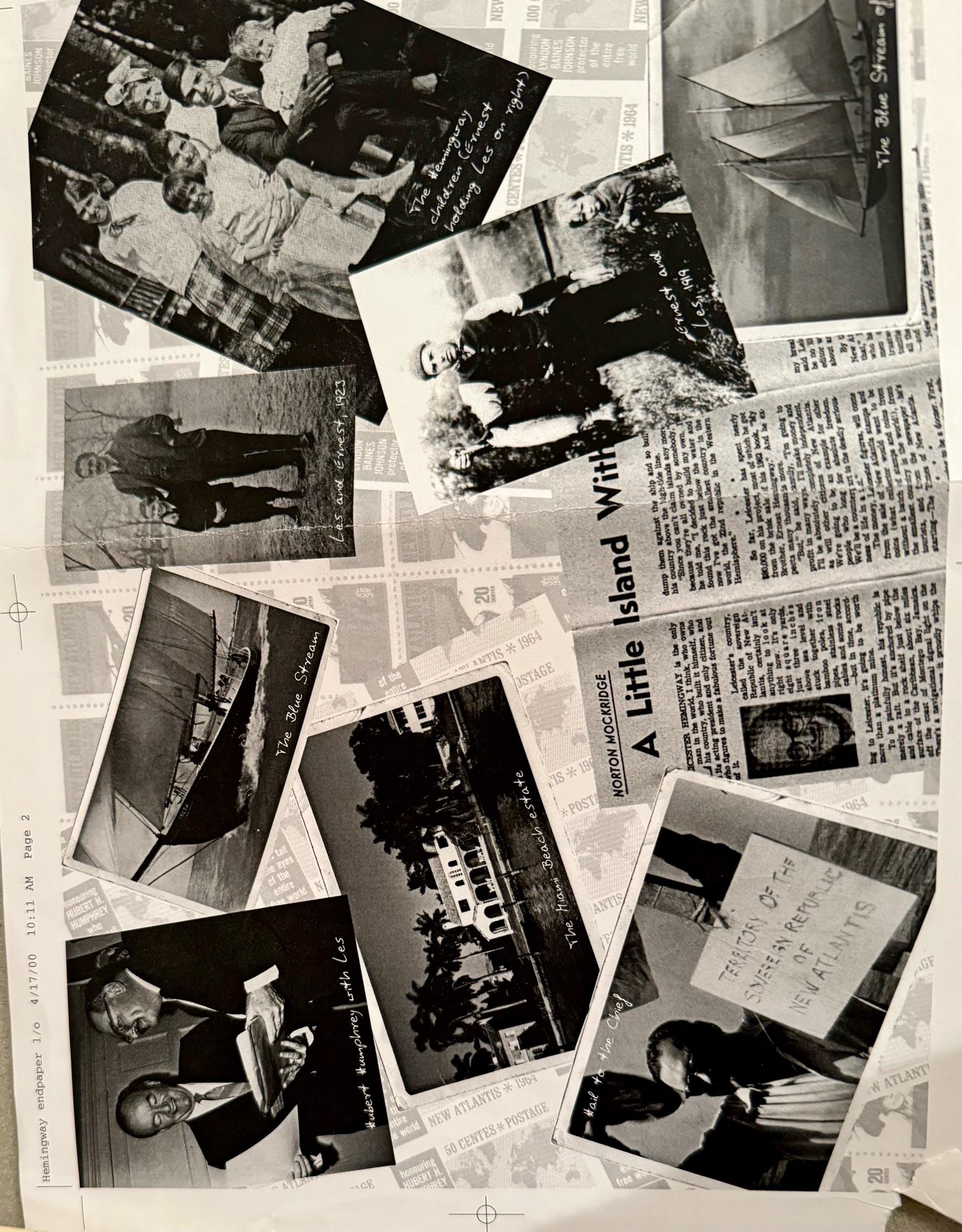

Founding a new country is no easy task. Ernest Hemingway’s younger brother, Leicester, learned this lesson the hard way 60 years ago, on July 4, 1964. While towns across the United States held Independence Day parades, and Alabama Governor George Wallace gave a speech denouncing the Voting Rights Act, Leicester (also known as “Les”) boarded a bamboo raft moored on a sandbank six miles off the coast of Jamaica. He raised a flag, an upside-down yellow triangle on a blue background, to announce the founding of New Atlantis. Later, to alleviate diplomatic tensions, he insisted that his 6-by-12-foot floating nation would be “a peaceful power and would pose no threat to Jamaica.”

The U.S.’s founders had groused about tyranny and taxation without representation. But Leicester had his own reasons for establishing a new country—in this case, a micronation, an independent entity that lacks recognition by the international community. As a sports fisherman, he wanted to help protect the Caribbean’s fisheries. In 1962, he’d chartered the International Marine Research Society, a group that previously existed only on paper. New Atlantan revenues could support marine research and even construction of an aquarium on Jamaica. Further, he regarded New Atlantis as a suitably audacious experiment in democracy, as well as a potentially profitable enterprise—and a chance to have fun.

Born on April 1, 1915, Leicester was a large, spirited man with a zany streak. His conversation, according to the Washington Post, was “soft and fast and funny.” He was 16 years younger than his famous brother, Ernest, the author of such classics as For Whom the Bell Tolls and A Farewell to Arms. The siblings’ mother, Grace Hall, had a brief career as an opera singer before her marriage to Clarence Hemingway, a doctor. Clarence died by suicide in 1928, after his health began to fail and his Florida real estate investments soured.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/9c/019c74f7-3314-4c3e-98c3-18d8152ab1d2/hemingway_family_circa_1917.jpg)

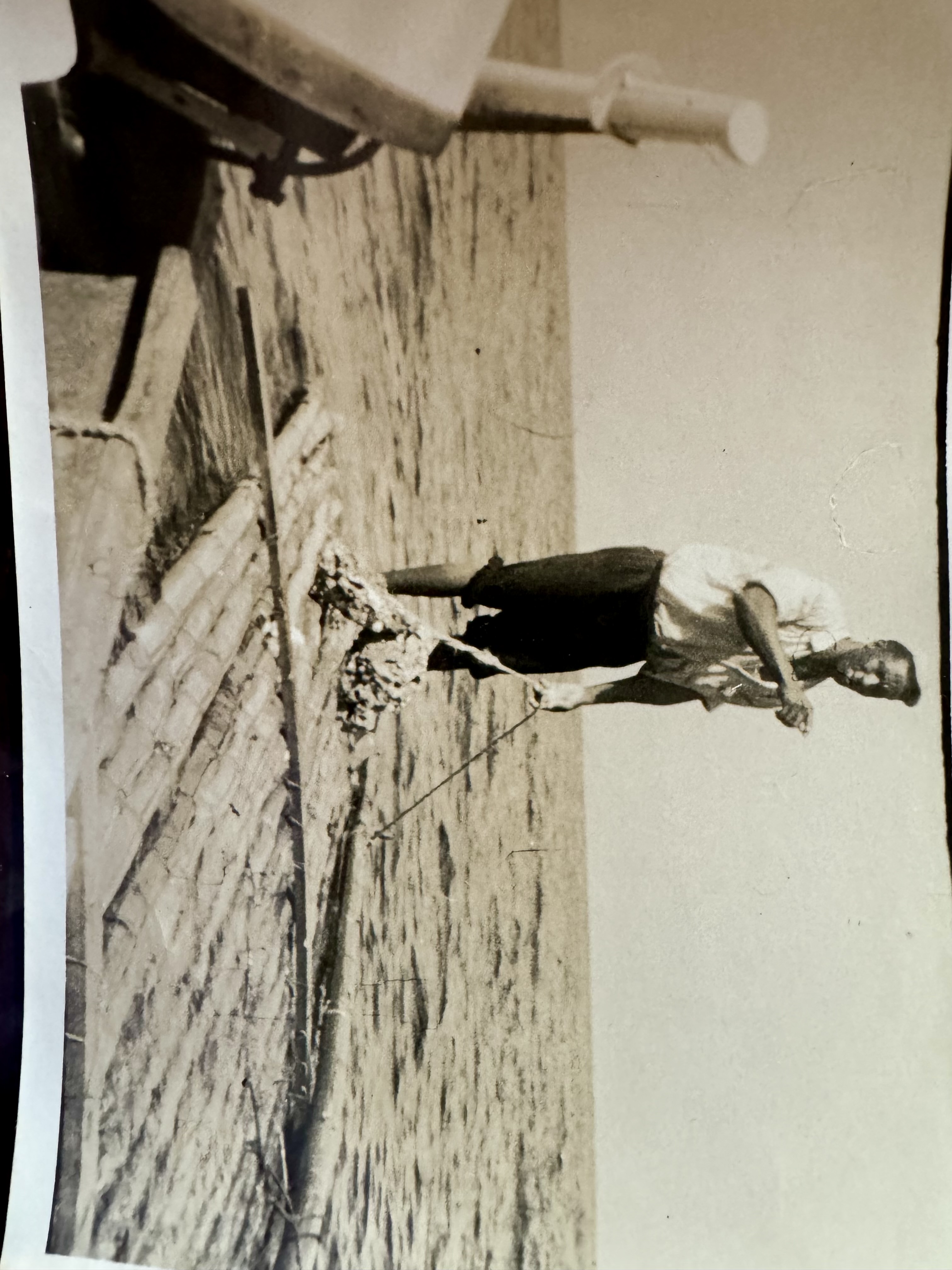

Like Ernest, the big brother he idolized, Leicester was an adventurer. As a teenager, he built a boat, which he and a friend sailed from Alabama, through storms, to join Ernest in Key West, Florida. When Leicester arrived, his brother said, “She looks awfully good for anything built by a Hemingway.”

During World War II, Leicester worked as a reporter and photographer with the Stars and Stripes newspaper, developing a daredevil reputation as he documented the conflict’s devastation. By the end of the decade, he had settled in Florida. Prior to the founding of New Atlantis, he and his second wife, Doris, lived on a 50-foot-long naval launch boat with their two young daughters, Anne and Hilary.

Hilary, who is now an artist, says the nation-building idea originated from her father’s childhood reading of National Geographic articles about underwater reefs that might eventually become islands. Further impetus arrived in the early 1950s, when Leicester aided a Jamaican government fishing survey, charting the waters off its coast.

The idea of creating an island first came to Leicester “as a wonderful book,” he told Philately and Numismatics in 1965. “The more I thought about it, the more I thought it would be more fun to carry it out than just to fictionalize it.” He wouldn’t just create an island, but rather a country, with himself as “first president and founder and fall guy,” as he wrote in a letter that same year.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9f/14/9f14e3d3-ad62-41cc-8cd9-4c8f75c6d96a/gettyimages-844536468.jpg)

Leicester gained the financial means to carry out his vision in 1962, when his book My Brother, Ernest Hemingway was serialized in Playboy magazine, one year after Ernest killed himself with a shotgun. Leicester had long been a professional writer, too. His output included The Sound of the Trumpet, a 1953 novel based on his World War II experiences, which earned mixed reviews from critics.

Leicester’s biography of his brother (whom he called “Papa,” while Ernest, in turn, called him “Baron”) was his most popular book; its proceeds gave him the resources and time needed to ferry old railroad wheels and axles, car engine blocks, cables, and industrial scrap from Jamaica out to a three-mile-long sand plateau. Dumping these loads overboard, Leicester created what Hilary calls not only an “environmental disaster zone” but also a foundation for mooring a raft.

Building New Atlantis helped Leicester step out from the shadow of his older brother. But he isn’t the only overlooked figure in this tale: The oft-neglected U.S. president Millard Fillmore also played a role in the micronation’s founding. A man who recognized the importance of guano (seabird droppings used as a natural fertilizer for crops), Fillmore paved the way for what became the Guano Islands Act of 1856. At the time, solidified deposits of guano measuring up to 200 feet deep coated undisturbed sea islands in the Pacific and the Caribbean. Fillmore believed this valuable resource, commonly nicknamed “white gold,” shouldn’t go to just anybody.

Historian Paul Finkelman, author of a 2011 biography of Fillmore, says the president “did not want to invade Cuba or Mexico, but [he] did have a notion of the United States expanding into the space between California and Asia.” Unfortunately for Fillmore’s reputation, though he pushed for the act, it was his successor, Franklin Pierce, who made it official. The law Pierce signed, Finkelman explains, “essentially says Americans could claim any uninhabited islands containing guano, and the United States government would protect their claims.”

A little over a century later, Leicester asserted that the Guano Islands Act made his raft a legitimate island deserving of U.S. protection. But Harry Hobbs, a legal scholar at the University of Technology Sydney who has written extensively about micronations and sovereignty efforts, contradicts this version of events. “Leicester said he found some guano on his raft,” Hobbs says. “This was after he had brought it there.” Finkelman, for his part, points out, “A raft is not an island.”

Technicalities aside, Leicester relied on the 1856 law to claim the northern half of the raft in the U.S.’s name. He dubbed the raft’s southern half the sovereign republic of New Atlantis, reasoning that the sandbank was more than three miles from Jamaica’s shore, placing it in international waters. (Subsequent laws have pushed the border between a coastline and international waters to at least 12 but in some cases as far as 200 nautical miles.)

Reluctant to lose his U.S. citizenship, Leicester declared himself an honorary citizen of New Atlantis, eligible to hold office but not to vote. To fill out the country’s ranks, Leicester recruited a small group of British nationals, who were allowed to hold dual citizenship. These new citizens included the Jamaican-based British socialite Lady Pamela Bird and the U.S. manager of the Cunard Line, Sidney Jones. No one actually lived on the raft. All one could do on board, Leicester admitted to the New York Times in 1965, was “walk around on it and salute the flag, all of which we do periodically.” He hoped to enlarge the makeshift island so he could “maybe entertain some people for lunch.”

Precedent for a micronation such as New Atlantis was meager. While numerous utopian colonies had cropped up and faded in the 19th century, the golden age of micronations only began after World War II. New Atlantis was among the first of these entities. As Hobbs says, “Prior to World War I, there were small principalities and duchies scattered around, as well as free cities, but after World War II particularly, it was the state or nothing. And this is where the idea of creating a micronation to exist within the state system had appeal.”

Hobbs separates these micronation attempts from postwar nationalist secession movements and anticolonial struggles. Micronations ran the gamut from utopian communes to libertarian breakaway republics to an Australian kingdom dedicated to gay and lesbian rights. Pirate radio stations and gambling operations were also common offshore but inevitably faced rapid government repression.

Regarding all such micronations, Hobbs says, “They had no legal basis. Your only way to legally be a nation is to be recognized by other nations, and that just wasn’t going to happen. No one was going to give someone like Leicester a seat on the United Nations.”

With the help of New York City public relations expert Edward K. Moss, Leicester made a determined if lighthearted effort at joining the world’s nation-states. The collection of New Atlantis memorabilia housed at the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center includes a copy of the micronation’s constitution, which borrows liberally from the seven main articles of the U.S. Constitution. Also featured, on stationary from the Mimosa Lodge in Kingston, Jamaica, are Leicester’s hastily scrawled notes for the first session of the Congress of New Atlantis, dated February 2, 1965, at 5:30 a.m.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5e/80/5e8042dd-3e57-4c21-9783-5daf7f2ec382/gettyimages-844536472.jpg)

Among Leicester’s early morning jottings: “Draft statutes frowning on murder, kidnapping, rape, robbery and double parking on main thoroughfares during business hours.” The notes also confirm Leicester’s decision to reject taxation and forbid gambling. He outlined lofty goals, such as “formal requests to other governments for provisional diplomatic recognition in near future, with Republic of N.A. using every resource to build permanent land above water on N.A. bank.”

Later that day, New Atlantis’ citizens adopted the constitution and elected Leicester president. Other newly appointed officials included Bird as vice president, Peter Patterson as keeper of the great seal and former U.S. President Harry Truman as presidential adviser.

To encourage the moral character of New Atlantans, Leicester introduced a monetary unit called the scruple. One scruple equaled 100 New Atlantan centes, or 50 U.S. cents. Instead of minting coins, the New Atlantans turned to materials found at sea. These included a shark’s tooth (100 centes), a fishhook (50 centes) and bit of a broken barrel stave (10 centes). “What the hell,” Leicester wrote in a letter. “We made [the money,] and we stand by it. It’s legal.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/82/2a/822ab357-a929-4dad-8d52-e027d185a0be/stamps.jpg)

New Atlantan postage stamps, as in many a small nation, served as a prime source of revenue. They were a polished production. One of the micronation’s first stamps, priced at 60 centes, featured Winston Churchill, described as “world statesman of XX century.” New Atlantis also printed a 50-cente stamp honoring U.S. Vice President Hubert Humphrey and a 100-cente stamp praising President Lyndon B. Johnson as “protector of the entire free world.” Other stamps paid tribute to the Dominican Republic and the U.S. Army’s Fourth Infantry Division, whose World War II campaigns both Ernest and Leicester had chronicled as journalists.

The U.S. government offered New Atlantis some sideways recognition. When Leicester requested permission from the Treasury Department to print stamps and mint coins, Assistant General Counsel George Reeves responded, “It is my opinion that this department would have no objection to the plans you have proposed as you describe them.”

“I have no intention of discouraging legitimate operations by the republic,” Reeves added, but he cautioned Leicester against making stamps or coins that could be mistaken for those of the U.S. or another legitimate country. After Leicester sent sample stamps to the White House, a Johnson staffer returned a letter of thanks addressed to “Leicester Hemingway, Acting President, Republic of New Atlantis.”

Between New Atlantis’ founding and the formal adoption of its government, the raft, presumably rebuilt, had more than tripled in area, to 8 by 30 feet. But Leicester had even greater expansion plans. The raft floated above a sand plateau, 50 feet below the surface, in water otherwise about 1,000 feet deep. In September 1964, Leicester told the New York Herald Tribune that he planned to sink “several surplus Navy concrete hulled vessels” on the bank. This would put the tops of the ships above the ocean surface. He would then “cart over several Jamaican hills he had bought to fill in around the sunken hulls.” The New York Times reported that Leicester’s goal was to make the island half a mile long, big enough to “accommodate a lighthouse, short-wave radio station, customs house and post office.”

The New Atlantans parlayed with cruise ship lines to make mail stops at the raft. They also sought to aid local fishing. Leicester hoped to convince the U.S. and Jamaican governments to keep passing boats from inadvertently cutting the lines attached to local fishers’ large sunken fish traps. New Atlantis would also profit from the area’s reputation for fishing. In addition to stamp sales (with proceeds benefiting the marine research society), Leicester planned to sell a Sea Turtle Cookery Book bound in sharkskin and a small newspaper titled the Times of New Atlantis.

Problems plagued the effort from the beginning. Leicester reported that local fishers had swiped at least two of New Atlantis’ flags, while storms wiped out several iterations of the raft. The Jamaican government regarded New Atlantis with benevolence, with one spokesman dubbing Leicester a “decent, well-meaning soul.” But no nations officially recognized the country, and even Leicester acknowledged that the Universal Postal Union would likely not admit New Atlantis and make its stamps functional. When yet another tropical storm destroyed the latest raft in 1966, news from New Atlantis ceased.

As Hilary recalls, “When my dad got his last royalty check for the biography, my mom said, ‘We’re buying a house, so my kids have an address.’” The family purchased a home on an island in Miami’s Biscayne Bay. Though Leicester theorized to a friend that a sandbar sheltered by a reef in international waters would be an ideal spot for yet another island nation, he begrudgingly moved on to new projects. He churned out articles about the sporting life; hawked a tourist hotel in the Virgin Islands; performed other public relations work; and developed several book manuscripts, including one about the moon’s positive effect on human sexual activity. Leicester also had a paid column in the Miami Herald covering the Basque sport of jai alai.

But his happy place was Bimini, the island in the Bahamas where Ernest had lived in the 1930s and taken on all types of challengers in boxing matches. In the mid-1970s, from his base in Miami, Leicester flew out to Bimini on a propeller plane once a week. He also published the Bimini Out Island News, a newsletter with “all the fishing news that’s fit to print.”

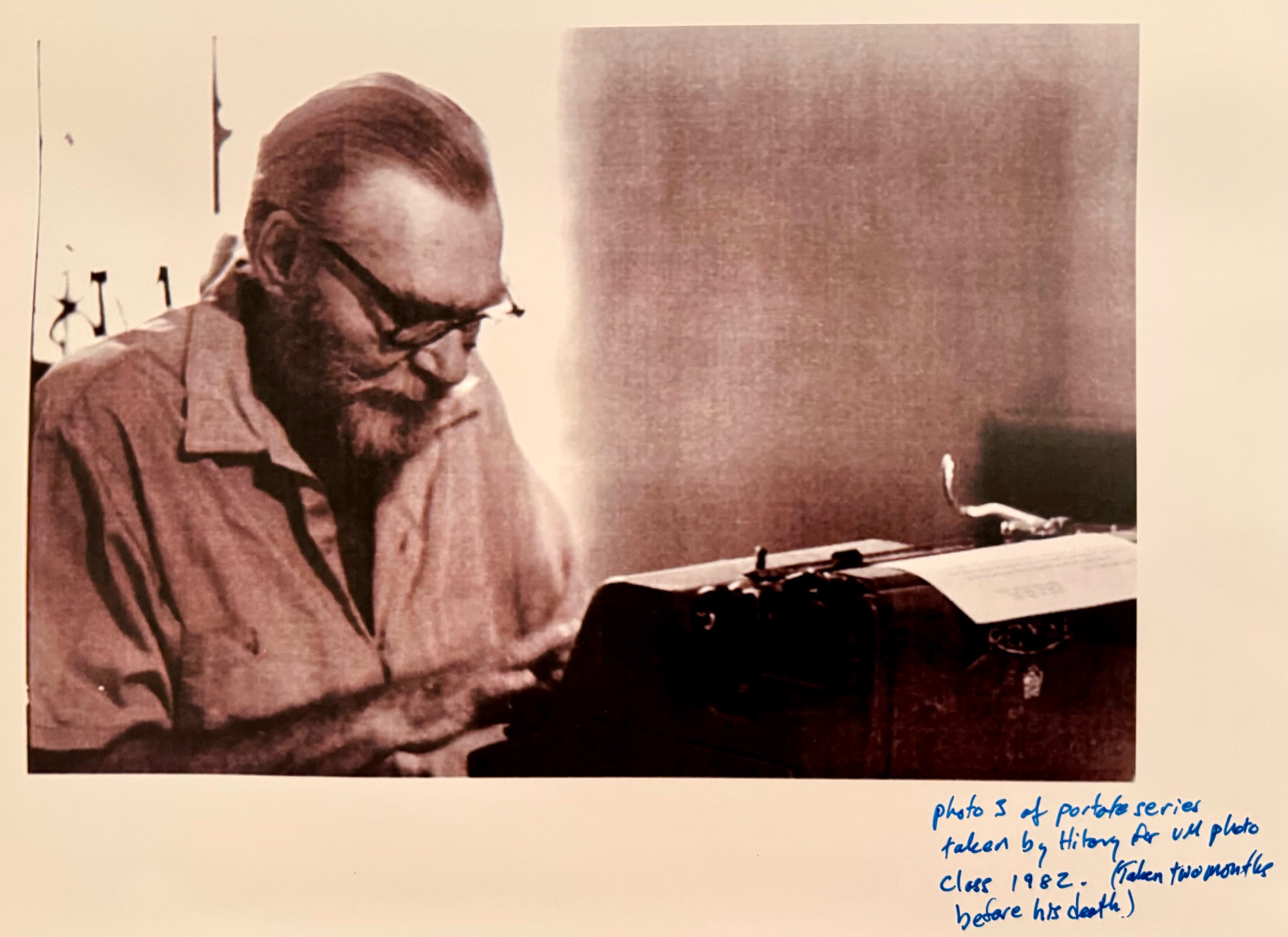

Leicester became intrigued with the underwater search for evidence of the “real” Atlantis, even theorizing that a secluded spring in Bimini may have been the fabled Fountain of Youth. But Bimini’s healing springs could not restore his own health. In 1982, after several surgical procedures to treat Type 2 diabetes, doctors told Leicester his legs would need to be amputated. On September 13, 1982, like his brother and father before him, Leicester shot himself with a handgun, a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson borrowed from a neighbor. His father had killed himself with the same type of weapon 54 years earlier.

Though it vanished beneath the sea, Leicester’s dream of a country that offered “a brand new chance for all the little guys in the world,” as he told the Washington Post in 1965, sent out ripples. Media coverage of New Atlantis inspired Japanese writer Hisashi Inoue, who published his novel Kirikirijin a year before Leicester’s suicide. In this political satire, a novelist travels to the rural village of Kirikiri, which has seceded from Japan and declared itself a sovereign nation. The book was a sensation, and in quick order, some 200 small villages in Japan declared themselves micronations, primarily to encourage tourism.

As Hilary says, “The whole thing was remarkable. We may imagine building an island, but my dad took it one step further and wanted to build a nation. There’s some appeal there. With all that’s going on these days, wouldn’t it be nice to have a country to escape to?” She hesitates, then adds, “But with climate change, I’m not going to hop on a raft when there are 200-mile-per-hour hurricanes blowing.”

On the 60th anniversary of New Atlantis’ founding, Leicester’s actions are open to interpretation. Was the micronation a quixotic experiment in democracy or an elaborate improv comedy sketch? Either way, says Hilary of the republic’s demise, “It’s kind of poetic. New Atlantis, like the original Atlantis, sank into the waves.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/fred3.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/fred3.png)