Vivian Maier: The Unheralded Street Photographer

A chance find has rescued the work of the camera-toting baby sitter, and gallery owners are taking notice

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Indelible-Carole-Pohn-children-631.jpg)

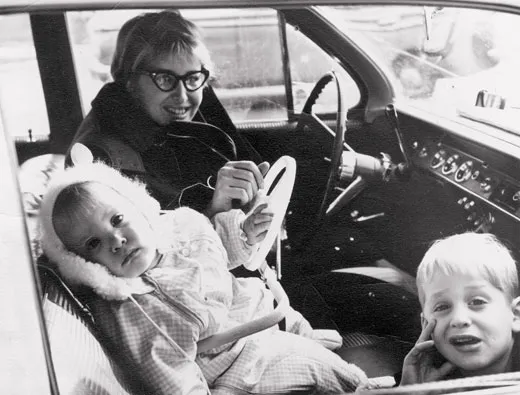

Brian Levant’s mother, brother and sister were waiting to give him a ride home from the skating rink one day in the early 1960s when the neighbors’ nanny appeared. “I was coming toward the car,” Levant recalls, “and she just stuck the lens in there in the window and took a picture.” Residents of the Chicago suburb of Highland Park had gotten used to the nanny doing that, along with her French accent, her penchant for wearing men’s coats and boots, and the look and gait that led children to call her “bird lady.”

Her real name was Vivian Maier, and she wore a Rolleiflex twin-lens reflex camera around her neck, more body part than accessory. She’d snap pictures of anything or anyone as she lugged her charges on field trips into Chicago, photographing the elderly, the homeless, the lost. But her photograph of Carole Pohn and her children Andy and Jennifer Levant, from 1962 or ’63, is one of the very few prints Maier ever shared; she gave it to Pohn, a painter, telling her she was “the only civilized person in Highland Park.” Pohn says she tacked the print up on a bulletin board “with a million other things”—an act that embarrasses her today. After all, she says, Maier is “a photographer of consequence now.”

Yes she is. Maier’s recent, sudden ascent from reclusive eccentric to esteemed photographer is one of the more remarkable stories in American photography. Though some of the children she helped raise supported Maier after they came of age, she couldn’t make the payments on a storage locker she rented. In 2007, the locker’s contents ended up at a Chicago auction house, where a young real estate agent named John Maloof came upon her negatives. Maloof, an amateur historian, spotted a few shots of Chicago he liked. He bought a box of 30,000 negatives for $400.

Maloof knew the locker had belonged to someone named Vivian Maier but had no idea who she was. He was still sifting through the negatives in April of 2009 when he found an envelope with her name penciled on it. He Googled it and found a paid death notice that had appeared in the Chicago Tribune just a few days before. It began: “Vivian Maier, proud native of France and Chicago resident for the last 50 years, died peacefully on Monday.” In fact, Maloof would later learn, Maier had been born in New York City in 1926, to a French mother and Austrian father; she had spent part of her youth in France, but she worked as a nanny in the United States for half a century, winding down her career in the 1990s. In late 2008, she slipped on a patch of ice, sustaining a head injury that spiraled into other health problems. She died April 20, 2009, age 83.

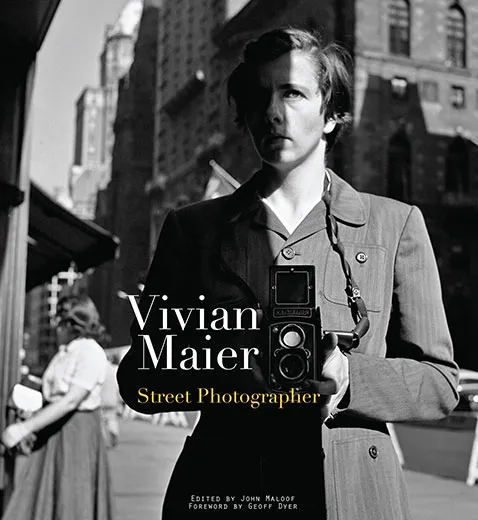

Maloof started a blog and began posting Maier’s photographs on Flickr. Soon, people who knew more than he did about photography were telling him he had something special on his hands. News reports followed, then interest from galleries. There now have been, or soon will be, Vivian Maier shows in Chicago, New York and Los Angeles, as well as Germany, Norway, England and Denmark. Maloof has edited a book of her work, Vivian Maier: Street Photographer, which was published in November, and has raised money for a documentary film about her that is in the works.

Maloof has now accumulated at least 100,000 Maier negatives, buying them from other people who had acquired them at the 2007 auction; a collector named Jeffrey Goldstein owns an additional 15,000. Both men are archiving their collections, posting favorite works online as they progress, building a case for Vivian Maier as a street photographer in the same league as Robert Frank—though Goldstein acknowledges that gallery owners, collectors and scholars will be the ultimate arbiters.

Current professional opinion is mixed. Steven Kasher, a New York gallerist planning a Maier exhibition this winter, says she has the skill “of an inborn melodist.” John Bennette, who curated a Maier exhibition on view at the Hearst Gallery in New York City, is more guarded. “She could be the new discovery,” he says, but “there’s no one iconic image at the moment.” Howard Greenberg, who will show her work at his New York gallery from December 15 through January 28, says, “I’m taken by the idea of a woman who as a photographer was completely in self-imposed exile from the photography world. Yet she made thousands and thousands of photographs obsessively, and created a very interesting body of work.”

What made Vivian Maier take so many pictures? People remember her as stern, serious and eccentric, with few friends, and yet a tender, quirky humanity illuminates the work: old folks napping on a train; the wind ruffling a plump woman’s skirt; a child’s hand on a rain-streaked window. “It seems to me there was something disjointed with Vivian Maier and the world around her,” Goldstein says. “Shooting almost tethered her to people and places.”

Now, her work tethers others to those people and those places. “How close did this come to just being tossed in some bin, recycled, you know?” says Brian Levant, who eagerly checks Goldstein’s and Maloof’s blogs. “Instead you have half a century of American life.”

David Zax, a freelance writer living in Brooklyn, is a frequent contributor to Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)