How the Key to the Bastille Ended Up in George Washington’s Possession

A gift from an old friend is one of Mount Vernon’s most fascinating objects

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/ff/43ff01e6-77e2-4b93-9525-466127b67f4f/bastille-key-resized.jpg)

President George Washington knew how to curate a blockbuster exhibit—and with just one artifact. Elite visitors who mingled in August 1790 at his New York reception, a meet-and-greet of sorts, clustered around an extraordinary sight: a midnight-colored metal key, just over seven inches in height and a little more than three inches wide, a key that once sealed the king’s prisoners into the notorious Bastille prison of Paris.

Following Washington’s party, newspapers across the country ran an “exact representation” of the key, splayed out in grim silhouette. This “new” relic of the French Revolution, sent by Washington’s longtime friend, the Marquis de Lafayette, soon appeared on display in Philadelphia, hung prominently in the president’s state dining room. (The legislation moving the nation’s capital from New York to a federal district, situated along the Potomac River, passed in 1790; Philadelphia was the interim capital until 1800.)

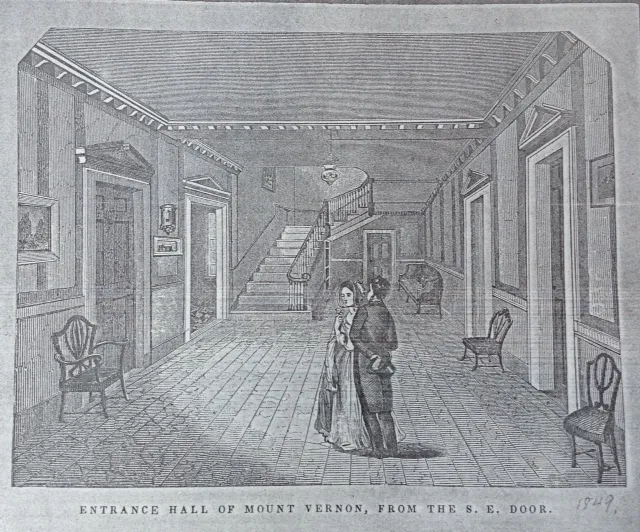

To the first American president, the Bastille key came to represent a global surge of liberty. He considered the unusual artifact to be a significant “token of victory gained by Liberty over Despotism by another.” Along with a sketch of the Bastille by Etienne-Louis-Denis Cathala , the architect who oversaw its final demolition, the key hung in the entryway of Washington’s Virginia estate, Mount Vernon. How and why it landed in the president’s home makes for a fascinating tale.

We can map the key’s trail across the Atlantic by following the busy footsteps of several revolutionaries who corresponded as crisis shadowed the French political scene. These writers, a mixed set of radicals who spanned the Republic of Letters, watched events unfold in Paris (the failure of the Assembly of Notables’ reforms, popular uprisings, and bread riots) with equal parts fascination and concern.

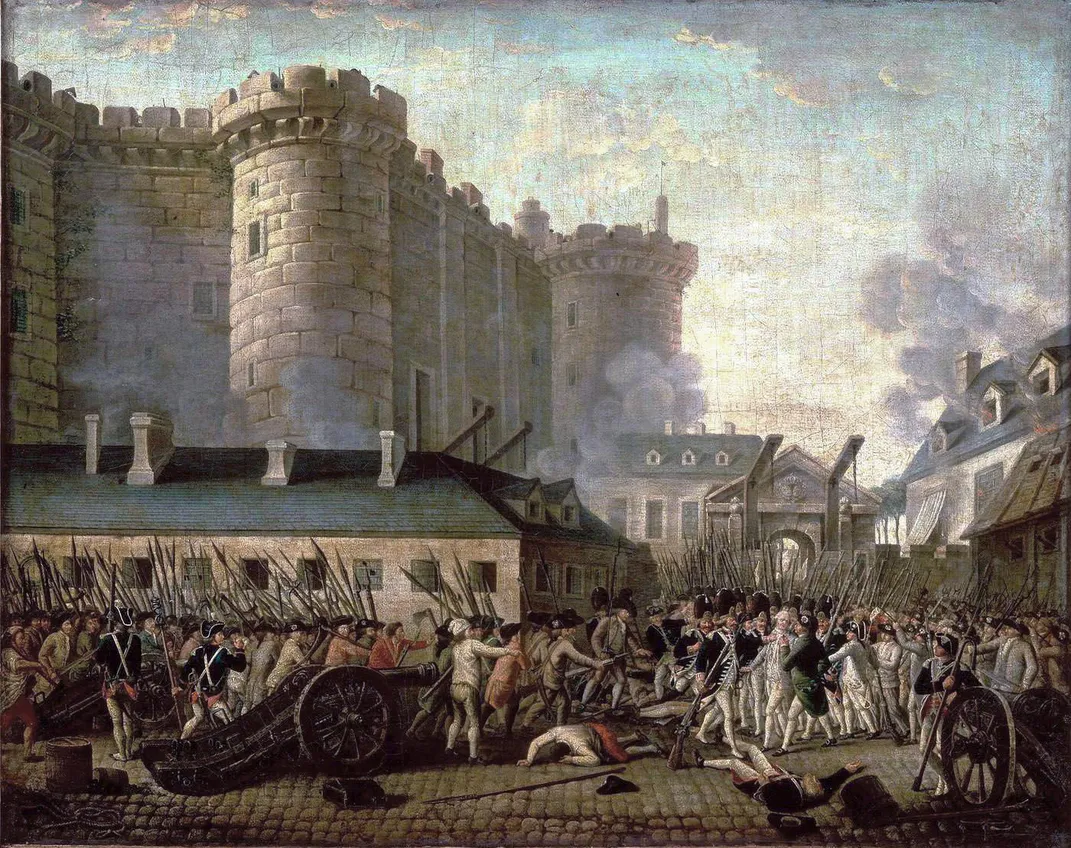

As the onset of the French Revolution convulsed the city, daily life dissolved into chaos. On July 14, 1789, a surge of protesters stormed the medieval fortress-turned-prison known as the Bastille. Low on food and water, with soldiers weary from repeated assault, Louis XVI’s Bastille was a prominent symbol of royal power—and one highly vulnerable to an angry mob armed with gunpowder. From his two-story townhouse in the Ninth Arrondissement, the Virginian Thomas Jefferson struggled to make sense of the bloody saga unspooling in the streets below.

He sent a sobering report home to John Jay, then serving as Secretary for Foreign Affairs, five days after the Bastille fell. Even letter-writing must have felt like a distant cry—since the summer of 1788, Jefferson had faithfully dispatched some 20 briefings to Congress, and received only a handful in reply. In Jefferson’s account, his beloved Paris now bled with liberty and rage. Eyeing the narrowly drawn neighborhoods, Jefferson described a nightmarish week. By day, rioters pelted royal guards with “a shower of stones” until they retreated to Versailles. At evening, trouble grew. Then, Jefferson wrote, protesters equipped “with such weapons as they could find in Armourer’s shops and private houses, and with bludgeons…were roaming all night through all parts of the city without any decided and practicable object.”

Yet, despite his local contacts, Jefferson remained hazy on how, exactly, the Bastille fell. The “first moment of fury,” he told Jay, blossomed into a siege that battered the fortress that “had never been taken. How they got in, has as yet been impossible to discover. Those, who pretend to have been of the party tell so many different stories as to destroy the credit of them all.” Again, as Jefferson and his world gazed, a new kind of revolution rewrote world history. Had six people led the last charge through the Bastille’s tall gates? Or had it been 600? (Historians today place the number closer to 900.)

In the days that followed, Jefferson looked for answers. By July 19, he had narrowed the number of casualties to three. (Modern scholars have raised that estimate to roughly 100.) Meanwhile, the prison officials’ severed heads were paraded on pikes through the city’s labyrinth of streets. With the Bastille in ruins, the establishment of its place in revolutionary history—via both word and image—spun into action. Like many assessing what the Bastille’s fall meant for France, Thomas Jefferson paid a small sum to stand amid the split, burnt stone and view the scene. One month later, Jefferson returned. He gave the same amount to “widows of those who were killed in taking the Bastille.”

At least one of Jefferson’s close friends ventured into the inky Paris night, bent on restoring order. Major General Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, a mainstay at Jefferson’s dinner table, accepted a post as head of the Paris National Guard. As thanks, he was presented with the Bastille key.

Attempting to send the key and Bastille sketch to his former general in the United States, Lafayette planned to entrust it to Thomas Paine, the Common Sense author and English radical. With Europe wracked by political upheaval, Paine’s travel plans suddenly changed. Ultimately, the two artifacts reached Mount Vernon thanks to the efforts of a cosmopolitan South Carolinian: John Rutledge, Jr., Jefferson’s travel companion and protégé.

Despite honing his military experience in the American Revolution and elsewhere, Lafayette’s prediction for the future of France was cloudy at best. With the sketch and key, he sent Washington an unabridged account of life in Paris, now both a home front and battle zone. “Our Revolution is Getting on as Well as it Can With a Nation that Has Swalled up liberty all at once, and is still liable to Mistake licentiousness for freedom,” Lafayette wrote to Washington on March 17, 1790. Then he added:

“Give me leave, My dear General, to present you With a picture of the Bastille just as it looked a few days after I Had ordered its demolition, with the Main Kea of that fortress of despotism—it is a tribute Which I owe as A Son to My Adoptive father, as an aid de Camp to My General, as a Missionary of liberty to its patriarch.”

Throughout the 19th century, visitors descended on Mount Vernon and marveled at the object. Several keen observers noticed that the key showed a “hard wrench” or two in the handle’s wear. Next to bank-keys, others thought, the Bastille artifact seemed fairly unremarkable. It was, one Victorian tourist sniffed, “a very amiable key” but “no means mysterious enough for a dissertation.” But for the elderly Marquis de Lafayette, touring the familiar grounds of Mount Vernon on his farewell tour in 1824-25, the Bastille key still moved history in his memory. An ocean away from the Bastille, Lafayette searched for his sign of liberty in Washington’s front hall, and found it where the general left it.

Today's visitors can still see the Bastille key hanging aloft in the central hall of George Washington's Mount Vernon, and even carry home a reminder of Lafayette's legacy from the gift shop.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)