How the Death of George Floyd Sparked a Street Art Movement

A group of Minnesota faculty and students is documenting and archiving the phenomenon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/8e/f78ed963-d4d4-4d32-b756-650652e66e39/82fa1e2200daddfecfb71a0d1fe558f3.jpg)

In March 2020, the Urban Art Mapping research team, a small group of faculty and students from the University of St. Thomas in Saint Paul, Minnesota, was busy conducting interviews with community members of Midway, a bustling, diverse neighborhood. Located in the middle of a six-mile stretch between downtown Saint Paul and downtown Minneapolis along University Avenue, Midway is a formerly white working-class neighborhood that has recently seen an influx of African and South Asian immigrants. Working in Midway for more than a year, our team had been documenting and mapping tags, buffs, stickers, murals—any sanctioned or unsanctioned art in the neighborhood’s built environment. We had recently shifted to interviewing in order to understand what community members thought about the art in their community.

When the global pandemic was announced in March, we were unsure of how it might affect our work. By March 16, our university had announced all classes would be moving online, campus would be closed and all in-person research was being shut down as a result of the worsening coronavirus situation. About two weeks later, the governor of the state of Minnesota announced an order requiring all residents to remain in their homes. Eventually we realized that we could resume our interviews online, but art historian Heather Shirey, one of the three faculty directors of the team, had an idea for another project we could work on while staying inside. Suspecting that a global occurrence like a pandemic would spark the production of urban art worldwide, she knew it would be important to collect images of as much of that art as possible and keep them all in one location for purposes of education and research. As a result, the Covid-19 Street Art database was born in response to this once in a lifetime occurrence, and we immediately got to work soliciting images of street art from all around the world.

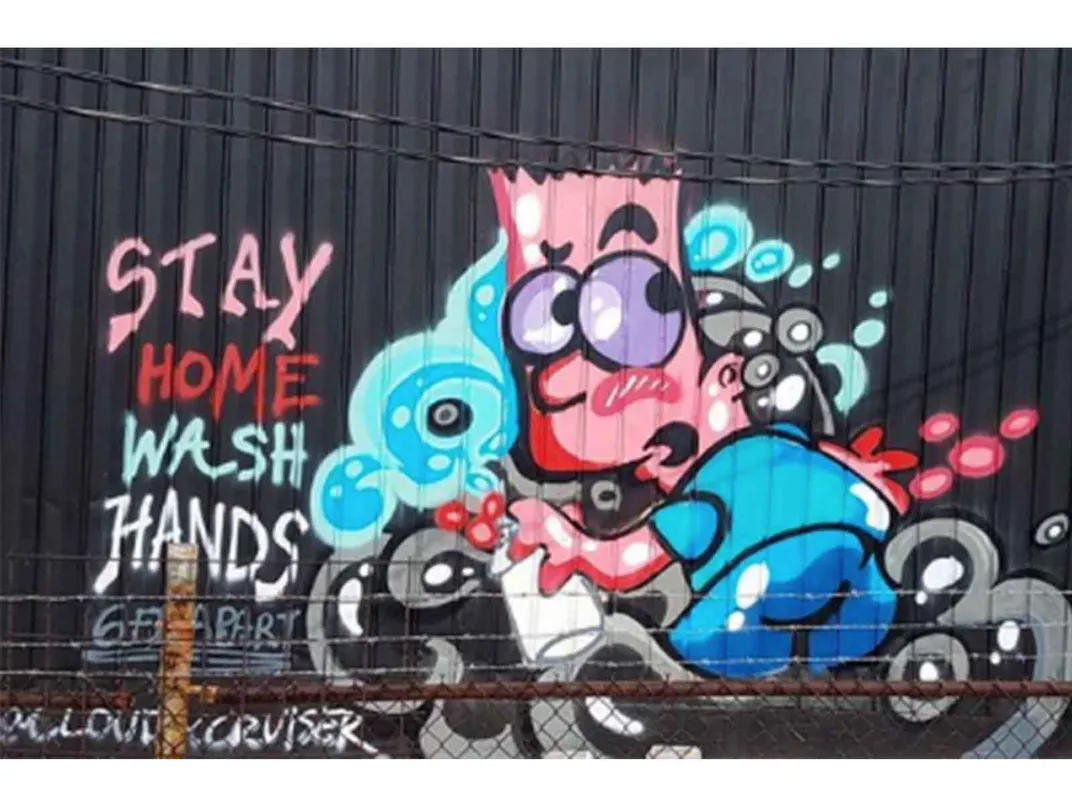

Artists and writers producing work in the streets—including tags, graffiti, murals, stickers, and other installations on walls, pavement and signs—are in a unique position to respond quickly and effectively in a moment of crisis. Street art’s ephemeral nature serves to reveal very immediate and sometimes fleeting responses, often in a manner that can be raw and direct. At the same time, in the context of a crisis, street art also has the potential to transform urban space and foster a sustained political dialogue reaching a wide audience, particularly when museums and galleries are shuttered or are generally inaccessible to much of the public. For all of these reasons, it was not surprising to see an explosion of street art around the world created in response to the COVID-19 global pandemic, even as people’s movement in public spaces was limited due to public health concerns.

Our team continued to work online conducting interviews and collecting COVID-19 art that was being sent to us from all over the world—all in the midst of a global pandemic. Then on May 26 something happened that changed everything: George Floyd was murdered by police officers right before our eyes.

The widely shared video of George Floyd's killing at the hands of Derek Chauvin and three other Minneapolis police officers, in which Mr. Floyd is heard repeating, “I can’t breathe,” and calling out “Mama” to his deceased mother while Chauvin kneels on his neck for over eight minutes, became the driving force of protests and civil unrest. Local uprisings took place not only in Minneapolis, where the murder had occurred, but also in the Midway neighborhood of Saint Paul, where we had already conducted so much of our research. This movement, inspired by George Floyd, sparked a massive proliferation of spontaneous art to appear right in our own backyard. Tags and murals were suddenly everywhere in Minneapolis and Saint Paul. It was an amazing artistic expression of rage, pain, mourning and trauma and someone needed to document it.

On June 5 our team publicly launched the George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art database. As a multiracial and multi-generational team of researchers, we realized we had the knowledge and experience to help preserve the art of a movement that had started in our own community. We would soon find ourselves playing an important part of documenting what might be the largest global explosion of street art addressing one single event or subject in history.

The George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art database is an archive that seeks to document examples of street art from around the world that have emerged in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd as part of an ongoing movement demanding social justice and equality. The database serves as a repository for images and we hope it will be a future resource for scholars and artists by way of metadata (contextual information) that is freely available to anyone curious enough to look. In addition, the project will make possible an analysis of the themes and issues that appear in street art of this movement, explored in relation to local experiences, responses, and attitudes.

While the database started small, it has grown exponentially over time, just as the movement gained cultural and political power. In places like the Twin Cities, where we are, the uprising has served to connect people to each other and provide energy for ongoing emotional and political artistic expression; it has also provided the material conditions for that expression to proliferate. In response to and in anticipation of property damage from civil unrest, thousands of plywood boards were erected to cover windows and doors across the cities. It is the art that appeared on these boards in our city that has, in part, inspired much of the art in other cities across the country and around the world.

Given the global scope of our database and the extremely ephemeral nature of art on boards and writing in the streets, crowdsourcing is essential to the expansion of this project. Our method of collecting these works of art differs from traditional archivists because we have not collected the majority of the pieces in our database ourselves. We rely on the public to take pictures of art that they see and submit them to us. Community engagement is the cornerstone of all we do and when we are able to get community members to play an active role it not only benefits us as a team, but it gets people thinking about the complexities of artistic expression. We have never met many of the people who send us images in person, and we might never get to meet them. Their contributions, however, are central to our ability to document the art of this movement in such an expansive way.

Contributors to our database might live down the street or around the corner from us or they might live on the other side of the world. What matters is that they recognize the importance of the art they encounter in their worlds and the art itself reflects a concern with issues that connect us all to each other. Take, for example, this portrait of George Floyd painted on the wall in the West Bank near Bethlehem. Floyd’s portrait overlays a map with Houston, Texas, where he grew up, prominently marked. Though we don’t know the artist’s identity, we can assume that that person believed the image would resonate for a local audience living in a much different cultural context than that of either Minneapolis or Houston. For us, this image demonstrates the power of artistic expression to transcend place, time and culture. This helps explain how images referring to a murder that happened in Minneapolis could pop up and have impact for people living in places all around the world.

Looking forward, we hope the George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art database can serve the research and educational purposes of students, teachers, scholars and artists. Whenever possible we have included the names of individuals and groups responsible for creating these works, and all reproduction rights for images remain with the artists and/or photographers.

Oftentimes when important historical events like the death of George Floyd and the subsequent uprising take place, public memory and historical narratives get watered down, or in this case “Minnesota-fied”—the way people in our state tend toward a positive perception of things, often sanitizing or ignoring realities that conflict with our generally progressive reputation. As a country as well, we tend to privilege narratives that don’t conflict with positive perceptions we have of ourselves. Certain ideas about what has happened might be more palatable because they don’t implicate us personally in what took place. These attitudes can affect what art is valued and what is not. When this happens, parts of the story can be left out.

As researchers we simply want to try to collect as much of all the art as possible—from the potentially offensive to the inspiring and uplifting. We believe that walls speak, that everything from the most violent and confrontational tag to the most beautiful and positive mural is a legitimate representation of real experience and emotion. Our database serves as a raw and real collection of anti-racist street art created in the heat of the moment with no filter. Our goal is not to create or decide history, but simply to document in a way that maintains the art’s authenticity.

As a multiracial research team, we also want to reserve spaces for BIPOC artists. We envision the database as a place where their work will be protected and preserved. However, we include all art relevant to the movement regardless of who created it, where it is, what it looks like, or what it says. Believing that walls speak means we must consider much more than beautiful, large murals and sanctioned pieces to be artwork; we also believe that the “random” graffiti you see on the streets is as important as the large “aesthetic” murals in telling the truth of the times, if not more so.

Chioma Uwagwu is a 2020 graduate from the University of Saint Thomas in St Paul, MN. She holds degrees in American Culture and Difference as well as Communication Studies. Her research interests include the intersections of race, gender and sexuality in media, particularly film, TV and advertisements. She has been a member of the Urban Art Mapping Project since its conception in 2018.

Tiaryn Daniels is a rising senior at the University of St. Thomas, where she majors in International Studies with an Economics focus and minors in Business. Combining her love of justice, community, and art, she has been a member of the Urban Art Mapping Project for two years. Tiaryn hopes to go to law school after graduating.

David Todd Lawrence is Associate Professor of English at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, MN, where he teaches African-American literature and culture, folklore studies, ethnographic writing, and cultural studies. His writing has appeared in Journal of American Folklore, Southern Folklore, The Griot, Open Rivers, and The New Territory. His book, When They Blew the Levee: Race, Politics and Community in Pinhook, Mo (2018), co-authored with Elaine Lawless, is an ethnographic project done in collaboration with residents of Pinhook, Missouri, an African American town destroyed during the Mississippi River Flood of 2011.

Images can still be submitted directly to either the Covid-19 Street Art database or the George Floyd and Anti-Racist Street Art database using a smartphone or other device.