Why the Titanic Still Fascinates Us

One hundred years after the ocean liner struck an iceberg and sank, the tragedy still looms large in the popular psyche

Dorothy Gibson—the 22-year-old silent film star— huddled in a lifeboat, dressed in only a short coat and sweater over an evening gown. She was beginning to shiver.

Ever since it had been launched, at 12:45 a.m., Lifeboat 7 had remained stationed only 20 yards away from the Titanic in case it could be used in a rescue operation. Dorothy and her mother, Pauline, who had been traveling with her, had watched as lifeboat after lifeboat left the vessel, but by just after 2 o’clock it was obvious that the vast majority of its passengers would not be able to escape from the liner. Realizing that the ship’s sinking was imminent, lookout George Hogg ordered that Lifeboat 7 be rowed away from the Titanic. The risk of being sucked down was high, he thought, and so the passengers and crew manning the oars rowed as hard as they could across the pitch-black sea. Dorothy could not take her eyes off the ship, its bow now underwater, its stern rising up into the sky.

“Suddenly there was a wild coming together of voices from the ship and we noticed an unusual commotion among the people about the railing,” she said. “Then the awful thing happened, the thing that will remain in my memory until the day I die.”

Dorothy listened as 1,500 people cried out to be saved, a noise she described as a horrific mixture of yells, shrieks and moans. This was counterpointed by a deeper sound emanating from under the water, the noise of explosions that she likened to the terrific power of Niagara Falls. “No one can describe the frightful sounds,” she remembered later.

Before stepping onto the Titanic, Dorothy Gibson had already transformed herself from an ordinary New Jersey girl into a model for the famous illustrator Harrison Fisher—whose lush images of idealized American beauty graced the covers of popular magazines—and then into a star of the silent screen.

By the spring of 1912, Dorothy was feeling so overworked that she pleaded with her employers at the Éclair studios in Fort Lee, New Jersey, to grant her a holiday. The days were long, and she realized that, in effect, there was “very little of the glamour connected with movie stars.” She may have been earning $175 a week—the equivalent of nearly $4,000 today—but she was exhausted; she even went so far as to consider quitting the studio. “I was feeling very run down and everyone insisted I go away for a while,” she recalled later. “So Mr. Brulatour made arrangements for me to have a wondrous holiday abroad. It seemed the ideal solution.” (Her married 42-year-old lover, Éclair’s Jules Brulatour, was one of the most powerful producers in the film industry.)

Dorothy and her mother sailed for Europe on March 17, 1912, with an itinerary that was to include not only the capitals of the Continent, but also Algiers and Egypt. However, when they arrived in Genoa from Venice on April 8, they received a telegram at their hotel requesting that Dorothy return to America. An emergency had arisen at the studio; she was needed to start work at once on a series of films. Although she had been away for only three weeks, she had benefited from the change of scene—she said she felt “like a new woman”—and cabled back to tell the studio of her plans. After a brief stopover in Paris, she would sail back to New York from Cherbourg on April 10.

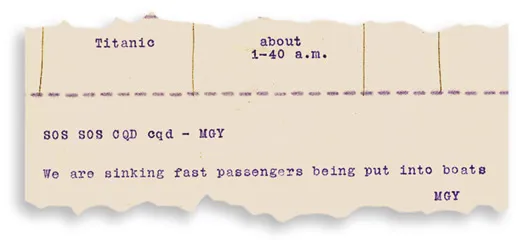

There was silence in the lifeboat. “No one said a word,” recalled Dorothy. “There was nothing to say and nothing we could do.” Faced with the bitter cold and increasingly choppy seas, Dorothy had to acknowledge the possibility that she might not last the night. Had the wireless operators managed to send out a distress signal and call for the help of any nearby ships? The possibility that they could drift for miles in the middle of the harsh Atlantic for days on end was suddenly very real.

As dawn broke on April 15, the passengers in Lifeboat 7 saw a row of lights and a dark cloud of smoke in the distance.“Warming ourselves as best we could in the cramped quarters of the lifeboat, we watched that streak of black smoke grow larger and larger,” recalled Dorothy. “And then we were able to discern the hull of a steamship heading in our direction.”

The men on the lifeboat, now with hands numbed by cold, rowed with extra vigor toward the Carpathia, which had picked up Titanic’s distress signals and had traveled 58 miles in an effort to rescue its survivors. As the sun cast its weak early-morning light across the sea, Dorothy noticed a few green cushions floating in the ocean; she recognized them as being from the sofas on the Titanic. The morning light—which soon became bright and fierce—also revealed the numerous icebergs that crowded around them.

At around 6 o’clock the lifeboat carrying Dorothy Gibson drew up alongside the Carpathia. A few moments later, after she had climbed the rope ladder that had been lowered down from above, she found herself on deck. Still wearing her damp, wind-swept evening gown, Dorothy was approached by Carpathia passengers James Russell Lowell and his wife, and asked whether she would like to share their cabin. After eating breakfast, she retired to their quarters, where she slept for the next 26 hours.

Jules Brulatour had always intended to send a film crew to the pier to record Dorothy’s arrival in New York; he was one of the first to realize that the newsreel could be used as a powerful publicity tool and that the star’s return to America on board the world’s most famous rescue ship would help boost box-office numbers. But suddenly he found himself with an extraordinary story on his hands. Information about the loss of the Titanic was in short supply—initially some newspapers had claimed that all its passengers had survived. Capt. Arthur Rostron of the Carpathia had placed a blanket ban on information from the vessel being leaked to the news media—the wireless service could be used, he said, only for communication with the authorities and for relay of messages between survivors and their families, as well as the task of providing a list of which of the Titanic’s passengers had perished.

As the Carpathia sailed into New York—on the stormy night of Thursday, April 18—it was surrounded by a mass of tiny vessels, all chartered by news corporations desperate to break what would be one of the biggest stories of modern times. From their tugs, reporters shouted through megaphones offering terrific sums of money for information and exclusives, but Captain Rostron said he would shoot any pressmen who dared venture aboard his ship.

However, one of his original passengers, Carlos F. Hurd, was a veteran journalist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and over the course of the past four days he had spoken to many survivors, amassing enough information for a 5,000-word story. Hurd’s only problem was how to get the report off the ship. He managed to send a wireless message to a friend at the New York Evening World, which, in turn, chartered a tug to sail to the Carpathia. Out of sight of the captain, Hurd stuffed his manuscript into an oilskin bag, which he then threw down to the waiting boat. The final edition of the New York Evening World, published on April 18, carried a digest of Hurd’s report, which was published in full the next morning. The story—“Titanic Boilers Blew up, Breaking Her in Two After Striking Berg”—began: “Fifteen hundred lives—the figures will hardly vary in either direction by more than a few dozen—were lost in the sinking of the Titanic, which struck an iceberg at 11:45 p.m., Sunday, and was at the ocean’s bottom two hours and thirty-five minutes after.”

As Dorothy Gibson stood on the deck of the Carpathia, the night was so black that she could hardly make out the skyline of New York. Unknown to her, thousands of people had come out that rainy night to witness the arrival of the Carpathia. Dorothy “ran crying down the ramp” into the arms of her stepfather, soon followed by her mother. Leonard Gibson ushered his stepdaughter and wife through the crowd and into a taxi and whisked them off to a New York restaurant. But there was only one thing on Dorothy’s mind—her lover, Brulatour. She realized that it would have been inappropriate for him to meet her at the pier—this would have given rise to scandal—but she desperately needed to see him. After a couple of hours, she drove to the hotel where she had arranged to meet him.

That night Brulatour presented her with an engagement ring—a cluster of diamonds worth $1,000—and a plan: to make a dramatic one-reel film of her survival. Soon, he said, she would not only be his wife, but she would be more famous than ever before. The loss of the Titanic would make both things possible.

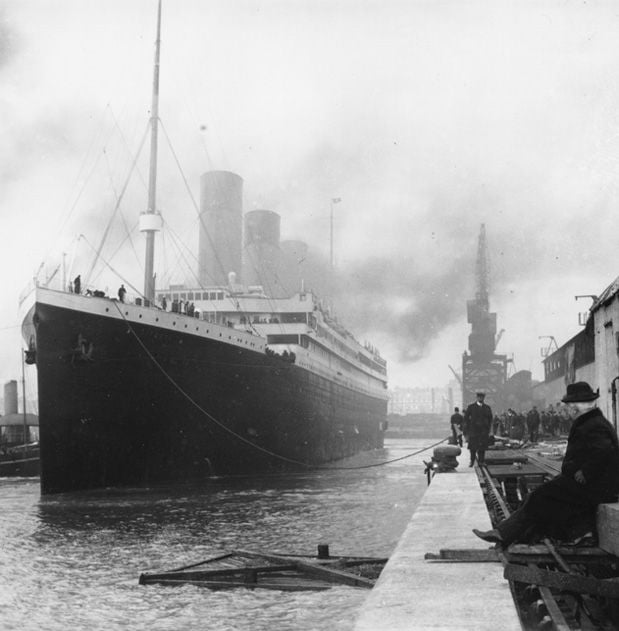

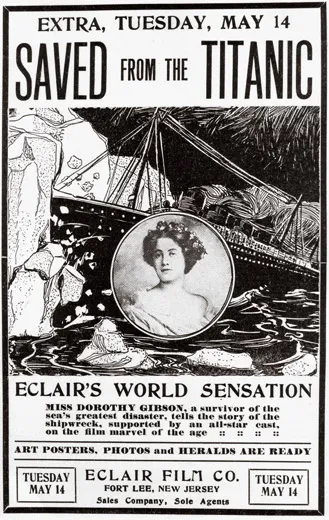

The public’s appetite for information and details—accounts of suffering, bravery, self-sacrifice and selfishness—seemed insatiable, and Brulatour at first took advantage of it by employing the relatively new medium of newsreel. His footage of the docking of the Carpathia—which was spliced together with scenes of Capt. Edward J. Smith, who had been lost in the disaster, walking on the bridge of the Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic, and shots of icebergs from the area where the liner sank, together with images of the launching of the liner—premiered in East Coast theaters on April 22. Not only was Brulatour’s Animated Weekly newsreel “the first on the scene with specially chartered tugboats and an extra relay of cameramen,” according to Billboard magazine, but it also showed that “the motion picture may fairly equal the press in bringing out a timely subject and one of startling interest to the public at large.”

Brulatour hyped the newsreel as “the most famous film in the whole world,” and so it proved, packing theaters across America over the following weeks. The pioneering movie mogul organized a private screening for Guglielmo Marconi—the inventor of the wireless technology that had played a central part in the Titanic story—and gave a copy of the film to President William Howard Taft, whose close friend Maj. Archie Butt had died in the sinking. Spurred on by the success of his Animated Weekly feature, Brulatour decided to go ahead with a silent film based on the disaster, starring his lover, authentic Titanic survivor Dorothy Gibson.

Within a few days of her arrival in New York, Dorothy had sketched out a rough outline for a story. She would play Miss Dorothy, a young woman traveling in Europe who is due to return to America on the Titanic to marry her sweetheart, Ensign Jack, in service with the U.S. Navy.

Shooting began almost immediately at the Fort Lee studio and on location on board a derelict freighter that lay in New York Harbor. She was clad in the same outfit she had worn the night she had escaped the sinking ship—a white silk evening dress, a sweater, an overcoat and black pumps.The verisimilitude of the experience was overwhelming. This wasn’t so much acting, in its conventional form at least, as replaying. Dorothy drew on her memory and shaped it into a reconstruction.

When the film was released, on May 16, 1912, just a month after the sinking, it was celebrated for its technical realism and emotional power. “The startling story of the world’s greatest sea disaster is the sensation of the country,” stated the Moving Picture News. “Miss Dorothy Gibson, a heroine of the shipwreck and one of the most talked-of survivors, tells in this motion picture masterpiece of the enthralling tragedy among the icebergs.” (The actual film no longer survives.)

“The nation and the world had been profoundly grieved by the sinking of the Titanic,” she said, “and I had the opportunity to pay tribute to those who gave their lives on that awful night. That is all I tried to do.” In truth, the experience had left her feeling hollow, disassociated from her reality. Soon after the release of Saved from the Titanic, Dorothy walked out of her dressing room at the Fort Lee studios and turned her back on the movie business. She was, she stated, “dissatisfied.”

At some point during the summer or autumn of 1912—just as Brulatour was forming, with Carl Laemmle, the Universal Film Manufacturing Company, later to become Universal Pictures—Brulatour’s wife, Clara, finally decided to bring the farce that was her marriage to an end. After scandalous and protracted divorce proceedings, Gibson married Brulatour on July 6, 1917, in New York. It soon became obvious that whatever spark they had between them had been kept alive by the illicit nature of the relationship. The couple divorced in 1923.

Dorothy fled to Europe, where her mother had already settled. Ensconced in Paris, she had enough money from her alimony for everyday luxuries such as cocktails and champagne and entertained a wide range of bohemian friends including the writers Colette, H.G. Wells and James Joyce. “Oh my, what a time I am having!” she told a journalist in 1934. “I never cared much for motion pictures, you see, and I am too glad to be free of that work. I tell you it was an immense burden. I have had my share of troubles, as you know, but since coming to France, I have recovered from that and feel happy at last. Who could not be deliriously happy in this country? I have such fun. But I fear it cannot go on like this always. I have had my dream life, and am sure that someday a dark cloud will come and wash it all away!”

The shadow she feared would destroy her dream life was World War II. In May 1940, Dorothy was in Florence to collect her mother and bring her back to France when Germany invaded Holland and Belgium. It would still have been possible for the two women to return to America. The reason they didn’t? Certainly their experience on the Titanic was a factor. “I must say I never wanted to make the Ocean trip to America at this time,” said Dorothy later in an affidavit, “as my mother and I were most timid on the ocean—we had been in a shipwreck—but I also never wanted to stay in Italy, but we just waited in Italy always hoping things would be better to travel.”

Trying to make sense of Dorothy’s life from this point onward is a difficult task. In the spring of 1944, while still in Florence with her mother, she was informed by the questura, the Italian police, that she would be taken to the German-controlled Fossoli internment center. She tried to escape, but on April 16 was arrested and taken to a Nazi concentration camp. After being moved around various camps, she was imprisoned at San Vittore, which she described as a “living death.” It’s most likely that Gibson would have died in this camp had it not been for the machinations of a double agent, Ugo Luca Osteria, known as Dr. Ugo, who wanted to infiltrate Allied intelligence in Switzerland (something he subsequently failed to do). Gibson was smuggled out of the camp under the pretense that she was a Nazi sympathizer and spy. Although the plan worked—she did escape and crossed into Switzerland—the experience left her understandably drained. After interrogation in Zurich, where she gave an affidavit to James G. Bell, vice consul of the American consulate general, she was judged too stupid to have been a genuine spy. In Bell’s words, Dorothy “hardly seems bright enough to be useful in such capacity.”

Dorothy tried to resume a normal life after this episode, but the trauma of her survival—first the Titanic, then a concentration camp—took its toll. After the war ended in 1945, she returned to Paris and enjoyed a few months at the Ritz, where, on February 17, 1946, she died in her suite, probably from a heart attack, at age 56.

The sinking of the world’s most famous ship generated three waves of Titanic mania. The first, as we have seen, hit popular consciousness immediately after the disaster, resulting in Brulatour’s newsreel, Dorothy Gibson’s film Saved from the Titanic, a clutch of books written by survivors, poems like Edwin Drew’s “The Chief Incidents of the Titanic Wreck” (published in May 1912) and Thomas Hardy’s “The Convergence of the Twain” (June 1912), and a flurry of songs (112 different pieces of music inspired by the loss of the Titanic were copyrighted in America in 1912 alone).

The First World War, and then the Second quieted the Titanic storm; the loss of hundreds of thousands of men on the battlefields of Europe, the whole-scale destruction of cities and communities around the world, and Hitler’s single-minded plan to wipe out an entire race of people, together with other “undesirables,” placed the sinking of the ship, with its death toll of 1,500, toward the bottom end of the league of global tragedies.

The mid-1950s is generally considered to represent the second wave of Titanic fever. In the midst of the cold war—when there was a perceived threat that, at any moment, the world could end in nuclear Armageddon—the Titanic represented a containable, understandable tragedy. A mist of nostalgia hung over the disaster—nostalgia for a society that maintained fixed roles, in which each man and woman knew his or her place; for a certain gentility, or at least an imagined gentility, by which people behaved according to a strict set of rules; for a tragedy that gave its participants time to consider their fates.

The first full-scale movie representation of the disaster in the ’50s was a melodrama called simply Titanic, starring one of the ruling queens of the “woman’s picture,” Barbara Stanwyck. She plays Julia Sturges, a woman in the midst of an emotional crisis. Trapped in an unhappy marriage to a cold but wealthy husband, Richard (Clifton Webb), she boards the Titanic with the intention of stealing their two children away from him.

The film, directed by Jean Negulesco, was not so much about the loss of the liner as the loss, and subsequent rekindling, of love. If the scenario—a broken marriage, a devious plan to separate children from their father, a revelation surrounding true parenthood—wasn’t melodramatic enough, the charged emotional setting of the Titanic was used to heighten the sentiment.

It would be easy to assume that the plotline of the abducted children in producer and screenwriter Charles Brackett’s Titanic was nothing more than the product of a Hollywood screenwriter’s overheated imagination. Yet the story had its roots in real life. Immediately after the Carpathia docked in New York, it came to light that on board the liner were two young French boys—Lolo (Michel) and Momon (Edmond)—who had been kidnapped by their father (traveling on the Titanic under the assumed name Louis Hoffman). Fellow second-class passenger Madeleine Mellenger, who was 13 at the time, remembered the two dark-haired boys, one aged nearly 4, the other 2. “They sat at our table . . . and we wondered where their mamma was,” she said. “It turned out that he [the father] was taking them away from ‘mamma’ to America.” In an interview later in his life, Michel recalled the majesty of the Titanic. “A magnificent ship!” he said. “I remember looking down the length of the hull—the ship looked splendid. My brother and I played on the forward deck and were thrilled to be there. One morning, my father, my brother, and I were eating eggs in the second-class dining room. The sea was stunning. My feeling was one of total and utter well-being.” On the night of the sinking, he remembered his father entering their cabin and gently awakening the two boys. “He dressed me very warmly and took me in his arms,” he said. “A stranger did the same for my brother. When I think of it now, I am very moved. They knew they were going to die.”

Despite this, the man calling himself Louis Hoffman—real name Michel Navratil—did everything in his power to help fellow passengers safely into the boats. “The last kindness . . . [he] did was to put my new shoes on and tie them for me,” recalled Madeleine. She escaped to safety with her mother in Lifeboat 14, leaving the sinking ship at 1:30 a.m., but Michel Navratil had to wait until 2:05 a.m. to place his sons in Collapsible D, the last boat to be lowered. Witnesses recall seeing the man they knew as Hoffman crouching on his knees, ensuring that each of his boys was wrapped up warmly.

As he handed his elder son over to Second Officer Charles Herbert Lightoller, who was responsible for loading the boat, Michel stepped back, raised his hand in a salute and disappeared into the crowd on the port side of the ship. His son Michel later recalled the feel of the lifeboat hitting the water. “I remember the sound of the splash, and the sensation of shock, as the little boat shivered in its attempt to right itself after its irregular descent,” he said.

After the Carpathia docked in New York, the two boys became instantly famous. Journalists dubbed the boys the “Orphans of the Deep” or the “Waifs of the Titanic” and within days their pictures were featured in every newspaper in America. Back in Nice, Marcelle Navratil, desperate to know about the fate of her children, appealed to the British and French consulates. She showed the envoys a photograph of Michel, and when it was learned that Thomas Cook and Sons in Monte Carlo had sold a second-class ticket to a Louis Hoffman—a name Navratil had borrowed from one of their neighbors in Nice—she began to understand what her estranged husband had done.

The White Star Line promptly offered their mother a complimentary passage to New York on the Oceanic, leaving Cherbourg on May 8. Only a matter of weeks later, Marcelle Navratil arrived in New York. A taxi took her to the Children’s Aid Society, which had been besieged by photographers and reporters. According to a New York Times account, “The windows of the building opposite were lined with interested groups of shopworkers who had got wind of what was happening across the way and who were craning their necks and gesticulating wildly toward a window on the fifth floor where the children were believed to be.” The young mother was allowed to greet her boys alone. She found Michel sitting in a corner of the room, in the window seat, turning the pages of an illustrated alphabet book. Edmond was on the floor, playing with the pieces of a puzzle.

When she entered, the boys looked anxious, but then, as they recognized their mother, a “growing wonder spread over the face of the bigger boy, while the smaller one stared in amazement at the figure in the doorway. He let out one long-drawn and lusty wail and ran blubbering into the outstretched arms of his mother. The mother was trembling with sobs and her eyes were dim with tears as she ran forward and seized both youngsters.”

Although he passed away on January 30, 2001, at the age of 92, the last male survivor of the Titanic disaster, Michel always said, “I died at 4. Since then I have been a fare-dodger of life. A gleaner of time.”

One of the most forthright and determined of the real Titanic voices belonged to Edith Russell, the then 32-year-old first-class passenger who had managed to get aboard one of the lifeboats, still clutching a possession she regarded as her lucky talisman—a toy musical pig that played the pop tune “La Maxixe.”

Edith, a fashion buyer, journalist and stylist, had contacted producer Charles Brackett when she had first learned that the Barbara Stanwyck film was going to be made, outlining her experiences and offering her services. The letter elicited no response, as Brackett had decided not to speak to any individual survivors. The filmmakers were more interested in constructing their own story, one that would meet all the criteria of melodrama without getting bogged down by the real-life experiences of people like Edith.

The production team did, however, invite her—and a number of other survivors—to a preview of Titanic in New York in April 1953. It was an emotional experience for many of them, not least third-class passengers Leah Aks, who had been 18 at the time of the disaster, and her son, Philip, who had been only 10 months old. Edith recalled how, in the panic, the baby Philip had been torn out of his mother’s arms and thrown into her lifeboat. Leah tried to push her way into this vessel, but was directed into the next lifeboat to leave the ship. Edith had done her best to comfort the baby during that long, cold night in the middle of the Atlantic—repeatedly playing the tune of “La Maxixe” by twisting the tail of her toy pig—before they were rescued.

The reunion brought all these memories back. “The baby, amongst other babies, for whom I played my little pig music box to the tune of ‘Maxixe’ was there,” said Edith of the screening. “He [Philip] is forty-one years old, is a rich steel magnate from Norfolk, Virginia.”

Edith enjoyed the event, she said, and had the opportunity of showing off the little musical pig, together with the dress she had worn on the night of the disaster. Edith congratulated Brackett on the film, yet, as a survivor, she said she had noticed some obvious errors. “There was a rather glaring inadequacy letting people take seats in the lifeboat as most of them had to get up on the rail and jump into the boat which swung clear of the side of the boat,” she said. “The boat also went down with the most awful rapidity. It fairly shot into the water whereas yours gracefully slid into the water.” Despite these points, she thought the film was “splendid”—she conceded he had done a “good job”—and, above all, it brought the night alive once more. “It gave me a heartache and I could still see the sailors changing the watches, crunching over the ice and going down to stoke those engines from where they never returned,” she said.

After the melodrama of the Titanic film—the movie won an Academy Award in 1953 for its screenplay—the public wanted to know more about the doomed liner. The demand was satisfied by Walter Lord, a bespectacled advertising copywriter who worked for J. Walter Thompson in New York. As a boy, Lord, the son of a Baltimore lawyer, had sailed on the Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic. With an almost military precision—Lord had worked as both a code clerk in Washington and as an intelligence analyst in London during World War II—he amassed a mountain of material about the ship, and, most important, managed to locate, and interview, more than 60 survivors. The resulting book, A Night to Remember, is a masterpiece of restraint and concision, a work of narrative nonfiction that captures the full drama of the sinking. On its publication in the winter of 1955, the book was an immediate success—entering the New York Times best-seller list at Number 12 in the week of December 11—and since then has never been out of print. “In the creation of the Titanic myth there were two defining moments,” wrote one commentator, “1912, of course, and 1955.”

The publication of A Night to Remember—together with its serialization in the magazine Ladies’ Home Journal in November 1955—had an immediate effect on the remaining survivors, almost as if the Titanic had been raised from the murky depths of their collective consciousness.

Madeleine Mellenger wrote to Lord himself, telling him of her emotions when the Carpathia pulled into New York. “The noise, commotion and searchlights terrified me,” she said. “I stood on the deck directly under the rigging on which Captain Arthur Rostron climbed to yell orders thru’ a megaphone....I live it all over again and shall walk around in a daze for a few days.” Memories of the experience came back in flashes—the generosity of an American couple, honeymooners on board the Carpathia, who gave her mother, who was shoeless, a pair of beautiful French bedroom slippers, which were knitted and topped with big pink satin bows; and the horror of being forced to spend what seemed like an eternity in a cabin with a woman, Jane Laver Herman, who had lost her husband in the sinking.

Walter Lord became a receptacle into which survivors could spill their memories and fears. He, in turn, collected survivors’ tales, and memorabilia such as buttons, menus, tickets and silver spoons, with a near-obsessive passion, hoarding information about the Titanic’s passengers long after he had sent his book off to the publishers.

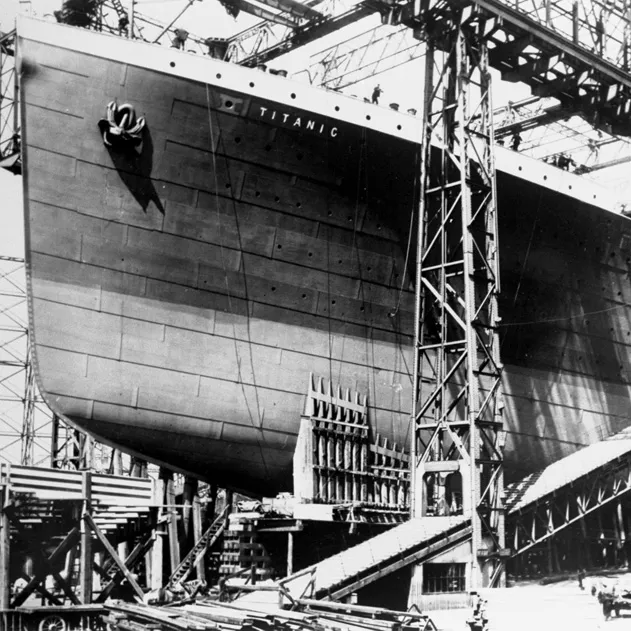

There was a rush to transfer Lord’s book to the screen, first in an American TV drama made by Kraft Television Theatre, which had an audience of 28 million when it aired in March 1956, and then in a big-budget British movie, which would be released in 1958. The rights to the book were bought by William MacQuitty, an Irish-born producer who, like Walter Lord, had been fascinated by the Titanic since he was a boy. As a child, growing up in Belfast, he remembered teams of 20 draft horses pulling the liner’s enormous anchors through the cobbled streets of the city, from the foundry to the Harland and Wolff shipyard.

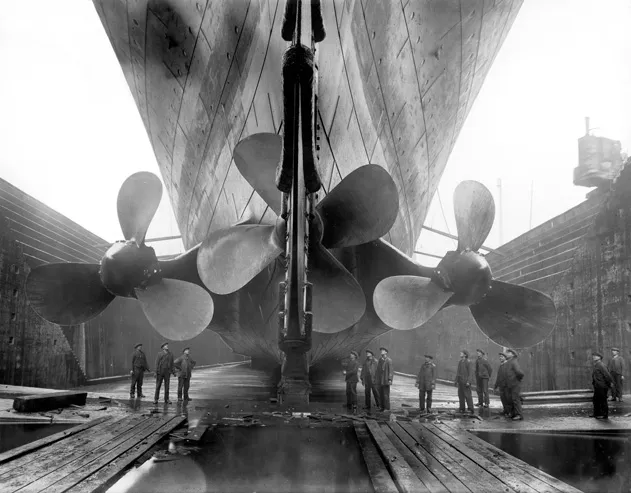

MacQuitty chose Roy Baker as director, Eric Ambler as scriptwriter and Walter Lord as a consultant on the project. The overall effect MacQuitty wanted to achieve was one of near-documentary realism. Art director Alex Vetchinsky employed his obsessive eye for detail to recreate the Titanic itself. Working from original blueprints of the ship, Vetchinsky built the center third of the liner, including two funnels and four lifeboats, an undertaking that required 4,000 tons of steel. This was constructed above a concrete platform, which had to be strong enough to support the “ship” and the surging mass of hundreds of passengers who were shown clinging to the rails to the very last.

Survivor Edith Russell still felt possessive of the Titanic story—she believed it was hers alone to tell—and she wanted to exploit it for all it was worth. She and Lord met in March 1957 at a lunch given by MacQuitty at a Hungarian restaurant in London. The gentleman writer and the grand lady of fashion hit it off immediately, drawn together by a shared passion for the Titanic and a sense of nostalgia, a longing for an era that had died somewhere between the sinking of the majestic liner and the beginning of World War I. Driven by an equally obsessive interest in the subject, Lord fueled Edith’s compulsion, and over the course of the next few years he sent her a regular supply of information, articles and gossip regarding the ship and its passengers.

Edith made regular visits to Pinewood, the film studio near London, to check on the production’s progress. Even though Edith was not employed on the project, MacQuitty was wise enough to realize there was little point in making an enemy of her.

As Edith aged, she became even more eccentric. When she died, on April 4, 1975, she was 96 years old. The woman who defined herself by the very fact that she had escaped the Titanic left behind a substantial inheritance and a slew of Titanic stories. To Walter Lord she pledged her famous musical pig. When Lord died in May 2002, he in turn left it to the National Maritime Museum, which also holds Edith’s unpublished manuscript, “A Pig and a Prayer Saved Me from the Titanic.”

In the years after A Night to Remember, the storm that had gathered around the Titanic seemed to abate, despite the best efforts of the Titanic Enthusiasts of America, the organization formed in 1963 with the purpose of “investigating and perpetuating the history and memory of the White Star liners, Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic.” The group, which later renamed itself the Titanic Historical Society, produced a quarterly newsletter, the Titanic Commutator, which over the years was transformed into a glossy journal. Yet, at this time, the membership comprised a relatively small group of specialists, maritime history buffs and a clutch of survivors. By September 1973, when the group held its tenth anniversary meeting, the society had a membership of only 250. The celebration, held in Greenwich, Connecticut, was attended by 88-year-old Edwina Mackenzie, who had sailed on the Titanic as 27-year-old second-class passenger Edwina Troutt. After more than 60 years she still remembered seeing the liner sink, “one row of lighted portholes after another, gently like a lady,” she said.

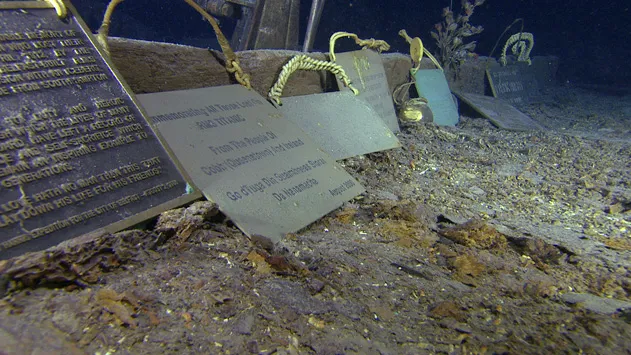

Many people assumed that, after 50 years, the liner, and the myths surrounding it, would finally be allowed to rest in peace. But in the early hours of September 1, 1985, oceanographer and underwater archaeologist Robert Ballard from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution—together with French explorer Jean-Louis Michel from the French organization Ifremer—discovered the wreck of the Titanic lying at a depth of roughly two and half miles, and around 370 miles southeast of Mistaken Point, Newfoundland. “The Titanic lies now in 13,000 feet of water on a gently sloping Alpine-looking countryside overlooking a small canyon below,” said Ballard, on returning to America a number of days later. “Its bow faces north. The ship sits upright on its bottom with its mighty stacks pointed upward. There is no light at this great depth and little life can be found. It is a quiet and peaceful place—and a fitting place for the remains of this greatest of sea tragedies to rest. Forever may it remain that way. And may God bless these now-found souls.”

The world went Titanic-crazy once more, a frenzy that was even more intense than the previous bouts of fever. There was something almost supernatural about the resulting pictures and films, as if a photographer had managed to capture images of a ghost for the first time.

Within a couple of years of Ballard’s discovery, wealthy tourists could pay thousands of dollars to descend to the site of the wreck and see the Titanic for themselves, an experience that many likened to stepping into another world. Journalist William F. Buckley Jr. was one of the first observers outside the French and American exploratory teams to witness the ship at close quarters. “We descend slowly to what looks like a yellow-white sandy beach, sprinkled with black rocklike objects,” he wrote in the New York Times. “These, it transpires, are pieces of coal. There must be 100,000 of them in the area we survey, between the bow of the ship and the stern, a half-mile back. On my left is a man’s outdoor shoe. Left shoe. Made, I would say, of suede of some sort. I cannot quite tell whether it is laced up. And then, just off to the right a few feet, a snow-white teacup. Just sitting there...on the sand. I liken the sheer neatness of the tableau to a display that might have been prepared for a painting by Salvador Dali.”

Over the course of the next few years, around 6,000 artifacts were recovered from the wreck, sent to a specialist laboratory in France and subsequently exhibited. The shows—the first of which was held at the National Maritime Museum in London in 1994— proved to be enormous crowd-pleasers. Touring exhibitions such as “Titanic Honour and Glory” and “Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition” have been seen by millions of people all around the world. Items on display include a silver pocket watch, its hands stopped at 2:28 a.m., the time the Titanic was sinking into the ice-cold waters of the Atlantic; the Steiff teddy bear belonging to senior engineer William Moyes, who went down with the ship; the perfume vials belonging to Adolphe Saalfeld, a Manchester perfumer, who survived the disaster and who would have been astonished to learn that it was still possible to smell the scent of orange blossom and lavender nearly 100 years later. There were cut-crystal decanters etched with the swallowtail flag of the White Star Line; the white jacket of Athol Broome, a 30-year-old steward who did not survive; children’s marbles scooped up from the seafloor; brass buttons bearing the White Star insignia; a selection of silver serving plates and gratin dishes; a pair of spectacles; and a gentleman’s shaving kit. These objects of everyday life brought the great ship—and its passengers—back to life as never before.

Millvina Dean first became a Titanic celebrity at the age of 3 months when she, together with her mother, Georgette Eva, and her brother, Bertram, known as Vere, traveled back after the disaster to England on board the Adriatic. Passengers were so curious to see, hold and have their photographs taken with the baby girl that stewards had to impose a queuing system. “She was the pet of the liner during the voyage,” reported the Daily Mirror at the time, “and so keen was the rivalry between women to nurse this lovable mite of humanity that one of the officers decreed that first- and second-class passengers might hold her in turn for no more than ten minutes.”

After returning to Britain, Millvina grew up to lead what, at first sight, seems to be an uneventful life. Then, Ballard made his discovery. “Nobody knew about me and the Titanic, to be honest, nobody took any interest, so I took no interest either,” she said. “But then they found the wreck, and after they found the wreck, they found me.”

This was followed in 1997 by the release of James Cameron’s blockbuster film, Titanic, starring Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio as two lovers from vastly different backgrounds who meet on board the doomed ship. Suddenly, in old age, Millvina was famous once more. “The telephone rang all day long,” she told me. “I think I spoke to every radio station in England. Everybody wanted interviews. Then I wished I had never been on the Titanic, it became too much at times.”

Of course, Millvina had no memories of the disaster—she was only 9 weeks old at the time—but this did not seem to bother either her legion of fans or the mass media. As the last living survivor of the Titanic Millvina Dean became an emblem for every survivor. She stood as a symbol of courage, dignity, strength and endurance in the face of adversity. The public projected on to her a range of emotions and fantasies. In their eyes, she became part Millvina Dean and part Rose DeWitt Bukater, the fictional heroine in Cameron’s film, who, in old age, is played by the elderly Gloria Stuart. “Are you ready to go back to Titanic?” asks modern-day treasure hunter Brock Lovett, played by Bill Paxton. “Will you share it with us?” Rose stands in front of one of the monitors on board Lovett’s ship, her hand reaching out to touch the grainy images of the wreck sent up from the bottom of the ocean. For a moment it all seems too much for her as she breaks down in tears, but she is determined to carry on. “It’s been 84 years and I can still smell the fresh paint,” she says. “The china had never been used, the sheets had never been slept in. Titanic was called the ship of dreams and it was, it really was.”

In the same way, Millvina was often asked to repeat her story of that night, but her account was secondhand, most of it pieced together from what her mother had told her, along with fragments from newspapers and magazines.

“All I really know is that my parents were on the ship,” she told me. “We were emigrating to Wichita, Kansas, where my father wanted to open a tobacconist’s shop—and one night we were in bed. My father heard a crash and he went up to see what it was about. He came back and said, ‘Get the children out of bed and on deck as quickly as possible.’ I think that saved our lives because we were in third class and so many people thought the ship to be unsinkable. I was put in a sack because I was too small to hold and rescued by the Carpathia, which took us back to New York. We stayed there for a few weeks, before traveling back to Britain. My mother never talked about it, and I didn’t know anything about the Titanic until I was 8 years old and she married again. But from then on, the Titanic was, for the most part, never mentioned.”

The Titanic came to represent a ship of dreams for Millvina, a vessel that would take her on a surreal journey. She transformed herself not only into a celebrity but also, as she freely admitted, into a piece of “living history.” “For many people I somehow represent the Titanic,” she said.

After a short illness, Millvina died on May 31, 2009; at 97, she had been the last survivor of the Titanic.

A few weeks after the Titanic disaster, Thomas Hardy wrote “The Convergence of the Twain,” his famous poem about the conjunction between the sublime iceberg and the majestic liner. First published in Fortnightly Review in June 1912, it articulates the “intimate wedding” between a natural phenomenon and a symbol of the machine age. The marriage of the “shape of ice” and the “smart ship” is described as a “consummation,” a grotesque union that “jars two hemispheres.” One hundred years after the sinking we are still feeling the aftershocks of the wreck as the “twin halves” of this “august event” continue to fascinate and disturb us in equal measure.

Indeed, the disaster has become so invested with mythical status—it’s been said that the name Titanic is the third most widely recognized word in the world, after “God” and “Coca-Cola”—that it almost seems to be a constant, an event that repeats itself on a never-ending loop.

Andrew Wilson, based in London, drew on unpublished sources and archival research for his new book on the Titanic saga.

Copyright © 2012 by Andrew Wilson. From the forthcoming book Shadow of the Titanic by Andrew Wilson to be published by Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.