To Rep. John Lewis, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture was more than simply a building. As he explained during the museum’s September 2016 dedication ceremony, “It is a dream come true.”

This sentiment was both an acknowledgement of the century-long campaign to establish a repository of black history on the National Mall and a deeply personal reflection on the time the congressman and civil rights icon, who died Friday at age 80, spent fighting for the museum’s creation. “I introduced the museum bill in every session of Congress for 15 years,” he wrote. “Giving up on dreams is not an option for me.”

Today, the museum is arguably Lewis’ “biggest legacy,” ensuring “that the millions of people who come to the Mall will now see America in a different light,” says Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III.

“The passing of John Lewis marks a signal moment in the history of our country,” adds Spencer Crew, interim director of the African American History Museum. “Called both the compass and the conscience of the Congress, his influence as a moral and political leader is almost impossible to measure. I had the profound honor and good fortune to be part of Congressman Lewis’ last pilgrimage to honor the Selma to Montgomery march. That March and a young John Lewis’ brutal beating catalyzed the passage of the Voting Rights Act. The Congressman was a lifelong catalyst for justice.”

Christopher Wilson, director of experience design at the National Museum of American History’s African American History Program, also underscores the African American History Museum’s centrality in Lewis’ legacy: “The museum exists. And I think that is a tribute to not only John Lewis’ perseverance, . . . but also his understanding that history, in a different but similarly powerful way as nonviolent direct action, [is] power.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/3a/733a85d9-189a-4a56-8392-b3aa227f77a7/2016_157_6_001.jpg)

Lewis’ contributions to American society spanned more than 60 years of activism and political leadership. He participated in (and in some cases spearheaded) such major civil rights efforts as student sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Freedom Summer and the Selma March. In 1987, he was elected to the House of Representatives as the congressman for Georgia’s 5th District—an office that earned him the title of “the conscience of a nation.” In 2011, President Barack Obama awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Last December, Lewis announced plans to undergo treatment for Stage 4 pancreatic cancer. In a statement, he said: “I have been in some kind of fight—for freedom, equality, basic human rights—for nearly my entire life. I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/2b/412b5d59-1879-4910-8c92-50f96bac3a1c/2016_157_18_001.jpg)

The son of sharecroppers, Lewis was born in Troy, Alabama, on February 21, 1940. As a child, he aspired to be a preacher, famously honing his craft by delivering sermons to chickens. But his passions soon shifted to activism, and at age 18, he traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, for a personal meeting with Martin Luther King Jr.

Just under two years later, Lewis—then a student at Fisk University in Nashville—was jailed for participating in a sit-in against segregation. His arrest on February 27, 1960, marked the first of more than 40 in his lengthy career of activism.

“We grew up sitting down or sitting in,” Lewis told the Tennessean in 2013. “And we grew up very fast.”

In 1961, the 21-year-old volunteered as a Freedom Rider, traveling across the South in protest of segregated bus terminals. Lewis was the first of the original 13 to face physical violence for attempting to use “whites-only” facilities, but as he later reflected: “We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal. We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had to make up our minds not to turn back.”

Alongside King and minister Jim Lawson, Lewis was one of the most notable advocates of the philosophy of nonviolent action. He didn’t simply adopt it as a tactic, according to Wilson, but rather “took those lessons . . . deep into his heart,” embodying “Gandhian philosophies” in all walks of life.

As chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lewis was the youngest of the “Big Six” behind the 1963 March on Washington. Prior to his death, he was the event’s last surviving speaker.

Though King was just 11 years older than Lewis, many viewed him as the representative of an older generation. “To see John Lewis full of righteous indignation and youthful vigor inspired so many other people who were young to participate in the movement,” says Bunch.

Lewis’ commitment to nonviolence was readily apparent during an event later known as “Bloody Sunday.” On March 7, 1965, he was among some 600 peaceful protesters attacked by law enforcement officers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

“The national news that night showed the horrific footage of a state trooper savagely beating him with a nightstick,” Bunch says in a statement. “But it also showed Mr. Lewis, head bloodied but spirit unbroken, delaying a trip to the hospital for treatment of a fractured skull so he could plead with President [Lyndon B.] Johnson to intervene in Alabama.”

One week after the incident, Johnson offered the Selma protesters his support and introduced legislation aimed at expanding voting rights.

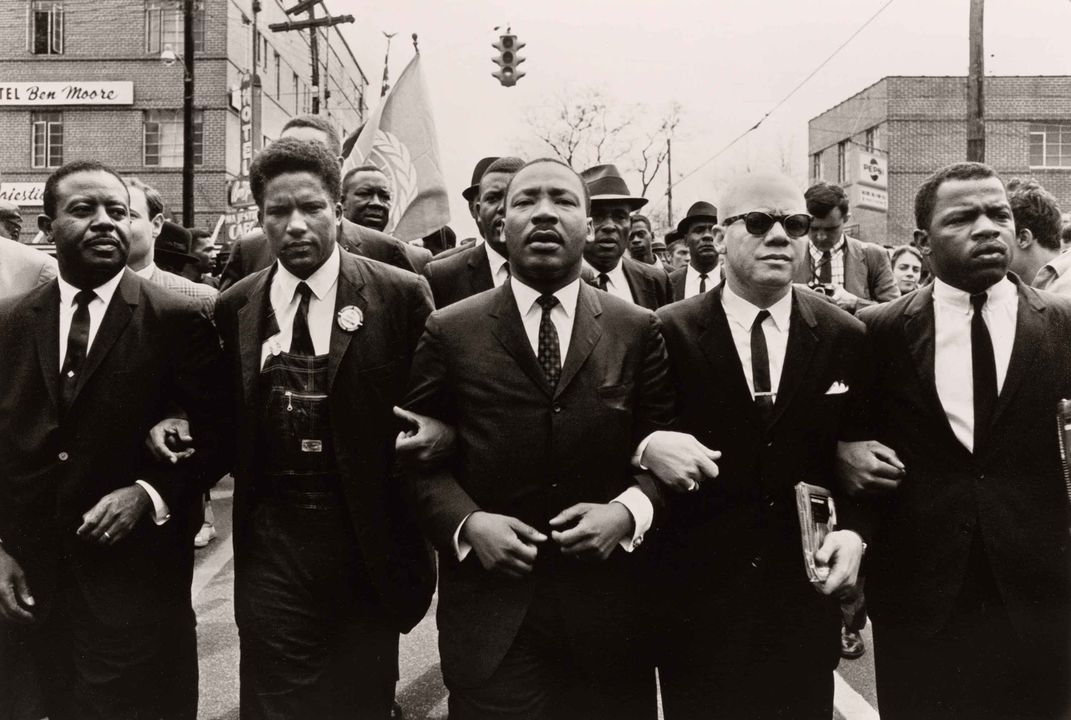

A photograph of the Selma March in the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery’s collections depicts Lewis, King and other civil rights leaders standing arm in arm. “Not only are they showing their solidarity,” says the gallery’s senior historian, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, “ . . . but they’re also creating this wall of people in front of the photographers to show that power, show the strength, show the linkage and that unbroken resolve to keep moving forward.”

The five men’s attire is critical to the portrait’s message: All don suits and ties—clothes “strongly associated with respectability, with masculine power,” Shaw adds. “[This] very specific uniform . . . communicates the aspiration for a social position, the aspiration for a kind of respectability that was often denied black men in the 1960s.”

During the 1970s and ’80s, Lewis shifted gears to the political sphere. After an unsuccessful run for Congress in 1977, he spent several years directing President Jimmy Carter’s federal volunteer agency, ACTION. Elected to the Atlanta City Council in 1981, he soon made another bid for Congress; this time, his efforts were successful.

Over the years, some observers questioned the apparent incongruity between Lewis’ position as a legislator and his defiance of the law as an activist. His response, according to Wilson, was that certain laws were unjust and needed to be broken to effect change. But he emphasized the fact that these rules were still the law, and “if you break those laws, there are consequences.” Adds Wilson, “You have to be willing not only to put yourself out there and make the change, but [to] take responsibility” for the repercussions. Lewis himself adhered to this philosophy of “good trouble” by continuing to attend protests—and undergo arrest—during his time as a congressman.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/0f/6d0ffae0-fd56-4f9a-93a7-0502b4f1a670/ev_oca_20160924_01_331.jpg)

Lewis’ political career found him fighting “for the rights of women, for the homeless, for the less fortunate,” says Bunch, “so in some ways, [he] is the best example of what the civil rights movement was all about, which was ensuring freedom not just for African Americans, but for all Americans.”

Perhaps the most significant legislative victory of Lewis’ 17 terms in Congress was the passage of a 2003 bill establishing the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Lewis worked closely with Bunch, who served as the museum’s founding director before assuming leadership of the Smithsonian, to build it from the ground up.

“He would sit down with me and help me plot strategy, how do you get the support you need, how are you as visible as you need to be,” Bunch explains. “He was involved spiritually and strategically in almost all aspects of the museum.”

In the congressman’s own words, the museum stands “as a testament to the dignity of the dispossessed in every corner of the globe who yearn for freedom.” As Bunch observes, he spoke about it “as if it was the culmination of the civil rights movement, one of the most important things that he had helped shepherd during his career. . . . His notion that helping to make this museum a reality was the fulfillment of dreams of many generations was just so moving to me and so meaningful.”

Lewis’ activism continued through the end of his life. After protests against police brutality and systemic racism broke out in response to the May 25 killing of George Floyd, Lewis released a statement calling for his fellow Americans “to fight for equality and justice in a peaceful, orderly, non-violent fashion.” In June, he visited Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, D.C. and reflected on the current moment in an interview with New York magazine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/f2/f3f254e1-f4c2-476d-997b-fdf47b4cc428/gettyimages-1218336892.jpg)

“No, I don’t have any regrets,” Lewis told New York in reference to his move from activist to elected official. “I feel sometimes that there’s much more that we can do, but we’ve got to organize ourselves and continue to preach the politics of hope, and then follow our young people, who will help us get there. And we will get there. We will redeem the soul of America. We will create the loving community in spite of all of the things that we witness.”

Though he was arguably the most prominent surviving leader of the civil rights movement, Lewis always emphasized the contributions of others over his own. His commitment to creating the African American History Museum was emblematic of this mindset, says Bunch: “He understood the power of remembering that the stories were not just of him or of Dr. King, but of people who were famous only to their family. . . . Part of [his] legacy is this sense of recognizing that all kinds of people play a role in shaping a nation and leading change.”

Bunch adds, “That humble nature, that sense of generosity, is really what makes John Lewis special, and that in a way, we are a much better country because of his vision, his leadership and his belief in this nation.”

Echoing this sentiment, Crew concludes, “Beyond any single act, John Lewis will be remembered as a beacon of courage, dignity, and commitment to the highest ideals of the human spirit. His legacy will endure for the ages.”

Read the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s statement on John Lewis’ passing and the National Portrait Gallery’s In Memoriam tribute.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/ae/48aefc11-2948-4ad3-8740-d9f63b5dd8db/2012_107_19.jpg)

:focal(360x94:361x95)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/a1/fea1a6fa-4a9a-49b4-a209-f4d96e8547d4/lewis_mobile.png)

:focal(731x200:732x201)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/f1/96f1f037-646b-4c37-acc8-231e460a9ed8/john_lewis_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/5d/435d46fd-10d4-4f9e-8cd7-feff09bad8ac/2011_14_5.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/44/dc4414c9-1474-4817-9d0e-c49735a84684/2011_14_13.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/04/d904a075-7ea4-42ed-ac73-72089c07ee64/2011_14_12.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)