An Astronomer’s Paradise, Chile May Be the Best Place on Earth to Enjoy a Starry Sky

Chile’s northern coast offers an ideal star-gazing environment with its lack of precipitation, clear skies and low-to-zero light pollution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/58/a1/58a13a6e-8f56-4feb-a7fb-38c2e83cc150/42-57433134.jpg)

The view through the eyepiece of the telescope is breathtaking. Like tiny diamonds on black velvet, countless sparkling stars float against a fathomless backdrop of empty space. “This is Omega Centauri,” says astronomer Alain Maury, who runs a popular tourist observatory just south of San Pedro de Atacama in northern Chile. “To the naked eye, it looks like a fuzzy star, but the telescope reveals its true nature: a huge, globular cluster of hundreds of thousands of stars, almost 16,000 light-years away.” I could take in this mesmerizing view for hours, but Maury’s other telescopes are trained at yet more cosmic wonders. There’s just too much to see.

Chile is an astronomer’s paradise. The country is justly famous for its lush valleys and snowcapped volcanoes, but its most striking scenery may be overhead. It is home to some of the finest places on Earth to enjoy the beauty of the starry sky. If there’s one country in the world that really deserves stellar status, it’s Chile.

If you live in a city, as I do, you probably don’t notice the night sky at all. Yes, the moon is visible at times, and maybe you can see a bright planet like Venus every now and then, but that’s about it. Most people are hard-pressed to recognize even the most familiar constellations, and they’ve never seen the Milky Way.

Not so in Chile. A narrow strip of land, 2,700 miles long and 217 miles at its widest point, Chile is tucked between the Andes Mountains to the east and the Pacific to the west. It stretches from the arid Atacama Desert in the north to the stark granite formations of the Torres del Paine National Park in the south. Large parts of Chile are sparsely populated, and light pollution from cities is hardly a problem. Moreover, the northern part of the country, because of its dry desert atmosphere, experiences more than 200 cloudless nights each year. Even more important to stargazers, Chile provides a clear view of the spectacular southern sky, which is largely invisible from countries north of the Equator.

Long before European astronomers first charted the unknown constellations below the Equator, just over 400 years ago, the indigenous people of Latin America knew the southern sky by heart. Sometimes their buildings and villages were aligned with the heavens, and they used the motions of the sun, the moon and the stars to keep track of time. Their night sky was so brilliant that they even could recognize “dark constellations”— pitch-black, sinuous dust clouds silhouetted against the silvery glow of the Milky Way. The Inca dark constellation of the llama is particularly conspicuous, as I noticed during my visit to Maury’s observatory.

It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that Western astronomers were drawn to Chile, in a quest for the best possible sites to build Southern Hemisphere observatories. Americans and Europeans alike explored the mountainous regions east of the port of La Serena, a few hundred miles north of the country’s capital, Santiago. Horseback expeditions lasting for many days—back then, there were no roads in this remote part of the world—took them to the summits of mountains like Cerro Tololo, Cerro La Silla and Cerro Las Campanas, where they set up their equipment to monitor humidity (or lack thereof), sky brightness and atmospheric transparency.

Before long, astronomers from American institutions and from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) erected observatories in the middle of nowhere. These outposts experienced their heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, but many of the telescopes are still up and running. European astronomers use the 3.6-meter (142 inches) telescope at the ESO’s La Silla Observatory to search for planets orbiting stars other than the sun. A dedicated 570-megapixel camera attached to the four-meter (157 inches) Blanco Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory is charting dark matter and dark energy—two mysterious components of the universe that no one really understands.

If you’re star trekking in Chile, it’s good to know that most professional observatories are open for tourists one day each week, usually on Saturdays. Check out their schedules in advance to prevent disappointment—the drive from La Serena to La Silla may take almost two hours, and the curvy mountain roads can be treacherous. I once got my four-wheel-drive pickup truck in a spin while descending the gravel road from Las Campanas Observatory, a scary ride I hope never to repeat. Also, dress warm (it can be extremely windy on the summits), wear sunglasses and apply loads of sunblock.

Most professional observatories are open to visitors only during daytime hours. If you’re after a nighttime experience, the region east of La Serena—especially Valle de Elqui—is also home to a growing number of tourist observatories. The oldest is Mamalluca Observatory, some six miles northwest of the town of Vicuña, which opened in 1998. Here amateur astronomers give tours and introductory lectures, and guides point out the constellations and let visitors gaze at stars and planets through a number of small telescopes. Everyone can marvel at the view of star clusters and nebulae through the observatory’s 30-centimeter (12 inches) telescope.

You can look through a 63-centimeter (25 inches) telescope at Pangue Observatory, located ten miles south of Vicuña. At Pangue, astronomy aficionados and astrophotographers can set up their own equipment or lease the observatory’s instruments. Farther south, near the town of Andacollo, is Collowara Observatory, one of the newest tourist facilities in the region. And south of La Serena, on the Combarbalá plain, is Cruz del Sur Observatory, equipped with a number of powerful modern telescopes. Most observatories offer return trips to hotels in Pisco Elqui, Vicuña or Ovalle. Tours can be booked online or through travel agents in town.

I will never forget my first look at the Chilean night sky in May 1987. I was awed by the glorious constellations of Scorpio and the Southern Cross, the star-studded Milky Way with its many star clusters and nebulae, and of course the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds (two companion galaxies to our own Milky Way). Using today’s digital equipment, all of this can be captured on camera. Little wonder that professional astrophotographers have fallen in love with Chile. Some of them have the privilege of being designated photo ambassadors by ESO: They get nighttime access to observatories, and their work is promoted on the ESO website.

Every traveler to Chile interested in what’s beyond our home planet should visit—and photograph—the country’s Norte Grande region. It’s a surrealistic world of arid deserts, endless salt flats, colorful lagoons, geothermal activity and imposing volcanoes. East of the harbor town of Antofagasta, the Atacama Desert looks like a Martian landscape. In fact, this is where planetary scientists tested the early prototypes of their Mars rovers. The alien quality of the terrain makes you feel as if you’re hiking on a forbidding yet magnificent planet orbiting a distant star.

The 45-mile gravel road that took me through the rock-strewn Atacama from Ruta 5 (Chile’s main highway) to Cerro Paranal during my first visit there in 1998 has since been paved, providing much easier access to the ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT)—one of the foremost professional astronomical observatories in the world. Here, 8,645 feet above sea level, astronomers enjoy the serene spectacle of sunset above the Pacific Ocean before they switch on the four huge 8.2-meter (323 inches) Unit Telescopes, which are equipped with high-tech cameras and spectrographs that help them unravel the mysteries of the universe. And yes, even this temple of ground-based astronomy is open to visitors only on Saturdays.

A couple hundred miles to the northeast, tucked away between the Cordillera de la Sal mountain range and the Altiplano on the border with Argentina, is the oasis of San Pedro de Atacama. The region was inhabited thousands of years before the Spanish conquistadors built the first adobe houses and a Roman Catholic church in the 17th century—one of the oldest churches in Chile. Today San Pedro is a laid-back village, populated by backpackers and lazy dogs. It serves as the hub for exploratory trips to the surrounding natural wonders, from the nearby Valle de la Luna to the remote El Tatio geyser field.

Even though electric street lighting was introduced in San Pedro some ten years ago, it’s hard to miss the stars at night. A few steps into a dark side road will give you an unobstructed view of the heavens. Don’t be surprised, while you’re sipping a pisco sour in one of the many restaurants in town, to hear American, European or Japanese visitors talk about the big bang, the evolution of galaxies, or the formation of stars and planets. Over the last couple of years, San Pedro has become a second home for the astronomers of the international ALMA observatory.

ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) is the latest addition to Chile’s professional astronomical facilities. It’s one of the highest (altitude: 16,40 feet) and largest ground-based observatories in the world, with 66 antennas, most of them 12 meters (40 feet) across. The actual observatory, at the Llano de Chajnantor, some 30 miles southeast of San Pedro, is not open to tourists, but on weekends, trips are organized to ALMA’s Operations Support Facility (OSF), where you can visit the control room and take a look at antennas that have been brought down for maintenance. On clear days the OSF offers stunning views of nearby volcanoes and over the Salar de Atacama salt flat. While ALMA studies invisible radiation from distant stars and galaxies, San Pedro also affords many opportunities for old-fashioned stargazing. Some fancy resorts, like Alto Atacama and Explora, have their own private observatories where local guides take you on a tour of the heavens.

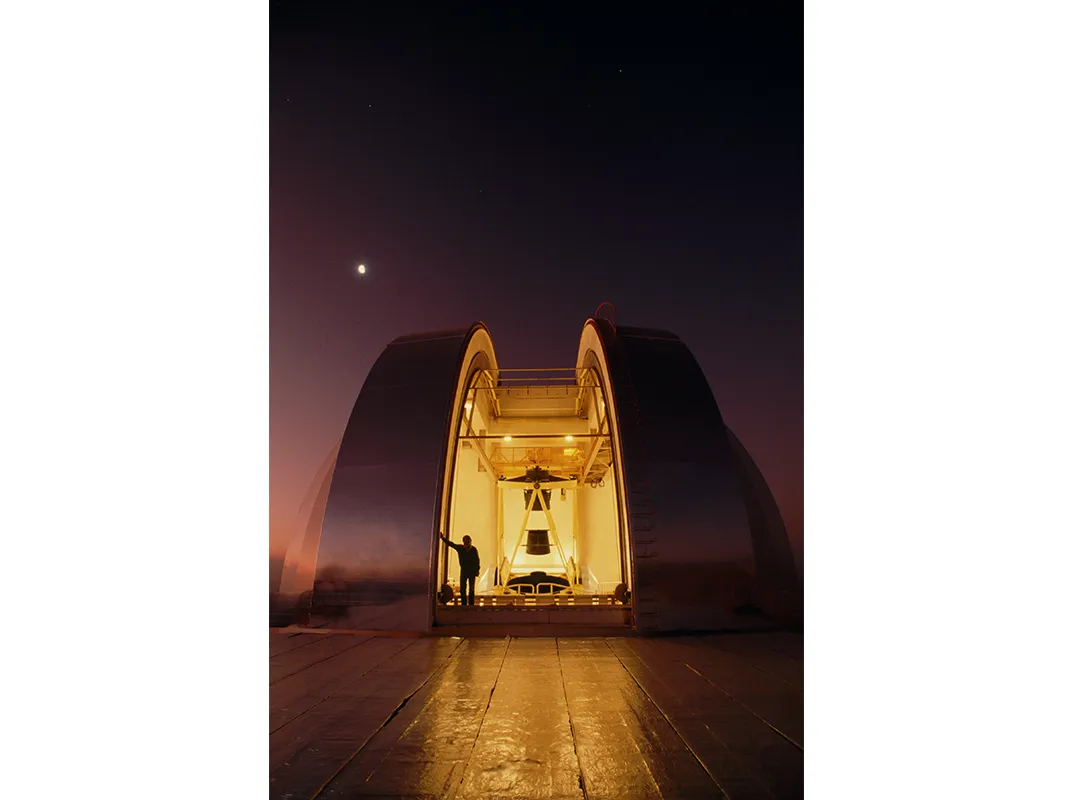

But if you really want to immerse yourself in the Chilean night sky, I strongly recommend a visit to SPACE, which stands for San Pedro de Atacama Celestial Explorations. Here, French astronomer and popularizer Maury and his Chilean wife, Alejandra, welcome you with hot chocolate, warm blankets and entertaining stories about the history of astronomy before they take you to their impressive telescope park.

It was here that I got my first look at the globular cluster Omega Centauri. I marveled at the clouds of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, binary stars, softly glowing nebulae, glittering groups of newborn stars and distant galaxies. Suddenly the world beneath my feet turned into an inconspicuous speck of dust in a vast, incredibly beautiful universe. As the famous American astronomer Carl Sagan once said: “Astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience.” The Chilean night sky touches your deepest self.

For professional astronomers, Chile will remain the window to the universe for many years to come. On Cerro Las Campanas, plans are in place to build the Giant Magellan Telescope, featuring six 8.4-meter (330 inches) mirrors on a single mount. Meanwhile, the European Southern Observatory has chosen Cerro Armazonas, close to Paranal, as the site for the future European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT). This monster instrument—which would be the largest optical/near-infrared telescope ever built—will have a 39-meter (128 feet) mirror consisting of hundreds of individual hexagonal segments. It is expected to revolutionize astronomy, and it may be able to detect oxygen and methane—signs of potential life—in the atmospheres of Earthlike planets orbiting nearby stars.

In 2012 I drove the bumpy trail to the summit of Armazonas, and took a small stone for a souvenir. Two years later the mountaintop was flattened by dynamite to create a platform for the E-ELT. One day I hope to return, to see the giant European eye on the sky in its full glory. But well before the telescope’s “first light,” Chile will beckon me again, to witness the wonder of a total solar eclipse, both in July 2019 and in December 2020.

I have to admit I’m hooked. Hooked by the cosmos, as seen and experienced from the astronomical paradise of Chile. You’ll understand when you go there and see for yourself. Who knows, one day we may run into each other and enjoy the view together.