The Rise of the Modern Sportswoman

Women have long fought against the assumption that they are weaker than men, and the battle isn’t over yet

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/46/d0461fa4-8d94-4a13-a456-6def4c2ae232/http_sirismmsiedu_npm_1985_0796_3151_1-4jpg_copy.jpg)

During the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, more women than ever before ran, jumped, swam, shot, flipped, hit and pedaled their way to glory. Of the more than 11,000 athletes who came to compete in Rio, 45 percent were women. Many of them—Serena Williams, Simone Biles and Katie Ledecky to name a few—have become household names. But 120 years ago, there might as well have been a “No Girls Allowed” sign painted on the entrance to the first modern Olympics, when 241 athletes, all men, from 14 countries gathered in Athens, Greece.

In the words of the founder of the Olympic movement, French aristocrat Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the Games were created for “the solemn and periodic exaltation of male athleticism” with “female applause as reward.” That women shouldn’t compete in the Games was self-explanatory, said Coubertin: “as no women participated in the Ancient Games, there obviously was to be no place for them in the modern ones.”

But that’s not exactly true—the ancient Greek women had their own Olympics-like contest. Rather, Coubertin’s belief that women had always been excluded played into the predominant theory that women (with “women” coded to mean well-to-do white women) were the weaker sex, unable to physically endure the strains of competitive sport.

One revealing statement by Coubertin best illustrates why he didn’t think women should participate:

“It is indecent that spectators should be exposed to the risk of seeing the body of a women being smashed before their eyes. Besides, no matter how toughened a sportswoman may be, her organism is not cut out to sustain certain shocks. Her nerves rule her muscles, nature wanted it that way.”

Just as women competed in ancient times, women were showing very real physical prowess during Coubertin’s day. During the inaugural Olympics, one or two women (historical accounts differ) even informally competed in the most physically grueling of all Olympic events: the marathon. But it would be a long time before society and science acknowledged that women belonged in the sporting world.

The Weaker Sex

The ideal Victorian woman was gentle, passive and frail—a figure, at least in part, inspired by bodies riddled with tuberculosis. These pale, wasting bodies became linked with feminine beauty. Exercise and sport worked in opposition to this ideal by causing muscles to grow and skin to tan.

“It's always been this criticism and this fear in women's sports [that] if you get too muscular, you're going to look like a man,” says Jaime Schultz, author of Qualifying Times: Points of Change in U.S. Women’s Sport.

To top off these concerns, female anatomy and reproduction baffled scientists of the day. A woman’s ovaries and uterus were believed to control her mental and physical health, according to historian Kathleen E. McCrone. “On the basis of no scientific evidence whatsoever, they related biology to behavior,” she writes in her book Playing the Game: Sport and the Physical Emancipation of English Women, 1870-1914. Women who behaved outside of society’s norm were kept in line and told, as McCrone writes, “physical effort, like running, jumping and climbing, might damage their reproductive organs and make them unattractive to men.”

Women were also thought to hold only a finite amount of vital energy. Activities including sports or higher education theoretically drained this energy from reproductive capabilities, says Schultz. Squandering your life force meant that “you couldn't have children or your offspring would be inferior because they couldn't get the energy they needed,” she says.

Of particular concern at the time was energy expenditure during menstruation. During the late 1800s, many experts cautioned against participating in any physical activity while bleeding. The “rest cure” was a common prescription, in which women surfed out the crimson wave from the confines of their beds—an unrealistic expectation for all but the most wealthy.

It was upper-class women, however, who helped push for women’s inclusion in Olympic competition, says Paula Welch, a sports history professor at the University of Florida. By participating in sports like tennis and golf at country clubs, they made these activities socially acceptable. And just four years after the launch of the modern Olympics, 22 women competed alongside men in sailing, croquet and equestrian competitions, and in the two women-only designated events, tennis and lawn golf. While the competition was small (and some didn’t even know they were competing in the Olympics), women had officially joined the competition.

Working-class women, meanwhile, pursued other means of getting exercise. Long-distance walking competitions, called Pedestrianism, was all the rage. The great bicycle fad of the 1890s showed women that they not only could be physically active, but also allowed them greater mobility, explains Schultz.

During this time, some medical researchers began to question the accepted ideas of what women were capable of. As a 28-year-old biology student at the University of Wisconsin, Clelia Duel Mosher started conducting the first-ever American study on female sexuality in 1892. She spent the next three decades surveying women's physiology in an effort to break down the assumptions that women were weaker than men. But her work proved an exception to the mainstream perspective, which stayed steadfastly mired in the Victorian era.

The Road to the Olympics

Born in 1884 in Nantes, France, Alice Milliat (her real name was Alice Joséphine Marie Million) believed women could achieve greater equality through sport. In 1921, frustrated by the lack of opportunities for women in the Olympics, she founded Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale (FSFI). The organization would launch the first Women’s Olympic Games, held in Paris in 1922. At these games, women competed in physically strenuous events like the 1000-meter race and shot put.

Millat’s success bred contemptment from the athletic establishment, namely the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the International Association of Athletic Federations (IAAF), who chafed at the independence under which these women flourished. In 1926, an agreement was struck such that the FSFI would agree to follow IAAF rules and drop its catchy name. In turn, the IOC added track-and-field events to the Amsterdam Games.

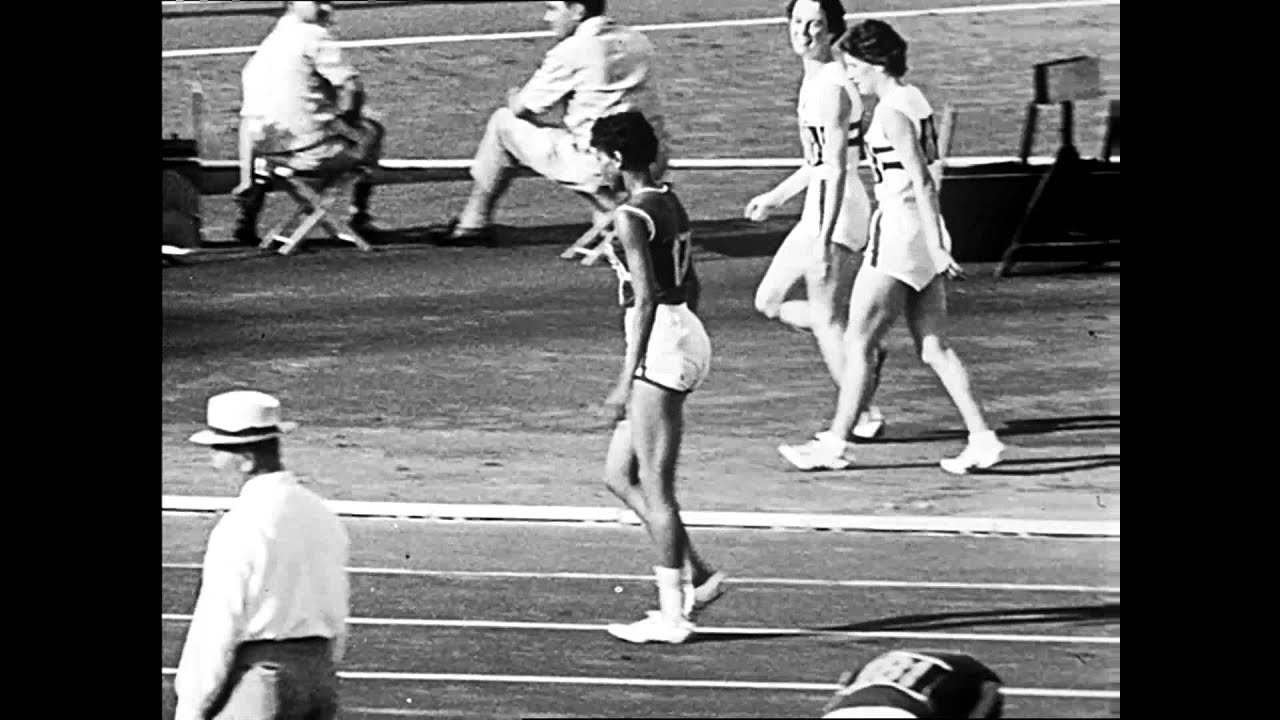

The 800-meter race—the longest distance women were given to run—would become a flashpoint that would resonate for decades. After the Olympic event, the female competitors appeared, (unsurprisingly) sweaty and out of breath. Even though the men didn’t look any better after their race, spectators were aghast. The distance was perceived as too much for the women. In the words of one sensational newspaper headline, the racers were “Eleven Wretched Women.” The backlash ensured that the distance would be banned from the Olympics until 1960.

The pushback came in part from physical educators, who were trained medical doctors yet believed that women could not handle undue physical strain. “When women were participating [in the physician’s tests] they generally didn’t train,” says Welch. “So when they did something that involved some endurance—after they ran 200 or 300 yards—they were rapidly breathing.” That spurred the idea that around 200 yards was the farthest distance a woman should run.

By 1920, despite these doubts, 22 percent of colleges and universities in the United States offered women’s athletic programs. But physical educators so deeply objected to women’s competitive sports that they successfully fought in the ’30s to replace competition at the collegiate level with game days and exercise classes. The mainstay Victorian belief that vigorous exercise was detrimental to childbearing echoed on.

On the Way to Equality

There were exceptions to the mainstream narrative. Women who swam, for instance, made early inroads. As no one could see them sweat, the sport didn’t look as strenuous. This likely was what allowed aquatics events for women to be introduced in the 1912 Olympic Games. But women had to work around gender norms of the day to train, Welch points out. As beaches required women wear stockings, members of the Women's Swimming Association would swim out to the jetties, where they’d take their stockings off and tie them to the rocks. At the end of their practice, the swimmers would return to the rocks, untie and put their stockings back on so they looked “presentable” when they resurfaced at shore.

“It was just something they had to deal with,” says Welch.

Shaking assumptions about what women were physically capable of took many forms in the early years of the Olympics. The swagger of early women athletes like Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias and Stanisława Walasiewicz “Stella Walsh” served as inspiration for others; both came away with gold hardware at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics.

But it was after the war, when the Soviet Union entered international sporting competitions, that the dogged, pervasive stereotypes of the Victorian era were finally forced out in the open. At the 1952 Helsinki Games, all Soviet athletes—men and women—arrived ready and trained to win. As the postwar Soviet Chairman of the Committee on Physical Culture and Sport, Nikolai Romanov, put it in his memoirs:

“… we were forced to guarantee victory, otherwise the ‘free’ bourgeois press would fling mud at the whole nation as well as our athletes … to gain permission to go to international tournaments I had to send a special note to Stalin guaranteeing the victory.”

The commanding presence of these Soviet women, whose wins counted just as much as the male athletes, left the United States little choice but to build up its own field of women contenders if it wanted to emerge victorious in the medal tally. By the 1960 Rome Games, the breakout performance of Wilma Rudolph, as well as those of her Tennessee State University colleagues, sent a clear message home, just as the women’s liberation movement was just taking seed.

As the number of women researchers and medical professionals grew, science began catching up with the expanding field of female athletes, says Karen Sutton, an orthopedic surgeon at Yale University and Head Team Physician for United States Women’s Lacrosse. And their research suggested that not only were women not the delicate waifs seen in popular culture, but that there were fewer physiologic barriers between men and women than previously thought.

“Whether or not there is a female response to exercise which is mediated solely by the factor of sex has not been determined,” wrote Barbara Drinkwater, a pioneer in the field, in her 1973 review on women’s physiologic response to exercise.

Though there appeared to be definite differences in the maximum capacities of men and women, several studies at the time documented that physical fitness could “override the effect of sex,” Drinkwater noted. One 1965 study found that oxygen uptake—a common measure of physical capacity—of female athletes could slightly exceed that of sedentary men.

Researchers during this time also began dispelling the widespread fears of combining exercise with menstruation. Long considered dirty or incapacitating in some cultures, menstruation has “historically been the focus of myth and misinformation,” according to a 2012 article on mood and menstruation. “It became justification for restricting women’s participation in everything from sport to education to politics,” Schultz argues in her book, Qualifying Times: Points of Change in U.S. Women's Sport.

In 1964, researchers surveyed Olympic athletes competing in Tokyo and determined that competition had few detrimental effects on menstruation and pregnancy. Surprisingly, athletes who bore children prior to competing reported that they “became stronger, had even greater stamina, and were more balanced in every way after having a child”—a notion echoed by multiple later studies.

Despite these efforts, available research on women still lagged behind. “The amount of information available in determining women’s physiological response to exercise is relatively small in comparison to that available for men,” writes Drinkwater in 1973.

The passage of Title IX of the Education Act of 1972 opened up opportunities for women athletes and the researchers who studied them. The historic legislation required that women be given equal opportunity in education and sport, marking the most significant turning point in the history of women’s athletics. Before this mandate, there were fewer than 30,000 collegiate women athletes in the United States. But over the next four decades, that number would increase to 190,000 by 2012, according to a White House press statement. Title IX is a national, not international, initiative. Yet, as Sutton points out, the influence of the United States on the world has had a global impact on girls in sport.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/a4/27a44228-f842-4a70-8b8e-c6e8877673f2/birch111.jpg)

The Trouble With Gender

On the world stage, women have gone from being banned from competition to to performing feats that appear superhuman. But with these triumphs came pushback. Women who performed “too well” were viewed with suspicion, and often forced to submit to gender tests, an indignity never asked of their male counterparts.

Since the early 20th century, the IOC and IAAF had focused an inordinate amount of resources on trying to discover men posing as women in competition. But they found no imposters, only identifying intersex women who demonstrated that gender is not as binary as many believed at the time, and still believe today.

One of the biggest gender scandals was the case of Heinrich “Dora” Ratjen, who placed fourth in the 1936 Olympics high jump competition. At birth, Ratjen was classified by doctors as as female, likely confused by unusual scar tissue on his genitalia, later documented on medical examination. So Ratjen was raised as a girl, but long harbored suspicions that he was male. It wasn’t until 1938, when a police officer stopped him on a train for appearing to be a man in women’s clothing that Ratjen was forced to reckon with his gender identity.

As discussed earlier, the influx of Soviet women to the competition had forced the U.S. to up their game—but that also came with a twinge of gendered assumptions about what an athletic woman looked like. “The specter of these muscular women from Eastern European countries turned off a lot of North American audiences,” says Schultz. (It was later shown that the athletes were being fed anabolic steroids under the guise of vitamins in a state-sponsored program.)

In the two years leading up to the 1968 Olympics, officials began gender testing elite female athletes on a trial basis through demeaning genital checks later called the “nude parade.” To quell the rising tide of complaints about these humiliating tests, the IOC adopted chromosomal testing for women competitors in the 1968 Games. But the chromosome tests were far from reliable. “[T]he test is so sensitive that male cells in the air can mistakenly indicate that a woman is a man,” according to a 1992 New York Times article. And what the test results meant remained unclear.

The list of confusing outcomes from the chromosome and hormone tests is extensive. Ruth Padawer explains for The New York Times:

“Some intersex women, for instance, have XX chromosomes and ovaries, but because of a genetic quirk are born with ambiguous genitalia, neither male nor female. Others have XY chromosomes and undescended testes, but a mutation affecting a key enzyme makes them appear female at birth; they’re raised as girls, though at puberty, rising testosterone levels spur a deeper voice, an elongated clitoris and increased muscle mass. Still other intersex women have XY chromosomes and internal testes but appear female their whole lives, developing rounded hips and breasts, because their cells are insensitive to testosterone. They, like others, may never know their sex development was unusual, unless they’re tested for infertility — or to compete in world-class sports.”

Amid complaints from both athletes and the medical community, the IOC resolved to end Olympic gender verification in 1996, abolishing the practice by 1999. But suspicions of gender cheating were aroused again when runner Caster Semenya dominated the 800-meter race in the 2009 African Junior Championships, leading Olympic authorities to require her to submit to sex testing after that year’s World Athletics Championship.

This led the IAAF to implement mandatory tests for hyperandrogenism, or high testosterone in 2011. Women that test positive have two options, Schultz says, they can either drop out of the sport or undergo surgical or hormonal intervention to lower their testosterone levels. But it still remained unclear if naturally high testosterone levels truly give women an extra boost.

Men are not subjected to any of these tests—their whole range of genetic and biologic variation are deemed acceptable, Schultz adds. “We don't say that it's an unfair advantage if your body produces more red blood cells than the average male,” she says. “But we test for testosterone in women.”

Beyond the physiological aspects of gender testing is a broader social problem. “They say they don't sex test anymore, but that’s just semantics,” says Schultz. “It’s still a sex test, they're just using hormones instead of chromosomes to test for sex.”

The Modern Sportswoman

As research into women’s physiology has continued to expand, women’s athletics have made leaps and bounds. Title IX provided an influx of much-needed resources for female athletes, coaches and researchers.

Of particular importance was funding for female weight rooms, says Sutton, an initiative that was yet another response to the Soviet training regimen. Pumping metal meant the American women athletes could train harder and smarter—strengthening their bodies while preventing injuries.

Medical researchers have realized that women are more prone to specific injuries, Sutton explains, such as tears in the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)—a result of anatomy. Though women can’t change their bone structure, they can change the muscles supporting it. “Strength and conditioning coaches weren't seen as instrumental as they are now; now they're just as key as your nutritionist, your athletic trainer,” she says.

Despite these advances, today’s athletes still must contend with some lingering Victorian-age logic. Just this week, Chinese swimmer Fu Yuanhui, clearly in pain, mentioned in a post-race interview that she was on her period. Many applauded her for freely speaking about menstruation in public. But the fact that this made headlines at all emphasizes the stigmas that still surround periods.

Still, unlike in 1896, women are an integral part of the Olympic narrative today, and the women in this narrative are more diverse and inclusive than ever before. In an Olympic first, in 2012, every country sent at least one woman competitor to the London Games. Though many countries have yet to move past token representation, there is a long road ahead. Just as the Rio Olympics will turned to face Tokyo in the closing ceremony, the future beckons and the Olympic flame looks bright.

While there are many more chapters to unfold, for now, we'll end it with a period.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)