In Defense of the Blobfish: The ‘World’s Ugliest Animal’ Is Our Fault

The distinguished blobfish has been judged unfairly

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Blobfish-ugly-470.jpg)

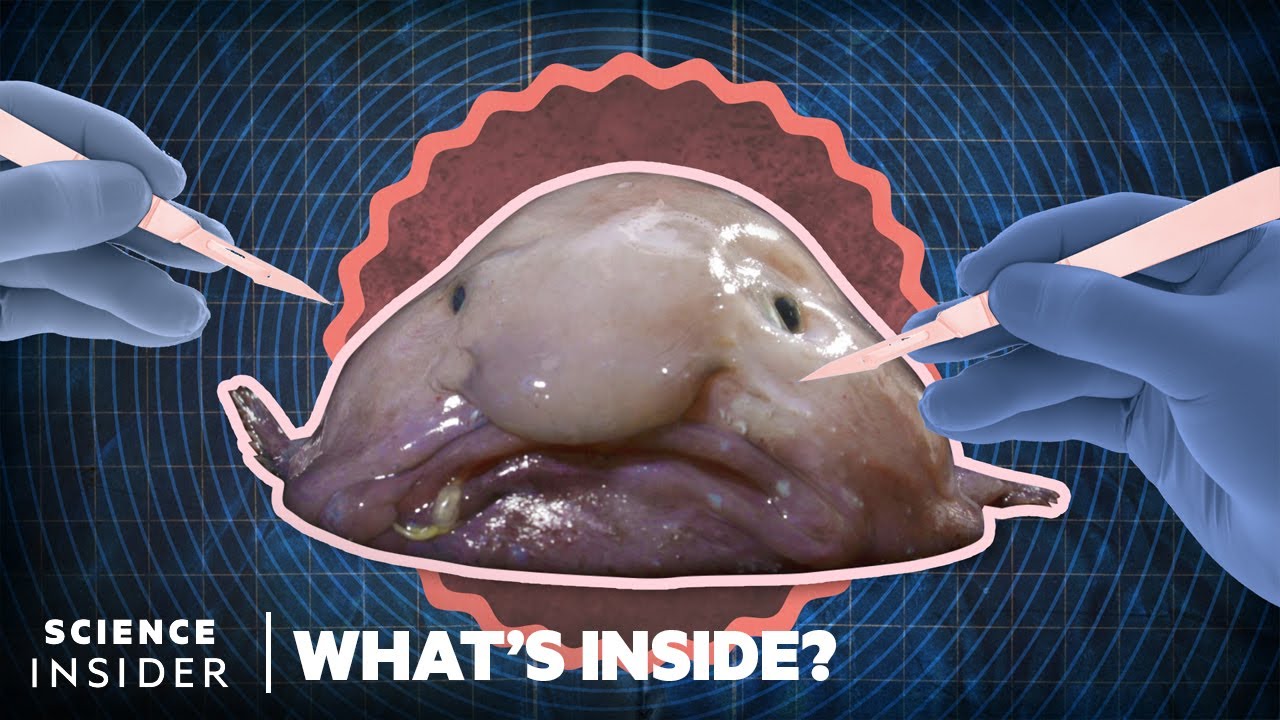

The blobfish—that frowning pile of goop up there—was once crowned the world’s ugliest animal. The run-off was led by the Ugly Animal Preservation Society. In 2013, the Ugly Animal Preservation Society chose the blobfish as its champion for all the animals out there whose unappealing visages garner them less support then their cute and cuddly brethren. As the Society said at the time: “The panda gets too much attention.”The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has called it a “floppy water balloon,” the BBC likened it to an ’80s dessert, and The Guardian designated it “a marine Jabba the Hut.”

They’re right. And since the unsightly creature was first photographed in 2003, it’s been the target of an anthropic bullying fest. But would people be so quick to laugh at the great Psychrolutes marcidus if they knew its pink, jelly-like appearance was in fact the work of human beings?

The blobfish are deep-sea fish. Part of the fathead sculpin family—a piscine class of tadpole-shaped bottom-dwellers—they mainly live off the coast of Australia, guarding the depths of the ocean, around 4,000 feet below the waves. Due to the weight of the ocean above, the water pressure down there is over 100 times the air pressure we experience on land. You wouldn’t want to be lurking at such a depth without a very secure submarine. Likewise, the blobfish really doesn’t like being up here.

Blobfish are built for deep

Many fish have something called a swim bladder—an air-filled organ that helps them move around and stay buoyant. If one removes a fish with a swim bladder from their homey depths, the volume of the gases in their air sac will expand with the lightening water pressure, writes Adrienne Calo for KQED. Those gases can force the bladder to such a size that it crushes the fish’s other vital organs, killing it.

The blobfish is different. It has no swim bladder, as little buoyancy is required for a life largely spent laying on the ocean floor (we feel you, bud). That means when the blobfish is brought into shallow waters, it doesn’t die the way other deep-sea fish do. But it does transform.

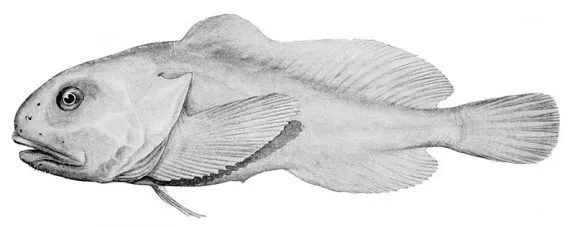

See, the blobfish possesses other unique anatomy to enable undersea thriving. It has a sparse skeleton made of very weak bones, because strong bones take energy to develop, according to Insider Science. And instead of red muscle, the strong stuff, the blobfish has an abundance of white muscle, which allows it to swim in short bursts to catch prey. Its soft tissue is logged with water and fat, which both protects the fish from surrounding pressure and enables it to move easily across the sand. Notably, the blobfish has no scales. The “loose and flabby” skin covering its entire body is weak and pliable, but an apt container at the bottom of the ocean. When observed at home, the blobfish looks like a fish: It’s no Nemo, but its blue-grey, slightly spiky body looks like what you’d expect of a deep-water swimmer.

“No pressure” is no good

But sometimes, a blobfish minding its business on the seafloor finds itself swept up in a net, pulled to the surface by trawling fishermen. Only then, tugged away from its natural habitat, do the blobfish’s attributes betray it. Relieved of the high pressure of the depths, which hold the fish together, its water-logged tissue collapses into a traumatized, gelatinous mass. This is the state it is forced to debut before us air-breathers.

So, who are we to laugh at the body we’ve created by interference? Who are we to call it the drunken work of evolution?

Let’s see you descend 4,000 feet below the ocean’s surface. Your body would implode. Your organs would be crushed, and you’d probably be reduced to some sort of paste. Meanwhile, the blobfish beside you—relaxed, naturally equipped—would look on handsomely.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8b/2b/8b2baae0-c2c7-4f0b-bcee-adb24b9362bf/psychrolutes_phrictus_1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sonja_headshot.png)