What the American Revolution Taught the United States’ First Presidents

A new book by historian William E. Leuchtenburg examines how the first six commanders in chief embodied the revolutionary spirit and set precedents that shaped their successors’ tenures

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b5/ee/b5ee1843-0e08-48e7-94cf-53f623333c0b/patriot-pres2.jpg)

As a young boy in the summer of 1932, William E. Leuchtenburg stayed up late, glued to the live radio broadcast that culminated in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s nomination for president. The then-New York governor’s appearance in Chicago lit up the Democratic National Convention floor—and it marked a big milestone: Roosevelt was the first candidate to accept the nomination in person at the convention.

“I have started out on the tasks that lie ahead,” the nominee said, adding, “Let it also be symbolic that in so doing, I broke traditions.” Roosevelt pledged to offer “a New Deal for the American people,” boosting the progressive policy that would define his presidency.

Leuchtenburg, who is now 101, traces his interest in presidential history to this moment. A veteran scholar of American politics, his latest research venture is a multivolume history of the government’s top job.

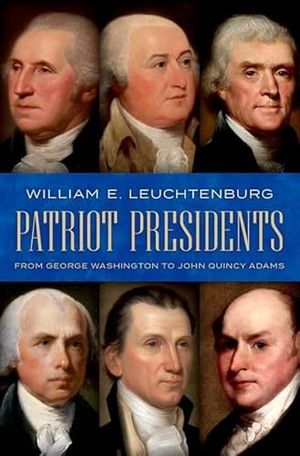

Patriot Presidents: From George Washington to John Quincy Adams

The esteemed American historian William E. Leuchtenburg invites readers to revisit the years after the birth of the republic, when Americans could take pride in leaders of ideals, high competence and integrity who headed their government.

First up in the series is Patriot Presidents: From George Washington to John Quincy Adams, a panorama of the six founders who launched the office of commander in chief. These men dealt with contentious elections, the question of slavery, political party tumult, domestic rebellion and foreign crises that carved out executive power. As American liberty grew from theory to practice, they fought to bring the “Spirit of ’76”—a patriotic sentiment that indicated “their determination to create new institutions appropriate for a republic,” says Leuchtenburg—to the daily work of running a new nation.

“The founders seem remote today,” writes the historian in Patriot Presidents, “… but their presidencies provide an instructive measuring rod for 21st-century incumbents.”

Smithsonian chatted with Leuchtenburg via email to learn more about the origin story of the American presidency. Read on for a condensed and edited version of the conversation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e3/8a/e38af298-595a-4122-9a06-fc72ad2261f0/bill-leuchtenburg.jpg)

How can we define the “Spirit of ’76”? How did these six presidents evolve from revolutionaries to leaders of a free people?

The “Spirit of ’76” projects its origin in the intention of colonists in 1776 to separate themselves from the British Empire and to end their inferior status as colonials. In the course of fighting the Revolutionary War, rebels who had been thinking of themselves as citizens of particular states came to regard themselves as Americans.

The first six presidents both elucidated that vision and gave substance to the provision for new republican structures outlined in the [United States] Constitution. In particular, the national charter provided for a powerful executive branch flanked by a bicameral legislature and a multilayered judiciary.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1c/0a/1c0a9f49-19de-4cc5-ad26-1537886da3a4/sprit_of_762.jpeg)

George Washington’s actions as president were largely invention by way of the U.S. Constitution. What moments shaped his interpretation of the office?

When historians are called upon to rank American presidents, they regularly accord the category “great” to only three: Washington, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt. It is not difficult to understand why that high rating is accorded to Lincoln and Roosevelt, because one readily recognizes that they presided in times of great turmoil, when the survival of the republic was in danger.

Many Americans, while understanding that Washington was essential to the success of the revolution in his role as commanding general, would be hard put to explain why he is so highly ranked as president. Washington, though, merits that stature because he set the example of a man who exercised the powers accorded to him but who was also ready to relinquish power.

Washington is such a well-known figure. What surprised you about his outlook?

Europeans, fully expecting Washington to take advantage of his election to become a dictatorial ruler, a “man on horseback,” found his respect for a republican ethos both surprising and admirable. In 1956, when I lectured to a gathering of young European intellectuals at the Salzburg Global Seminar in Austria, a young German woman said to me, “You Americans don’t realize how fortunate you are in having as a model not [German Chancellor Otto von] Bismarck but George Washington.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/09/40/09403f36-46b3-43ea-978a-4c3dd7e52024/1280px-life_of_george_washington_deathbed.jpg)

What especially impressed me, in writing about Washington, was his sensitive awareness that even when he took what textbooks regard as routine actions, such as appointing officials concerned with domestic policy, he was setting precedents. Understandably, Washington was seen by contemporaries as the American Pericles [a Greek politician who presided over the Golden Age of Athens].

How did John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams envision the “Spirit of ’76” or feel limited by it, a generation apart?

John Adams has never been adequately appreciated for his service to republican ideals and his assertion of leadership. It has been pointed out that, though characters such as Washington and [Thomas] Jefferson have monuments in Washington, there is none for Adams. He is rightly honored by historians for his role in ending an undeclared war with France that was perilous to the survival of the republic, and it needs to be acknowledged, too, that he bequeathed a legacy of strong presidential leadership to his son.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/10/33/1033277a-c69d-400a-90f4-e21b1300b583/jqa_photo_crop_cropped.jpg)

That was significant because, though Adams was on the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence, his son was still a boy during the revolution. John Quincy Adams carried the “Spirit of ’76” still further by providing a model for later presidents, including the Roosevelts, of a chief executive who could create an office that directly intervened in the economy on behalf of social justice. [The sixth president pushed for internal improvements, like better roads, canals and bridges, as part of a plan known as the “American System.” He was also an antislavery advocate who supported the idea of a self-sufficient U.S. economy that made the most of regional specialties.]

One of the great strengths of Patriot Presidents is that you “Remember the Ladies” and sketch the political roles of Abigail Adams, Dolley Madison, Louisa Catherine Adams, Elizabeth Monroe, Margaret Bayard Smith and other founding mothers. How were these women involved in presidential contests?

The women who are major figures in the first generation of the American presidency not only made important contributions to its expansion but also served as commentators who helped viewers understand the significance of what was happening. Scholars enrich accounts of the first years of the American presidency when they pay serious attention to the contributions that these women made to a new republican polity.

Since women were denied suffrage and lived in a repressive culture that stipulated intolerance for a public role for women, they did not have in these years, and could not be expected to have, the kind of public role performed so brilliantly by Eleanor Roosevelt, [Secretary of Labor] Frances Perkins, Lady Bird Johnson or Jill Biden. Nonetheless, they managed to make their presence felt in public affairs. Abigail Adams was a trusted adviser for John Adams, as is apparent in their many years of frequent correspondence. Both Dolley Madison and Elizabeth Monroe set the tone for the way that their respective husbands’ administrations were perceived.

Scholars would do well to expand their measures of significant influence by women on public affairs beyond electioneering. In my 1986 presidential address to the Organization of American Historians, I wrote, “Groups that have not been part of the elite have often been affected by the state, and have affected it, in ways that have only recently begun to be appreciated. That perception informs much of the recent history of women, ostensibly outside the orbit of the state during the long period when they were denied the suffrage.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/0e/d10ee22b-8521-4fe1-b499-b83389bd2608/dolley_madison_daguerreotype_06.jpg)

Each president featured in your book offers a case study in executive power, as they struggled to advance national growth and heed party interests. How did Jefferson and James Madison, both party leaders turned presidents, compare on this point?

The framers disliked the very notion of “party,” for they believed that what they called “factions” had been injurious to earlier attempts to create viable republics. Madison was the most thoughtful of the framers, as he demonstrated in his essays in The Federalist [Papers], but Jefferson was more significant as a party leader in the presidency because he was the first chief executive to come to office after a change of party control. [Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, defeated the incumbent president, Federalist John Adams, in the election of 1800.] He also made full use of party institutions in wielding power, while Madison, though an important party leader when in Congress, had much less success as chief executive.

James Monroe contended with the realities of a republic expanding into an empire. How did this political backdrop alter the office of president?

Monroe fully understood that presidents are granted far greater amplitude to exercise power in foreign affairs than in the domestic realm. The framers limited presidential authority in foreign policy by stipulating that Congress was vested with the power to declare war and that the negotiation and ratification of treaties be shared with the Senate, but Monroe’s initiatives served as examples for his successors to launch forays abroad, even to decide between war and peace.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/fc/99fc6425-0031-4f6b-8a20-fe83fc1431af/chester_harding_-_james_monroe_-_npg200544_-_national_portrait_gallery.jpg)

Though it took a while for the Monroe Doctrine to become revered, Monroe’s bold assertions continued to give wide scope to a chief executive’s claims to power centuries after they were first enunciated. By taking advantage of options such as joint resolutions, recent presidents have overcome the restrictions imposed by subjecting a chief executive to Senate approval for his actions overseas.

What was it like to shift the historical landscape away from the 20th century?

My venture into the origins of the presidency in the late 18th century and early 19th century was largely a daunting departure for me, but not wholly so. When I was a graduate student at Columbia University, the most highly regarded textbook was The Growth of the American Republic by Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager. When these celebrated senior scholars asked me to join them in revising and updating the tome [in 1969], “Morison and Commager” became “Morison, Commager and Leuchtenburg.” [The project] required me to revamp accounts of all of American history, including the period covered in Patriot Presidents.

Yet it is true that almost all of my previous publications deal with the modern era, especially the age of Roosevelt. When I was a boy of 9 in the summer of 1932, I persuaded my parents to let me stay up late to listen on the radio to proceedings at the Democratic convention that wound up nominating him. In later years, when I wrote about Roosevelt’s career, I had the comfort of familiarity with the period I had lived through.

In writing of the early republic, I had to step more warily. When Americans assess the performance of presidents today, they will find it pertinent to familiarize themselves with the design of the framers and with the standards set by the first six presidents.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)