Sports History Forgot About Tidye Pickett and Louise Stokes, Two Black Olympians Who Never Got Their Shot

Thanks to the one-two punch of racism and sexism, these two women were shut out of the hero’s treatment given to other athletes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/0a/790a7b51-fe30-49c8-abcb-5e41d6f31150/gettyimages-517731020.jpg)

When United States Women’s Track & Field standouts Tori Bowie and Allyson Felix lowered themselves into the starting blocks on the track at Olympic Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, spectators in person and watching at home held their breath in the three-count between “set” and the crack of the starting pistol.

As the athletes' muscles flex and relax and arms pump in those few precious seconds until someone—hopefully a crowd favorite—crosses the finish line first.

When the race unfolds, with the stationary background the static evidence of these women’s speed, viewers marvel.

But these record-breakers chase the footsteps of the groundbreakers before them. These athletes crossed barriers of not just race, but gender too, and they shouldered the great weight of staring down a 100-meter straightaway, knowing that once the starting pistol fired, history would be made.

***

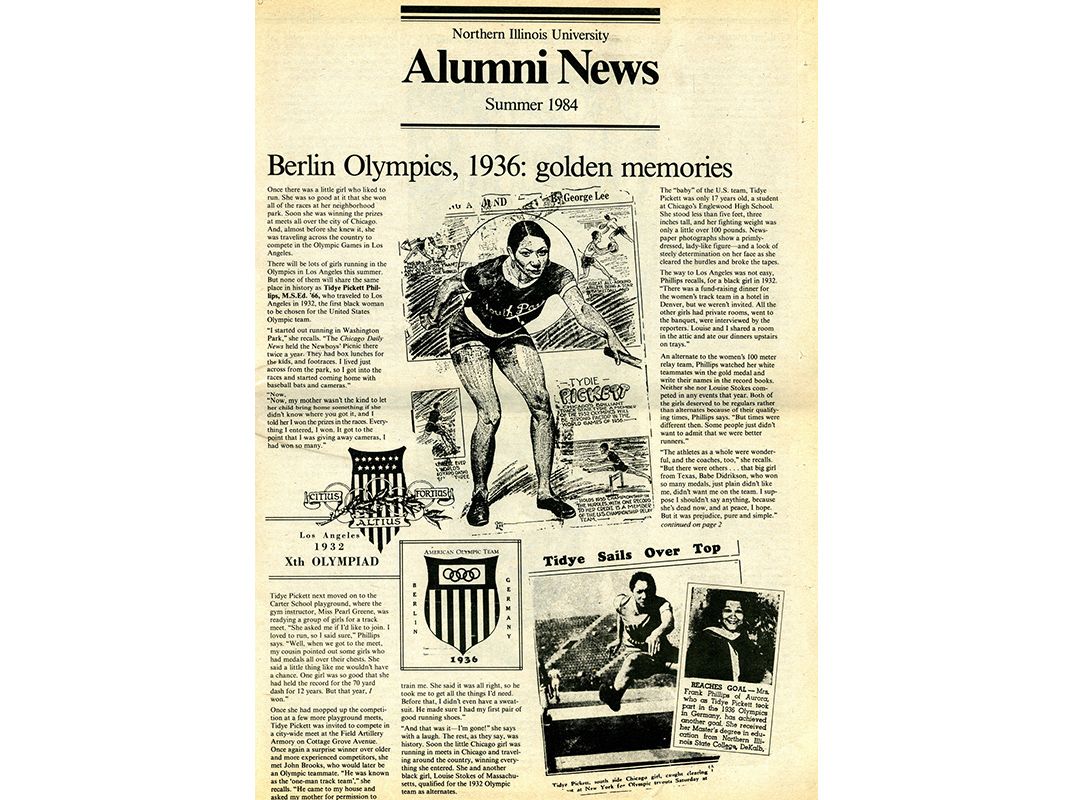

Tidye Pickett was born in 1914 and grew up in the Chicago neighborhood of Englewood. Long a center of African-American life in the Windy City, the area claims NBA stars Anthony Davis, Jabari Parker, and Derrick Rose as its own, as well as the minds of brilliant authors like Lorraine Hansberry and Gwendolyn Brooks.

When Picket was growing up, Englewood was a booming neighborhood filled with department stores, cafeterias, and home to Southtown Theater, at the time one of the largest theaters ever erected on Chicago’s South Side. The community had yet to experience the economic segregation wrought by redlining and other policies in the post-World War II era.

Pickett lived across the street from Washington Park, a place that often held races for boys and girls, races she won. Pickett was discovered by city officials who taught her how to run and jump, competing for the Chicago Park District track team.

Eventually, she would attract the attention of John Brooks, a University of Chicago athlete and one of the best long jumpers in the country who would go on to be a fellow Olympian. Seeing Pickett’s potential at a Chicago Armory event, he asked her parent’s permission to coach Pickett to the Olympics, which he did in 1932 and continued to do through the 1936 Games, where he finished 7th in the long jump.

Louise Stokes, meanwhile, grew up nearly 1,000 miles to the east in Malden, Massachusetts, where she excelled on the track at Malden High School. Born in 1913, Stokes was originally an athletic center on her middle school basketball team, but was encouraged by her teammates to take her speed to the track, where she became known as “The Malden Meteor.” She won title after title across New England.

As a member of the Onteora Track Club, she set a world record in the standing broad jump—an event long since forgotten, save for the National Football League scouting combine—at 8 feet, 5.75 inches. The United States Olympic Committee had no choice but to invite Stokes to the 1932 Olympic Trials in Evanston, Illinois, where she earned a spot on the Olympic team.

Including Pickett and Stokes in track and field events at the Olympics was controversial at the time, not just because of their race, but also because of their gender. The first time women were even allowed to compete in these events at the Olympics was in Amsterdam in 1928; they had previously only competed in less-strenuous activities including golf, tennis or archery.

“A lot of people thought it was damaging to [women’s] internal organs,” says Damion Thomas, the curator of sports at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. “[They believed it would] hinder their ability to be mothers. There were lot of ideas of women’s role in society and how we didn’t want sports to occupy their primary function.”

For Pickett and Stokes, the trials led to both women making the Olympic team as part of the 4x100 relay pool (the actual racers would be selected from this group at the Games themselves.) Stokes finished fourth in the 100-meter and Pickett finished sixth, which placed Stokes on the team and Pickett as an alternate.

In the lead up to the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, Pickett and Stokes were subjected to various abuses. They were kids: 17 and 18, respectively. In Denver, on the train en route to Los Angeles, they were given a separate room near a service area and ate their dinner in their rooms rather than the banquet hall with the rest of the delegation.

As the train continued west toward California, the two women were sleeping in the bunking compartment they shared, Stokes on the top bunk, Pickett on the bottom. One of the most well-known women in sport, Mildred “Babe” Didrikson tossed a pitcher of ice water on the sleeping teammates.

According to Thomas, Didrickson was opposed to having African-American athletes on the team, hence the slight. Pickett confronted Didrikson, the two exchanged words, but no one ever apologized.

In the book A to Z of American Women in Sports, author Paula Edelson reported that once in Los Angeles, “Stokes and Pickett practiced with their team during the day, but they were stranded each night in their dorms as the other runners gathered to eat in the whites-only dining room.”

The harshest rebuke came when the duo were replaced in the 4x100-meter relay by two white athletes, both of whom performed slower than Stokes and Pickett at the trials. The duo watched from the grandstand as the all-white relay team captured the gold, robbing them of their shot at glory. There was likely resentment, but as black women, they had no recourse or outlet to voice their anger. Pickett went to her grave believing that “prejudice, not slowness” kept her out of competition, according to her Chicago Tribune obituary.

“Lily-whiteism,” wrote Rus Cowan in the Chicago Defender at the time, “a thing more pronounced than anything else around here on the eve of the Olympic Games, threatened to oust Tidye Pickett and Louise Stokes from participation and put in their stead two girls who did not qualify.”

“I felt bad but I tried not to show it,” Stokes would say later. “I’ve kept it out of my mind.”

This snub, and their subsequent omission from the medal books, are among the many reasons why Pickett and Stokes are largely forgotten in the story of African-American sports groundbreakers.

A factor that may keep Pickett and Stokes from the collective Olympic memory, according to Thomas, is that they didn’t have the pedigree of being a product of the likes of Tuskegee University or Tennessee State University, two predominant African-American track programs, Then there’s also the fact that they didn’t win any medals, though that clearly was through no fault of their own. Other reasons include an imbalance in scholarship of the lives of black female athletes and convoluted Cold War gamesmanship in which official records were skewed (and women’s feats deemphasized) to “prove” America’s athletic prowess over the Soviet Union.

Whether Pickett and Stokes had personal reservations about returning to the Olympics in 1936, this time in Berlin, is unknown, but both made the transatlantic journey. Stokes’ hometown raised the $680 to send her there.

Stokes had a poor Olympic trials in 1936, but was invited to join the pool of athletes anyway again as a candidate to run on the 400-meter relay team. When she boarded the boat to Berlin, according to the Defender, “There was no happier athlete on the boat.” Once in Berlin, her experience was mostly the same as she sat in the stands and watched her fellow Americans, but with one exception. This time, her teammate Tidye Pickett would be on the track.

Pickett had recently run the opening leg of a Chicago Park District 400-meter relay team, setting an unofficial world record in 48.6 seconds. At the trials, Pickett finished second in the 80-meter hurdles, which gave her an automatic qualification for the event in Berlin.

Then 21, Pickett’s became the first African-American woman to compete in the Olympic Games, reaching the semi-finals of the 80-meter hurdles. In that race, she hit the second hurdle and broke her foot and didn’t finish the race.

Even if Stokes and Pickett were open to competing in another Olympics, the cancellation of the 1940 and 1944 Games due to World War II made such an endeavor impossible. It wouldn’t be until the 1948 Olympics, when Alice Coachman won gold in the high jump, that an African-American woman would take home a medal. Pickett and Stokes would return to their lives in Illinois and Massachusetts, and both would return to the segregated life from which they temporarily departed.

Thomas ascribes this, however, less to race than to gender.

“The Olympics at the time were amateur sports,” he said. “There was no expectation they’d parlay their success into opportunities at home.”

Despite a second straight Olympics without participation, Stokes returned to her hometown in Malden to a hero’s parade. She remained active and started the Colored Women’s Bowling League, winning many titles, and she remained involved in local athletics until she died in 1978. She was honored by the Massachusetts Hall of Black Achievement and has a statue in the Malden High School courtyard.

Pickett went on to serve as a principal at an East Chicago Heights elementary school for 23 years. When she retired in 1980, the school was renamed in her honor. (The school closed its doors for good in 2006 due to poor performance.)

While Pickett and Stokes may be largely unknown to the casual Olympic fan, , they’ve proved that simple, forced inclusion, by virtue of their undeniable speed, is enough to initiate the swinging pendulum of progress.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)