On a bright day early in 1885, Zelia Nuttall was strolling around the ancient ruins of Teotihuacán, the enormous ceremonial site north of Mexico City. Not yet 30, Zelia had a deep interest in the history of Mexico, and now, with her marriage in ruins and her future uncertain, she was on a trip with her mother, Magdalena; her brother George; and her 3-year-old daughter, Nadine, to distract her from her worries.

The site, which covered eight square miles, had once been home to the predecessors of the Aztecs. It included about 2,000 dwellings along with temples, plazas and pyramids where they charted the stars and made offerings to the sun and moon. As Zelia admired the impressive buildings, some shrouded in dirt and vegetation, she reached down and collected a few pieces of pottery from the dusty soil. They were plentiful and easy to find with a few brushes of her hand.

The moment she picked up those artifacts would prove to be pivotal in the life and long career of this trailblazing anthropologist. Over the next 50 years, Zelia’s careful study of artifacts would challenge the way people thought of Mesoamerican history. She was the first to decode the Aztec calendar and identify the purposes of ancient adornments and weapons. She untangled the organization of commercial networks and transcribed ancient songs. She found clues about the ancient Americas all over the world: Once, deep in the stacks of the British Museum, she found an Indigenous pictorial history that predated the Spanish conquest; skilled at interpreting Aztec drawings and symbols, and having taught herself Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and their predecessors, she was the first to transcribe and translate this and other ancient manuscripts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/68/dc/68dcf9a7-c7bd-446e-816e-13264ea4525c/nov2023_h06_zelianuttall.jpg)

She also served as a bridge between the United States and Mexico, living in both countries and working with leading national institutions in each. At a time when many scholars spun elaborate and unfounded theories based on 19th-century views of race, Zelia looked at the evidence and made concrete connections based on scientific observations. By the time she died, in 1933, she had published three books and more than 75 articles.

Yet during her lifetime, she was sometimes called an antiquarian, a folklorist or a “lady scientist.” When she died, scholarly journals and some newspapers ran notices and obituaries. After that, she largely passed from the public’s eye.

Today, anthropologists often have specialized expertise. But in the 19th century, anthropology was not yet a discipline with its own paradigms, methods and boundaries. Most of its practitioners were self-taught or served as apprentices to a handful of recognized experts. Many such “amateurs” made important contributions to the field. And many of them were women.

She was born in 1857 to a wealthy family in San Francisco, then a fast-growing city of about 50,000 people. Near the shore, ships mired in mud—many abandoned by crews eager to make their fortunes in the gold fields—served as hostels to a restless, sometimes violent and mostly male population. Other adventurers found uncertain homes in hastily built hotels and rooming houses. But the city was also an exciting international settlement. Ships arrived daily from across the Pacific, Panama and the east via Cape Horn.

Her well-appointed household stood apart from the city’s wilder quarters, but the people who lived there reflected San Francisco’s international character. Her mother, Magdalena Parrott Nuttall, herself the daughter of an American businessman and a Mexican woman, spoke Spanish, and her grandfather, who lived nearby, employed a French lady’s maid; a nursemaid from New York; a chambermaid, laundress, housekeeper, coachman and groom from Ireland; a steward from Switzerland; a cook and additional servants from France; and nine day laborers from China.

When Zelia was 8, her family left San Francisco for Europe. Along with her older brother, Juanito, and her younger siblings Carmelita and George, Zelia and her parents set off for Ireland, her father’s native land. Over the course of 11 years, the Nuttalls made their way to London, Paris, the South of France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. Throughout that time, Zelia was educated largely by governesses and tutors, with some formal schooling in Dresden and London. But her time overseas shaped her interest in ancient history and expanded her language skills, as she added French, German and Italian to her fluent Spanish. All of this expansion thrilled her mind, but it also made her feel increasingly out of step with the expectations for young women of her age. “My ideas and opinions form themselves I don’t know how, and I sometimes am astonished at the determined ideas I have!” she wrote in a November 1875 letter.

She took refuge in singing and tried to be pleased with the few social events she attended. Photos from the time show Zelia as an attractive young woman with large, dark eyes, arched eyebrows and stylishly arranged hair. Nevertheless, she was unhappy. “I was infinitely disgusted with some of the idiotic specimens of mankind I danced with,” she wrote in an 1876 letter after a party.

The Nuttalls returned to San Francisco in 1876, when she was nearly 20. Two years later, she met a young French anthropologist, Alphonse Pinart, already celebrated in his mid-20s as an explorer and linguist. He had been to Alaska, Arizona, Canada, Maine, Russia and the South Sea Islands. Pinart may have led the family to understand that he was wealthy. In fact, he was almost penniless, having already spent his significant inheritance.

They were married at the Nuttall home on May 10, 1880. During the next year and a half, the couple traveled to Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Mexico. Pinart introduced Zelia to a burgeoning academic literature in ethnology and archaeology, and she began to understand the theories of linguistics. She found 16th-century Spanish hardly a challenge as she consulted annotated codices—pictorial documents that traced pre-Columbian genealogies and conquests in Mesoamerica. While Pinart dashed from project to project and roamed widely among countries, tribes and languages, Zelia began to demonstrate an intellectual style that was more focused and precise.

Despite the excitement of discovery, something began to go wrong in the marriage. Hints of Zelia’s distress can be found in her effusive letters home. There was, for example, the shipboard admission that her husband was less attentive than she had anticipated. She noted that he was “so quiet and undemonstrative” that it was hard to imagine they were newly married. Some fellow passengers thought they were brother and sister—an odd assumption to make, even in Victorian times, about newlyweds.

By contrast, Zelia is nowhere to be found in Pinart’s surviving correspondence. On April 6, 1881, she gave birth to a daughter, Roberta, who lived only 11 days. To add to this melancholy time, her beloved father died in May, leaving her doubly devastated. A letter Pinart wrote to a friend just a few months later from Cuba appeared on stationery with a black border, signifying mourning, but he made no reference to his wife, her father or their child.

Zelia found solace in learning about her heritage when she and Pinart traveled to Mexico in 1881. She was eager to see her mother’s homeland and to hone her understanding of its pre-Columbian cultures. While Pinart carried out his own research, she began to learn Nahuatl, and she toured villages where dialects of the language were still spoken and ruins where the marks of the past could still be found.

The couple returned to San Francisco on December 6, 1881. By then, Zelia was pregnant again. In late January, Pinart set out to spend several months in Guatemala, Nicaragua and Panama, while Zelia awaited the birth of her second child, Nadine, at her mother’s house.

What finally drove Zelia to sue for divorce, on the grounds of cruelty and neglect, remains elusive. She may have felt that Pinart had married her for access to her family’s fortune. Many years later, she angrily informed Nadine that Pinart had spent the $9,000 she had inherited from her father as well as her marriage settlement. When the money was gone, and when her family was firm that he shouldn’t expect any more, he abandoned his wife and child. Once Zelia demanded a separation, he did not contest it, though obtaining the divorce was a long process that started soon after the couple’s return from their travels and didn’t conclude until 1888.

In later life, Nadine Nuttall Pinart would reflect on how much it had cost her to grow up without a father. “From the time before I can remember, he was taboo to me,” she wrote in a 1961 letter to Ross Parmenter, a New York Times editor who wrote numerous books about Mexico and developed a fascination with Zelia Nuttall. “I was frightened by the violent scoldings I got for mentioning his name. Later, I compromised with myself and when asked about him quietly said, ‘I never knew him!’ I realized that people thought he was dead and were sorry for me and said no more. In those days it was a disgrace to have a divorced mother.”

If the period between 1881 and 1888, when Zelia finalized her divorce, was fraught with tension and heartache, this was also when she set about redefining herself as a woman with a vocation. She spent five months in Mexico with her mother, her daughter and her brother between December 1884 and April 1885, visiting Cuernavaca, Mexico City and Toluca, and exploring archaeological ruins. It was during this time that Zelia made her fateful winter visit to Teotihuacan and acquired her first artifacts.

The pieces of pottery she picked up that day were small terra-cotta heads. They were abundant in the area among the pyramids. At the time, the site was still being used as farmland, and the artifacts came to the surface during ploughing. The heads themselves were an inch or two long, with flat backs and a neck attached. Scholars before Zelia—Americans, Europeans and Mexicans—had mused creatively about such relics, describing differences in their facial features and the variety of headdresses they had sported. Drawing on 19th-century fascination with the topic of race, the French archaeologist Désiré Charnay became convinced that he could see in them African, Chinese and Greek facial features. Charnay mused: Had their creators migrated from Africa, Asia or Europe? And if racial identity was a marker of human development, as many believed at the time, what might this curious mixture of features reveal about civilizations in the Americas?

This kind of thinking was typical. Mistaken ideas about Darwinism led many Western scholars to believe that civilizations evolved along a linear, hierarchical path, from primitive villages to ancient kingdoms to modern industrial and urban societies. Not surprisingly, they used this to legitimize beliefs about the superiority of the white race.

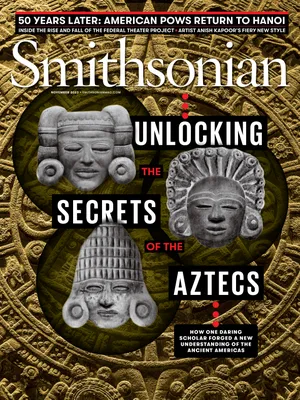

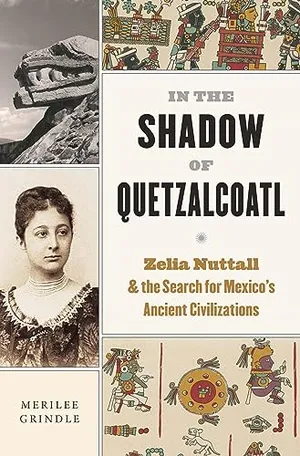

In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations

The gripping story of a pioneering anthropologist whose exploration of Aztec cosmology, rediscovery of ancient texts, and passion for collecting helped shape our understanding of pre-Columbian Mexico.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6d/6c/6d6cc430-f2c8-42f4-80c4-89a24970099c/heads.jpg)

Zelia generally accepted her era’s assumptions about race and class, and she was comfortable with her elite status and its privileges. Yet in her research, she did not categorize civilizations as primitive, savage or barbaric, as other scholars did, nor did she indulge in racial theories of cultural development. Instead, she sought to sweep aside this kind of speculation and replace it with observation and reason.

The more Zelia examined her terra-cotta heads, the more she realized she needed guidance from someone who had more experience in the study of antiquity than she had. At the time, there were no departments of anthropology in colleges or universities, no degrees to be earned, no clear routes to building a career. To pursue her burgeoning interest in the ancient civilizations of Mexico, and to decipher the meaning of an assortment of terra-cotta heads, she contacted Frederic Ward Putnam, the curator of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology and a leading expert on Mesoamerica. He agreed to meet her in the fall of 1885. The meeting was all she hoped for: Putnam warmed to her work and encouraged her to follow her intuitive grasp of how to observe and interpret evidence.

Putnam’s regard for women’s intellectual capacities was clear. He was one of a small number of Harvard researchers who gave lectures at “the Annex,” an institution established for women who had passed the college’s admissions test but were not allowed to attend classes or earn a degree. (The Harvard Annex eventually became Radcliffe College.) He hired a resourceful administrative staff of women and encouraged them to play a role in managing the museum. He also had a “correspondence school,” which he conducted through a widespread exchange of letters. As he once wrote, “Several of my best students are women, who have become widely known by their thorough and important works and publications; and this I consider as high an honor as could be accorded to me.”

Within months of their first encounter, in late 1885, Putnam asked Zelia to become a special assistant in Mexican archaeology for the Peabody. Less than a year later, in the annual report of the Peabody Museum, he wrote about her appointment in glowing terms: “Familiar with the Nahuatl language … and with an exceptional talent for linguistics and archaeology, as well as being thoroughly informed in all the early native and Spanish writings relating to Mexico and its people, Mrs. Nuttall enters the study with a preparation as remarkable as it is exceptional.”

With guidance from Putnam, Zelia wrote an investigation of the terra-cotta heads, her first published scientific report, which appeared in the spring 1886 issue of the American Journal of Archaeology. “At the first glance,” she wrote, “the multitude and variety of these heads are confusing; but after prolonged observation, they seem to naturally distribute themselves into three large and well-defined Classes.”

Each class, she theorized, had been created at a different time and represented a different stage in the culture. The first class contained “primary and crude attempts at the representation of a human face.” The second class included the first efforts at artistry. Her inspection revealed “holes, notches and lines,” suggesting ways in which tiny headdresses, feathers or beads could have been attached to the heads, and noted traces of several colors of paint and different kinds of clay.

The third class was the most important, Zelia argued, because of the quality of the molding and carving. This class had “modifications of feature sufficient to give every specimen an individuality of its own,” she wrote. “The faces are invariably in repose, in some the eyes are closed … faces young and smooth, others very elongated, some with sunken cheeks, others with wrinkles.”

By comparing these terra-cotta heads with ancient pictographs and writings, she showed that some of the heads represented children while others depicted young men, warriors or elders. Others showed the distinct hairstyles described in the writings of Bernardino de Sahagún, a 16th-century Franciscan friar who spent 50 years studying the Aztec culture, language and history. “The noblewomen used to wear their hair hanging to the waist, or to the shoulders only. Others wore it long over the temples and ears only,” Sahagún had written. “Others entwined their hair with black cotton-thread and wore these twists about the head, forming two little horns above the forehead. Others have longer hair and cut its ends equally, as an embellishment, so that, when it is twisted and tied up, it looked as though it were all of the same length; and other women have their whole heads shorn or clipped.”

These concrete observations allowed Zelia to challenge popular ideas about the supposed African, Asian, European or Egyptian origins of the “races” in the Americas. For example, by studying the ornamentation the heads displayed, she was able to identify the person or god each artifact represented and interpret its ritual or symbolic purpose. One clearly corresponded with Tlaloc, the pan-Mesoamerican god of rain, who had been shown in the pictographs with a curved band above the mouth and circles around the eyes. Another head, molded with a turban-like cap, corresponded with the goddess Centeotl; Zelia speculated that the clay turbans once had real feathers attached. She also noted the significance of various poses. “In the picture-writings, closed eyes invariably convey the idea of death,” she wrote.

The article revealed how Zelia intended to be seen as a scholar. First, she made it clear that she had read what others had written. Then she revealed that she would go beyond existing speculation to answer questions that had puzzled others; hers was to be original and important work.

In 1892, Zelia presented a paper in Spain about the Aztec calendar stone. Buried during the destruction of the Aztec Empire, the calendar stone had been unearthed in December 1790, when repairs were being made to the Zócalo, Mexico City’s central plaza. The sculpted stone, some 12 feet in diameter and weighing 25 tons, became a popular attraction exhibited in the Mexico City Cathedral, steps from where it had been found. Antonio de León y Gama, a Mexican astronomer, mathematician and archaeologist, had written about its discovery and praised the intelligence of the Aztecs who had created it. Alexander von Humboldt, who saw the stone when he visited Mexico in 1803-1804, included a drawing in his Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, published in 1810, and encouraged Mexican intellectuals to study the meaning of its concentric circles and numerous glyphs. Many others took on its puzzles in the years that followed.

At the time of Zelia’s presentation, the Mexican upper classes were carefully crafting a new national image—a story that would allow Mexico to take its place among the modern nations of the world. The Aztecs, Maya, Olmecs, Toltecs, Zapotecs and other cultures had left their imprints throughout the country in magnificent temples, enigmatic statues, gold jewelry, jade figurines and painted murals. This history was reclaimed as a national heritage every bit as glorious as those of Greece and Rome. A statue of Cuauhtémoc, the Aztec king who resisted Cortés, took its place on Mexico City’s elegant Paseo de la Reforma in 1887. The calendar stone had been installed in a place of honor in the National Museum in 1885. But little was known about the actual customs and beliefs of those ancient people.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/69/7e/697ec2d9-3e8a-43ee-bd48-a6ee0eabe2fb/nov2023_h11_zelianuttall.jpg)

With her extraordinary knowledge of surviving codices, Zelia offered a novel “reading” of the giant calendar stone that had stumped others and provided new insights into the annual and seasonal cycles of daily life in ancient Mexico, illuminating the cosmology, agriculture and trade patterns of the Aztecs. She presented another version of the paper at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

Zelia returned to Mexico City in February 1902, and after a personal audience with Mexican President José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz, arranged by the U.S. ambassador, she embarked on a spree of travel to archaeological sites she had long wanted to visit. In May, she and 20-year-old Nadine joined friends at the Oaxacan ruins at Mitla, a religious center, where the “place of the dead” harbored both Mixtec and Zapotec art and architecture. On this dry, high plain ringed by mountains, Zelia strolled across vast stone patios, inspected the elaborate geometric friezes that lined and decorated them, explored temples and imagined a sophisticated society of kings, priests, nobles, artisans and farmers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1e/75/1e7597fa-435b-4767-b00f-2ed76ade7424/nov2023_h04_zelianuttall.jpg)

Zelia was welcomed into the international community of anthropologists in Mexico. She and Nadine traveled in the Yucatán with the young American anthropologist Alfred Tozzer, where they were beset by frequent rain and terrible roads. Arriving tired and wet in a small town, Tozzer, who would one day chair Harvard’s department of anthropology, was impressed by the women’s resilience. “Imagine the picture,” he wrote to his family on April 8, 1902. “Mrs. Nuttall, never accustomed to roughing it, a woman entertained by the crowned heads of Europe, sitting at a bench with the top part of my pajamas on drinking chocolate and her daughter with a flannel shirt of mine on doing the same.”

After a few months, Zelia and her daughter returned to Mexico City and purchased a mansion they called Casa Alvarado, in the upscale suburb of Coyoacán. The grand house never failed to impress. Frederick Starr, an anthropologist from the University of Chicago, was one of many who found the palace beautiful and restful: “We rode out to Coyoacán where we found Mrs. Nuttall and her daughter really charmingly situated. The color decoration is simple and strong. Nasturtiums are handsomely used in the patio and balcony effects. … While Mrs. Nuttall dressed, Miss Nuttall showed us through the garden, where a real transformation has been effected.”

Living in Mexico energized Zelia. In addition to her affiliation with Harvard, she had funding to travel and collect artifacts for the Department of Anthropology at the University of California. “With me here, in touch with the government and people, I think that American institutions can but profit and that I can do some good in advancing Science in this country,” she confided to Putnam.

Impressed by her knowledge of the country’s past, public officials and foreign visitors came to see her and listened carefully as she led them around her home and garden, explaining the collection she was busy assembling. Her garden, patio and verandas were home to an increasingly large number of stone artifacts, a beautiful carving of the serpent god Quetzalcóatl, revered for his wisdom, among them. She took up “digging” near Casa Alvarado, an activity one guest later recalled fondly. “Every morning after breakfast Mrs. Nuttall would give me a trowel and a bucket. She herself was equipped with a sort of short-handled spade, and we would go out into the surrounding country and ‘dig.’ We mostly found broken pieces of pottery, but she seemed to think some of them were significant, if not valuable. … She was a very handsome woman and very charming. She lived in great style, with many Mexican servants.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5d/84/5d84dbd3-ce15-47af-8f2a-e88515e24d1c/nov2023_h05_zelianuttall.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/be/d6/bed6df3a-7afc-4f3c-84f7-be65244d3af6/nov2023_h03_zelianuttall.jpg)

Zelia continued to travel throughout the country. She found a 14-page codex painted on deerskin, with commentary in Nahuatl, that she believed so valuable that she bought it with her own money, selling some of her possessions to afford it. “Owing to my residence here I must keep it a profound secret that I possess and sent out of the country this Codex,” she wrote to Putnam.

While she was not above smuggling treasures out of Mexico, Zelia also worked in the National Museum, contributing to its displays and archives, and she became an honorary professor of the institution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cf/db/cfdb0e75-c71f-4afa-8cc5-060522e5eae1/nov2023_h02_zelianuttall.jpg)

Her Sunday teas at Casa Alvarado were a study in salon orchestration. “She would have 30 or 40 people and she would change the groups she invited,” one visitor recalled. “Sometimes they were all people who knew each other. Or else she would bring people together she wanted to introduce to each other. They weren’t like old-style Mexican parties, with all the women on one side and men on the other. The men and women were mixed together.”

According to an oft-repeated legend, at one of her soirées, she advanced to welcome an eminent guest just as her voluminous Victorian drawers came loose and dropped to her ankles. She calmly stepped out of them and proceeded as if nothing had happened. Zelia was, above all, self-confident.

Zelia Nuttall left Mexico during the early months of 1910 and did not return to her beloved Casa Alvarado for seven years. Throughout that time, Mexico was in the midst of a violent revolution. As many as two million people lost their lives in the ten-year conflict, and the country’s infrastructure was reduced to tatters. Even after the end of the most extensive violence, turmoil erupted sporadically until the late 1920s.

By then, visitors to Casa Alvarado agreed that Zelia was rooted in a bygone era. She was a middle-aged woman with thick glasses who favored shawls, laces and jet beads. Her palace was still filled with stuff only a Victorian could accumulate, but Mexico was telling new stories about itself.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/5a/7c5ab860-e36d-4e12-82c2-c8b651de5dda/nov2023_h01_zelianuttall.jpg)

The elites of the previous generation had asserted that descendants of the Aztec, Maya and other civilizations deteriorated into poverty and abandon. Young artists and intellectuals now rejected this belief. In Diego Rivera’s vast public murals, he showed the people of Mexico being ground into poverty and submission by Spanish conquistadors, a rapacious church, foreign capitalism, the army and cruel politicians. Quetzalcóatl replaced Santa Claus at the National Stadium; Chapultepec Park hosted Mexico Night.

Zelia did not like the revolution and she did not approve of what came after it. She did not celebrate the masses; she believed in hierarchy and a natural order of classes and races. Yet she was determined to be relevant to a new era in Mexico. Casa Alvarado became a meeting place for politicians, journalists, writers and social scientists from Mexico and abroad, many of whom came to witness the possibilities of change in the aftermath of a people’s revolution.

Nevertheless, the stubborn elegance of Casa Alvarado in the 1920s was clear testimony that Zelia was not willing to give up her lifestyle. When the French American painter Jean Charlot was a guest at one of Zelia’s teas, he was aghast at the Mexican servants in white gloves.

When Zelia Nuttall died in 1933, the U.S. consul in Mexico City wrote to Nadine—by then a 51-year-old widow living in Cambridge, England—assuring her that they’d given her mother a tasteful funeral. “Your Mother was very highly thought of here, as evidenced by the floral offerings and the number of her friends who came to the funeral service at the cemetery, it being estimated that about one hundred persons were present.”

By that time, the field of anthropology was dramatically changing, becoming more systematic and organized. Those who entered the field in the 1920s and 1930s built expertise in the classroom and under supervision in the field, passing a variety of tests and milestones determined by academic experts and acquiring a credential as proof of the right to pursue these inquiries. With these rigorous new standards, they asserted their superiority as scholars over those of Zelia’s generation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/47/ac/47ac0bb3-d363-4524-ad80-38fde4716eea/nov2023_h15_zelianuttall.jpg)

Yet Alfred Tozzer, in his memorial in the journal American Anthropologist, reflected that Zelia “was a remarkable example of 19th-century versatility.” She was wrong in some of her overarching theories. For instance, she fallaciously argued that ancient Phoenician travelers had carried their culture to Mesoamerica. But she was right about many other things. Through her letters, articles and books, we can trace what she got right and what she got wrong as a scholar, and we can follow her as she moved from one research obsession to the next.

Her private life is harder to grasp. Among all the artifacts, there is little about the quips and gossip she exchanged with friends, the piano music she liked to play and sing. We cannot know what was in the boxes of papers in the cellar of Casa Alvarado that were burned in the housecleaning undertaken by its new tenants. We cannot retrieve personal and public documents lost in the San Francisco earthquake in 1906.

What we do know is that she had to make sacrifices, often very personal ones. We can feel her vulnerability, uncertainty, anger and embarrassment in the letters she wrote, as well as her self-assuredness. It required unusual self-discipline to learn so many languages and to gain a mastery of ancient pictographs. Her almost constant travels imperiled her health even while they advanced her vast network of friends, colleagues and patrons. But she continued to work, and that work helped establish the foundation on which many others now build.

A single mother pursuing a career while looking after a family in a man’s world: In some ways, Zelia Nuttall was a very modern woman.

Adapted from In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations by Merilee Grindle, published by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2023 by Merilee Grindle. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(699x796:700x797)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/23/b6/23b6fe53-d635-4e65-a8c7-07a841b3ba6d/opener2.jpg)