Trove of African Modernist Masterpieces Spent Decades Hidden in Rural Scotland

A two-year research project identified 12 overlooked paintings, drawings and prints by pioneering 20th-century artists

:focal(411x232:412x233)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/7d/db7dcf7d-9283-403a-bd34-45fa5a1977fd/st_as.png)

Researchers at the University of St. Andrews in eastern Scotland have attributed long-overlooked works from a local art collection to some of Africa’s most renowned 20th-century painters.

As Jody Harrison reports for the Scottish Herald, the scholars’ research enabled them to confidently attribute ten drawings and paintings in the Argyll and Bute Council’s art collection to such prominent artists as Samuel Ntiro of Tanzania and Jak Katarikawe of Uganda. When the two-year venture began, the team had only been able to positively identify the author of one of these works, notes the research project’s website.

“It has been remarkable to uncover their histories,” says art historian Kate Cowcher in a statement. “To have the opportunity to bring these artworks together and share their stories with those living in the area, as well as further afield, is a privilege.”

Cowcher embarked on the project after making a chance discovery while conducting research for a lecture. When she learned that a canvas by Ntiro was housed in a collection in the Scottish countryside, she reached out to a local council, which helped her track the works to a high school in Lochgilphead, writes Kabir Jhala for the Art Newspaper. Many of the 173 paintings, prints, sculptures and ceramics were created by Scottish artists, but at least 12 originated in Africa.

Scottish novelist and poet Naomi Mitchison amassed the art during the 1960s and ’70s, when she was a frequent visitor to East and South Africa.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/b0/25b06c61-7e2f-4a86-a478-1639427d801a/dr-cowcher-and-assistants.jpeg)

Per the Argyll Collection’s website, Mitchison hoped to use the collection to underscore similarities between Scotland and newly decolonized African nations: Both experienced extreme social upheaval, the former when liberating their people from centuries of colonial rule, and the latter during the Highland Clearances of 1750 to 1860. (A period of drastic depopulation, the clearances found wealthy landowners forcibly evicting thousands of Scottish Highlanders to clear the way for large-scale sheep farms.)

Mitchison visited art galleries and art schools in Kampala, Nairobi, Lusaka, Dar es Salaam and other locales. She had a limited budget, spending no more than £100 (about $2,765 when adjusted for inflation) on each purchase, but exhibited a keen creative eye, often buying directly from undergraduate students who went on to become well-known artists.

“She collected Modernist African art at a time when it wasn’t seen as exciting,” Cowcher tells the Art Newspaper. “Most people on their travels to the region brought back traditional textiles and artifacts, not art.”

Mitchison collaborated with Jim Tyre, the local council’s art advisor, to establish the Argyll Collection as a teaching tool for rural schoolchildren. Following Tyre’s retirement in 1988, however, a lack of funding and resources left the trove largely overlooked, per the collection’s website.

Thanks to the researchers’ efforts, all of the Argyll Collection’s holdings have now been catalogued and properly attributed. A key highlight of the trove is Ntiro’s Cutting Wood (circa 1967), a landscape scene that depicts half-cut trees and plants in a Tanzanian village. Like Ntiro’s other works, the painting reflects rural life in a flattened, stylized manner.

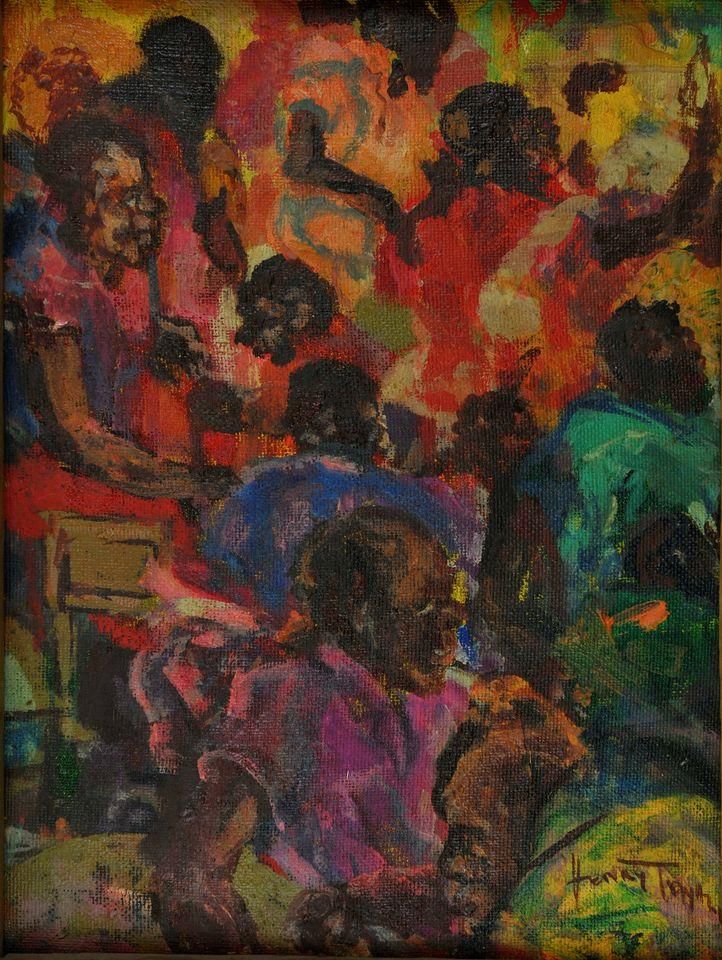

Another important piece in the collection is Untitled (circa 1971) by Zambian artist Henry Tayali. Painted in shades of red, purple and green, the artwork shows a group of people packed into a crowded room. As scholar Zenzele Chulu notes in the catalogue entry for the painting, the quotidian scene exemplifies Tayali’s “philosophy of revealing the day-to-day suffering of ordinary people.”

Overall, the Argyll Collection’s website states, the artworks showcase the “rich diversity of modern art practice amongst young African artists; they challenge stereotypical images of the continent, require individual engagement and encourage a sense of affiliation between geographically far-removed places.”

Twelve of the newly reattributed works are set to go on view at Dunoon Burgh Hall next month, reports Lauren Taylor for the Press and Journal. The exhibition, titled “Dar to Dunoon: Modern African Art From the Argyll Collection,” will trace the paintings’ journey from Africa to rural Scotland, in addition to offering an array of biographical information and archival finds.

“There is going to be a balancing act with this exhibition,” Cowcher tells the Art Newspaper. “There will be mention of the post-colonial context and the dynamics of Western collecting in the region. But equally what I want viewers to take away is the sense of energy and excitement that existed around African independence, as well as the wide-ranging Modernist art practice that developed there.”

“Dar to Dunoon: Modern African Art From the Argyll Collection” will be on view at Dunoon Burgh Hall in Dunoon, Scotland, between May 21 and June 13.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)