Pat’s King of Steaks juts out on a triangle corner in South Philadelphia’s East Passyunk neighborhood, across the street from rival restaurant Geno’s Steaks. Both local culinary institutions claim credit for popularizing or perfecting one of the nation’s most famous sandwiches: the Philly cheesesteak. But only Pat’s has the distinction of a historical marker.

“When people think of Philadelphia, they think cheesesteak, the Rocky statue and maybe that bell with the crack in it,” jokes Pat’s owner, Frank Olivieri. While he has deep respect for the city’s oft-heralded 18th- and 19th-century history, Olivieri feels more recent events in Philadelphia, particularly food history, often get short shrift. “A lot of it gets overlooked,” he says. “Just because [other things] happened in the 1700s doesn’t mean something that happened in 1930”—the year Olivieri’s great-uncle Pat Olivieri invented the cheesesteak—“isn’t historic.”

The Pat’s historical marker was installed in 2008, proudly placing the cheesesteak within American and global culinary history. Cast in aluminum with raised black lettering on a light gray background, it follows the instantly recognizable sign-on-a-stick form shared by thousands of historical markers across the United States. Yet one characteristic sets this marker apart: Olivieri put it up himself, enlisting historian Celeste A. Morello to write the text. Erected without involvement from state or local historical organizations, the sign speaks to the chaotic system of overlapping interests surrounding such markers. As Olivieri says, “I’m not going to stand around and wait for someone else to pat me on the back.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9f/8b/9f8bb7f5-72e3-4326-af47-ad5edc5799d9/service-pnp-highsm-56200-56227v.jpeg)

When it comes to historical markers, the hidden truth is this: In any given state, as many as ten or more entities could be putting up signs at the same time. Decades ago, states typically had just one official marker program. Now, many more state, local and private entities, each with their own policies and processes, regularly erect markers. The bizarre reality is that anyone with a few thousand dollars and a place to put a marker can get one saying whatever they want. Given broad similarities in design, it’s difficult to tell who’s responsible for the more than 185,000 markers recorded in the Historical Markers Database—a volunteer-run online catalog that’s arguably the most comprehensive resource of its kind—without a close inspection.

As the director of research at the American Association for State and Local History (AASLH), I’ve found myself wondering who exactly historical markers benefit. Why do we put them up? And, in an age when so much information is available on our cellphones, why should anyone care about them?

To fully grasp the nature of historical marker programs, you must first understand the country’s state and local history ecosystem. Recent findings from the AASLH indicate history organizations are deeply connected to government agencies, more so than other entities in the arts and culture sector. As scholars Carole Rosenstein and Neville Vakharia wrote in a 2022 report, “Public history is maintained through a partnership between government and nonprofits. … Many institutions blur the lines between ‘public’ and ‘private,’ defying easy categorization.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cb/44/cb442655-fcc7-4943-9b29-954bea613a3d/battle_of_talladega_historic_marker.jpeg)

This is particularly evident at the state level, where most large historical marker programs are administered. While most states carry out a shared set of functions related to history, offering a museum, library and archives; a historic site system; a historic preservation body; and a historical marker program, the entities responsible for these services can vary widely, even between neighboring states.

Some states, such as Ohio and Nebraska, operate like a one-stop history shop, carrying out most or all of these functions under the banner of a single, mostly government-funded agency. In other states, these same tasks are split across as many as half a dozen public agencies and private nonprofits. In both contexts, the model is distinctly hybrid, with government agency work supplemented by boards of private citizens, volunteers and the nonprofits. Though the shared terminology of “historical society” or “historical commission” suggests some kind of uniformity, you can never quite know whether an office in one state exists in the next state over, or whether two people with essentially the same job title have even remotely similar responsibilities.

The vast majority of states operate some kind of statewide historical marker program. But identifying which agency, commission, museum or society is responsible for it is a guessing game until you get down to specifics. Sometimes the biggest history entity in the state runs the show; other times, it’s the smallest. Sometimes it’s a government agency or commission of some kind, while in other places, the program is run entirely by a private nonprofit. In general, most state marker programs operate with a similar process. Community groups apply for a marker. An entity reviews the applications, then researches and develops text in collaboration with the applicants. Community groups raise money to fund the creation and installation of the marker, whose design must be approved by the state before being sent to an outside manufacturer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/71/99/71997fce-e302-4a0b-a626-76a4d202327c/10011908286_b887ca251c_k.jpg)

Virginia is home to the country’s oldest historical marker program. In 1927, the state began placing roadside markers to document events and people deemed historically important in the corridor between the state capital of Richmond and Mount Vernon, the onetime home and plantation of George Washington. Indicative of the messy nature of state history, the program moved homes several times during the first few decades of its existence. Today, it’s under the umbrella of the government-run Department of Historic Resources, outside the aegis of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture (owned and operated, in turn, by the nonprofit Virginia Historical Society, the state’s oldest cultural institution).

During the middle decades of the 20th century, dozens of other states developed their own statewide marker programs, many of which operated with a similarly dizzying mix of public and private caretakers. By 1976, the year of the U.S.’s bicentennial commemoration—which, among other things, saw an explosion of interest in documenting and preserving local history—states had erected thousands of markers along roadsides, outside county courthouses, on battlefields and in public squares, establishing official recognition of an often-limited view of what counted as historically significant.

Today, this complicated system poses major challenges. For one thing, the shifting responsibility for historical markers over the past half-century has made it difficult for some states to track the locations and content of their signs. In Washington, where stone monuments with plaques are more common than the sign-on-a-stick markers seen elsewhere, the state historical society recently underwent a major audit of its state-sponsored markers, asking residents to upload photos and GPS coordinates when they found relevant displays. “Many [plaques] probably hadn’t been seen in many years,” says Jennifer Kilmer, the society’s director.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a6/ab/a6ab571f-6d7b-4bc3-a4c6-e281a0b215db/4946190425_6a42a43e81_k.jpg)

In New Hampshire, a conflict over a new historical marker made national headlines in May, after Republican state councilors raised objections to a sign honoring Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an early 20th-century labor activist and U.S. Communist Party leader nicknamed the “Rebel Girl.” Following petitions from local community members, both the state Division of Historical Resources and the Concord City Council approved the marker’s installation near Flynn’s birthplace. Days after the groundbreaking ceremony, however, members of the state’s Executive Council spoke out against the plaque, arguing that New Hampshire shouldn’t be honoring communists. Saying the marker had been installed on state rather than city property, Republican Governor Chris Sununu ultimately supported its removal.

This episode was mostly framed in the day’s online conversations as yet another example of conservative Republicans censoring history that doesn’t align with their preferred narratives about the past. Yet it also reveals the complex bureaucratic systems that undergird the administration of history at the state level. Rather than a simple conflict between community residents and the state, the controversy over the marker involved three separate state government entities—the Division of Historical Resources, the Executive Council and the governor’s office—along with the local city council. The disagreement over the marker’s installation and removal ended up being as much about policies and procedures (there is, after all, an official process for requesting the removal or revision of a marker) as it was about the content of the sign itself. Last month, the community activists who petitioned for the marker’s creation filed a lawsuit against the state, arguing that the removal violated both departmental rules and a federal law governing administrative procedure.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fb/bf/fbbf2dc1-efb2-43ea-9348-ee4ef55bc379/elizabeth_gurley_flynn_historical_marker_concord_nh.jpeg)

Partisan politics represents a growing concern for the public agencies administering marker programs. But these groups also face a range of other issues, most notably financial. Statewide history organizations funded as part of the state government are perpetually underresourced, meaning that while many have been putting up markers for nearly a century, few have the capacity (in either staff time or money) to regularly review or revise their content. So, while Americans’ understanding of the past regularly evolves, historical markers don’t, leaving mid-20th-century interpretations locked in for decades. What’s more, as outdoor installations, markers are vulnerable to damage, vandalism and simple environmental degradation. Scotty Kirkland, an employee of the Alabama Department of Archives and History and the chair of the Alabama Historical Association’s marker committee, says that in his state, “we have a lot of ‘car-meets-marker’ situations.”

Without the capacity to regularly review, repair or update markers, states sometimes only realize the need for reinterpretation when communities apply to have a damaged marker replaced or refurbished, says Sandra Clark, director of the Michigan History Center. Unfortunately, these fixes don’t always happen. Even if agencies had the money to fully replace broken or outdated signs, the dwindling number of foundries that manufacture markers, along with persistent supply chain issues, have led to major delays in production of new and revised designs alike. “It’s taking a lot longer now to get markers than it was a few years ago,” Kirkland says.

As if all of this—complex state bureaucracies, funding challenges, politics, supply chains—wasn’t complex enough, the nation’s historical marker landscape has more overlapping programs than ever before. In the mid-20th century, a single statewide program typically oversaw markers. Today, local, regional and topical organizations all coexist, from county-level historical commissions to African American heritage trails to programs specific to the Revolutionary War and the Civil War.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/77/33/77336ac4-d79c-4477-be6e-46bf21d44adc/pine_grove_marker.jpeg)

The William G. Pomeroy Foundation, one of the few national philanthropic organizations directly funding historical markers, provides support for both official statewide marker programs and more localized efforts to erect historical markers outside the official system. According to Deryn Pomeroy, the foundation’s director of strategic initiatives, the organization sees its efforts as an opportunity to help communities “instill a pride of place,” as well as to “tell stories that might not be eligible for a state marker in their state.”

Each marker program can have different areas of focus, different processes for approval and different standards for what qualifies as significant. Without a centralized marker-making authority, it’s easier for less “official” markers to slip through, using a shared aesthetic with properly vetted markers to sneak in other kinds of interpretations. In 2015, for instance, the New York Times reported that Donald Trump had installed a historical marker commemorating a Civil War battle that never actually happened on a golf course he owned in Virginia.

Independently erected markers, even when put up in good faith, challenge efforts to discuss historical markers as part of a cohesive system. Ahead of the U.S.’s upcoming 250th anniversary, the Daughters of the American Revolution have started erecting new markers across the country in collaboration with local chapters of the nonprofit. The twist is that each plaque presents the same text, commemorating “Revolutionary War Patriots” and, in doing so, defying the more common location-specific nature of historical markers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a9/10/a910da6b-8db8-499b-adea-d71b0f0ceb68/15236578319_7401af4fde_4k.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8c/34/8c345524-fc65-4d80-9ab5-eee08a2107d9/mackenzoe.jpg)

While historical markers have a distinctly old-school vibe—particularly in an age of augmented reality, virtual tours and online programming—they continue to be important expressions of community history and values. Indeed, though anyone could erect a marker themselves, for the most part they do not, instead seeking the distinction of recognition through an official program. In recent years, those traditional statewide marker programs have begun efforts to expand the stories forged on historical markers to ensure they present a complete version of the state’s history.

Alabama, for example, began its History Revealed project in 2021, directly funding historical markers documenting underrepresented aspects of local history. “We’ve been in the marker business since the 1950s,” Kirkland says. “The first generation of markers that was erected told only one version of Alabama’s history.” In 2021 and 2022, the state fully funded five new markers through the program, with plans to continue this work in the future. Beyond the History Revealed markers, more groups across the state are applying for signs that share new dimensions of Alabama history. “The type of marker [applications] I’m getting now are different, in a good way,” Kirkland says.

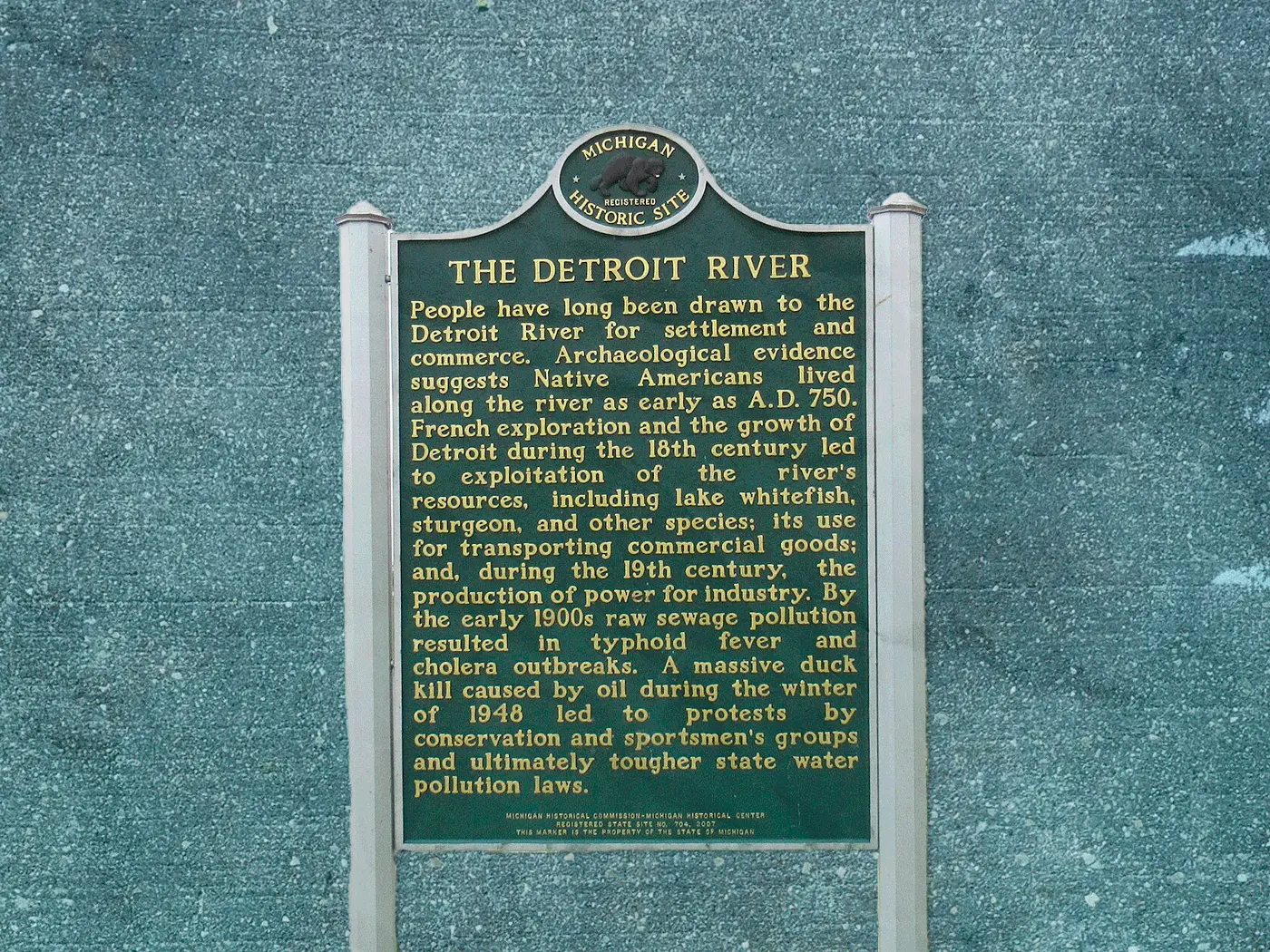

Michigan, meanwhile, has used funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to create new historical markers in Detroit. Michigan History Center staff brought together members of community groups representing the full diversity of the city, asking them to assess existing markers and collectively identify people, events and stories that should be added to the city’s commemorative landscape. “We really strongly believe that the grassroots nature of this program is an essential part of it,” Clark says. “We wanted communities that had not thought of markers as something that belonged to them to get involved.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/dd/54/dd5472ff-d779-4c41-b99d-89ab9bbcd43a/44741587190_ad4fad8257_k.jpg)

The Washington State Historical Society, meanwhile, has used its monuments project not to put up new markers but rather to assess and reinterpret existing ones. According to Kilmer, the society’s director, many of Washington’s early markers focused on the activities of the region’s first white settlers, to the exclusion of much older histories of the state’s Native population. Through its new effort, Kilmer says, the group has committed to evaluating the current marker landscape and asking, “Do these match the current values of the historical society?”

In each of these examples, the state has shifted the focus of its marker programs to better include a wider range of community voices and ensure that markers the state supports reflect a full vision of history. Instead of a wholesale re-envisioning of the purpose of historical markers, this shift reflects a recommitment to the power these displays wield to shape the public’s ideas about history.

In my conversations about historical markers, I’ve come to realize that these installations don’t just serve as opportunities to learn new facts as you walk through a neighborhood or drive through unfamiliar terrain. Perhaps more than anything, the role of government in erecting historical markers serves as validation: saying in an official capacity that a certain person or story matters.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cd/d9/cdd91868-d747-4d2e-b2bb-5c75a5c5969d/bellstreetterminal-marker.jpeg)

“[Markers’] role in validating people’s history and people’s past is extraordinary,” says Clark. “They are kind of a mark that says, ‘Yes, your history was important. You are part of this community.’” Even though anyone can raise money and install a marker privately, most groups want an official stamp of approval that says their story is significant. The presence of a marker doesn’t just signal that something happened here; it indicates that a community is invested in passing that history on to others and has dedicated the substantial time and effort required to garner state support of its commemoration. Or, as Kirkland puts it, “Markers are a reflection of the people that helped to erect them.”

Although the processes of obtaining a state-endorsed marker can be complex, the final product is an expression of a community’s civic life. Each marker erected is the result of years of community organizing, fundraising, research, patience and persistence. As statewide marker programs shift focus to ensure the state’s commemorative landscape represents a more complete history, their community engagement efforts are essential to the process.

The next time you see a marker, don’t think of it as a simple educational display. Instead, remember the time and effort that went into its creation. It’s an effort to say, “This history matters to us, and we hope it matters to you, too.”