Final Mission: Staging Japan’s Surrender

General Douglas MacArthur was a war hero—and an old soldier who knew how to put on a show.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/94/6b94bc67-6357-4b94-87d3-bf236df571f7/07g_sep2020_surrenderceremoniesusac-4626_live.jpg)

Even though the war was over, General Douglas MacArthur was embroiled in one final complex campaign. Japan’s public surrender ceremony was a momentous occasion that required flawless execution. The whole world would be watching.

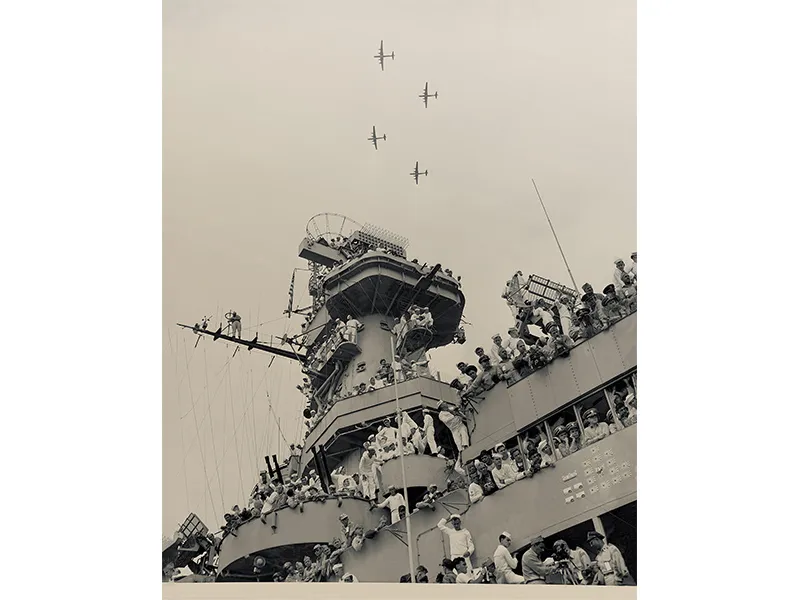

The September 2, 1945, ceremony aboard the 45,000-ton battleship USS Missouri was a logistical nightmare for MacArthur’s staff and the ship’s crew. Men scrubbed the warship white-glove spotless. Hard-boiled combat leaders played the role of exasperated headmasters, fretting over the appearance, placement, and proper behavior of thousands of marines and sailors scheduled to be in attendance. The operation involved hundreds of documents, dignitaries, and delegates, not to mention the precise coordination of four U.S. destroyers deployed as water taxis for shuttling VIPs to the Missouri. On top of that, America’s fighting forces had to attend to the needs of 225 news correspondents and 75 photographers.

A mahogany table, provided by the British, was clearly too small for the leather and gold portfolios holding the surrender documents. Sailors improvised by quickly unbolting a larger substitute from the deck of a mess hall and covering it with a not-so-clean green tablecloth.

One of the Japanese representatives, Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, had a wooden leg. Worried that his slow gait might interfere with the occasion’s precise timing, officers ordered a sailor to limp the approach with a sawed-off broom handle in order to simulate Shigemitsu’s ponderous strides to the veranda deck. Planners stood by, stopwatches in hand. And then there was the business with a flag. Japan’s surrender would take place in Tokyo Bay but miles south of the city of Tokyo. The Missouri’s location was chosen because at that very spot in 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry had come ashore for the first time, when he had forced Japan to sign a treaty opening ports to U.S. merchant ships. MacArthur had Perry’s flag flown in from the collection of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The 31-star ensign, under glass, was mounted backward to be properly displayed on the Missouri’s starboard side bulkhead.

Next to MacArthur’s sprawling pageant, a royal wedding would have looked like a middle-school play.

By contrast, Germany’s surrender to Allied forces nearly four months before had taken place in a small dimly lit French schoolhouse, in the middle of the night. General Dwight D. Eisenhower expressly discouraged a “Hollywood show.” He didn’t even attend.

In the name of honor, dignity, and circumstance, MacArthur was doing things differently. For the Allied top brass, this sacred rite was the culmination of the greatest conflict the world had ever known. It was a day destined to appear in every history book for centuries. Meanwhile, the Missouri’s war-weary sailors looked upon the event as an unnecessary ego-fest staged by starched generals and admirals.

One thing they could all agree on was that the United States was the new big kid on this block. MacArthur barged into Tokyo Bay with an armada of 258 combat ships, vessels that helped shrink the Japanese sphere of influence back to the shores of the home islands. The overwhelming superiority of American forces would be on full display.

The general was an avid student of military history. He concocted a particularly powerful scene for the final act of World War II. Centuries before, the ancient Romans developed the custom of forcing their defeated enemies to “pass under the yoke.” Prisoners were led, hands tied, under a wooden crosspiece used to subjugate a pair of oxen. The act symbolized the transition of the routed army from warriors to slaves. Often, the yoke was replaced with something more readily available—an allegorical archway hastily built from Roman spears.

MacArthur planned to subject the Japanese delegation to an updated version of this centuries-old practice. In place of spears, the general would exhibit the weapons that had turned Japan’s cities to ashes. At the moment MacArthur signed the surrender documents—planners had it pegged at exactly 9:08 a.m.—he wanted the skies over the battleship to blacken with squadrons of American warplanes.

Months before, American combat aircraft were lugging bombs into Japanese airspace almost every day. After hostilities ended, they kept coming, now laden with food and supplies. On September 2, MacArthur wanted as many airplanes as possible, a demonstration of overwhelming force that would be an admonition designed to quell any slight hope of resistance. It also served as a warning to all other nations that the United States was now the world’s sole nuclear superpower.

Aircraft would come from both U.S. Army and Navy units. The latter would be much easier. With the exception of the USS Cowpens, America’s Task Force 38 carriers were not in Tokyo Bay, but they were still sailing close by. They had been roaming the eastern coastline of Japan for months, launching unforgiving attacks. When the fighting ceased, the naval airplanes flew reconnaissance missions over scorched cities, conducted patrols, and helped locate and deliver supplies to POW camps.

For the Army, the long haul to Tokyo Bay was a tougher task. The aircraft that MacArthur most wanted to show off were America’s squadrons of B-29 heavy bombers. These were the aircraft that had been pivotal in the devastation of Japanese cities and that had delivered the atomic bombs that ended the war. It was also not lost on the general that the sight of hundreds of long-range Superfortress aircraft, streaming overhead in a seemingly endless procession, was bound to leave an impression on the members of the Soviet delegation standing below.

The five bomb wings operating B-29s from the Mariana Islands were based more than 1,500 miles away, and Superfortress crews knew that flying the bombers was often a dangerous undertaking. The average B-29 crewman was much more likely to die in an accident or a mechanical failure than from enemy action. Conducting long, over-water missions in wartime was one thing, many thought, but flying them for show was something else entirely. Men who had survived months of combat—undertaking white-knuckle takeoffs, avoiding Japanese flak and fighters, and perhaps sweating out an emergency landing or two—were dubious about making passes through what was shaping up to be the most crowded airspace on Earth. What if their number came up?

Captain Robert J. Willman, pilot of the B-29 City of Duluth based on Guam, wrote about the debate years later in a Veterans Memorial Hall piece. “Personally, I was against the idea because we had been lucky so far and things can happen on a 15-hour trip over 3,000 miles of ocean,” he recalled. “I asked each member of the crew about their feeling. Bill Grossmiller, our bombardier and youngest man, appeared excited about the trip. So Bill went with another crew.”

The Army Air Forces considered themselves technically at war up to the moment the surrender documents were signed, so some fliers elected to make the trip purely to get another combat mission under their belts. Others were drawn by their desire to see the destruction they had wrought on Tokyo; most of their missions had been flown at night, and they didn’t linger for damage assessment.

For someone at the level of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas R. Vaucher, the 462nd Bomb Group’s operations officer, the mission was not optional. He had led a B-29 raid to Yokohama months before and was now chosen to wrangle the massive group of heavy bombers for their final mass flight. Four of the five wings would participate in the “display of power” over the Missouri. The fifth wing was also headed to Japan, but its mission was a supply drop to POW camps.

Vaucher’s orders were simple, but in many ways the show of force was more complex than a bombing mission. The timing was critically important—hitting a mark 1,500 miles away at a precise moment. The commander of the 58th Bomb Wing’s final words to his mission leader were, “Vaucher, this is one target time you’d better not miss!” General Roger M. Ramey would be watching his bombers from the Missouri, far below.

Beyond the precision timing, it had been a while since the bombers had flown in parade formation, let alone for nearly every VIP in the hemisphere. The fact that hundreds of Navy airplanes would be motoring through simultaneously made everyone uneasy.

Takeoffs would begin in darkness, at 2:01 a.m. After the long flight, the roughly 465 B-29s would join up near Japan’s coastline, ready to fly in formation by 8:33 a.m., with the curtain lifting at 9:08. Creating a massive shell game, the bombers would fly in a huge clockwise box, making it appear to the viewers below that there were double or triple the number of B-29s in the air. They were expected to cruise the pattern until 11:30 a.m. or until they were down to less than 600 gallons of fuel.

On this momentous day, there were a few things not even MacArthur could plan for. The weather was bad. Navy reports judged the flying environment “average to undesirable.” The B-29s would be lost in the clouds at their planned altitudes of 8,000 to 14,000 feet. The Army made the decision to drop them down to 3,000 feet. The Navy split the difference, tensely planning to thread their 349 Hellcats, Corsairs, Helldivers, and Avengers through at 1,500 feet.

Many B-29s arrived early. Rather than loiter at their meeting points, several pilots elected to have a look around. Pile Driver, flown by Captain Sterling N. Pile, toured Tokyo. Crewman John G. Sapuder told The Buffalo News, “I’d asked Captain Pile to show me the places he’d bombed with the plane. He flew at a real low altitude, and for blocks, you’d go without seeing any buildings. Everything was burned out.” Without meaning to, the aircraft got too close to the Missouri and was sternly turned away by a fighter on air patrol.

Similarly, The City of Kankakee went sightseeing. Crewman John E. Ryan told the Daily Journal, “[We] went over Tokyo, which was extremely interesting because there just wasn’t anything there. It was an amazing sight. There were people riding bicycles on the streets, but we were so low that they were looking up at us and losing their balance….”

Captain Vivian Lock, who had completed 25 missions over Japan, couldn’t help himself. He too guided his plane toward the Missouri and the fighters failed to catch him as he thundered over the battleship at 300 feet. “I could see all of the sailors dressed up in their whites—long lines of them two or three ranks deep, a hundred or so in each line… I could see the table with the men seated and apparently signing something, but I couldn’t see who was doing the signing—American or Japanese,” recalled Ryan.

It is perhaps The City of Kankakee that can be heard on CBS reporter Webley Edwards’ radio broadcast, when about 14 minutes in he says, “And here comes one of the big B-29s, which I suppose is the leader of the flight which was to put on a demonstration of airpower over the bay this morning. The weather is miserable….”

The airplanes were late. At 9:25 a.m., the surrender documents had been signed and the Japanese were preparing to depart. MacArthur stated, “These proceedings are now closed.” Moments later, he grabbed Admiral Halsey’s shoulder and whispered, “Bill, where the hell are those airplanes?”

In his autobiography, Reminiscences, MacArthur described what happened next: “At that moment, the skies parted and the sun shone brightly through the layers of clouds. There was a steady drone above and now it became a deafening roar and an armada of airplanes paraded into sight, sweeping over the warships…. It was over.”

And, for the war-weary airplane crews, it was one flight closer to going home.