The Man Behind Lincoln’s Inauguration Photos

A new book celebrates the work of John Wood, the country’s first federal photographer

:focal(712x366:713x367)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f3/a3/f3a311e0-ced4-4c46-9353-4440af5e0142/lincolns_inauguration_from_book.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/b9/03b908d8-19c9-4cc9-89a6-2e6c8f625870/the_lincoln_column.jpg)

The symbolic nature of this column cannot be denied. Hewn from a single block and set in place on the architectural embodiment of the federal government, the monolith was a physical representation of the union of the states. Its name, The Lincoln Column, expressed the hope that the incoming president would somehow be able to hold the fractured country together. Wood chose to capture the monolith just as it was lifted. Gleaming and fragile, held only by the top, it was as delicate and vulnerable as the Union itself.

Wood made this print from an enlarged stereoview negative, which he then masked to alter its nearly square aspect ratio into a tight rectangular format. His deliberate editing deemphasized the building, drawing the viewer’s eye to the main subject, the column. Wood rarely took the time to make such adjustments in his work. Most images were printed as shot. The thoughtful alterations here perhaps indicate a special regard for the subject. This photograph was appropriately preserved in the album of Benjamin B. French, a staunch Lincoln supporter and master of ceremonies for his inauguration. It is French’s inscription that identifies the column’s special significance, a singular document memorializing a presumably surreptitious act.

On the morning of March 4, 1861, the inaugural procession began at the Willard Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue. As the procession made its way to the Capitol, Wood was busy setting up his equipment on its grounds. Standing on a large wooden platform, well above the crowds to the side of the stage, he had a privileged view of the scene. Six of Wood’s images survive from that day, most taken with his stereo camera. Located in disparate collections, the stereo-captured images remained static, but when reunited and placed into sequence, they become a dynamic document of what it must have felt like to be there. The first two images, taken only minutes apart, show a gathering multitude. Men have already begun to climb trees in anticipation, securing their bird’s-eye view. As shadows begin to move across the curved platform constructed over the Capitol’s main staircase, someone delivers a water pitcher for the speaker’s table. In the third frame, esteemed guests and musicians start to take their spots on the side stage, while a tuba player in the front inspects his horn. Two children stand in the foreground facing away from the stage, perhaps distracted by the cameraman and his equipment; the shadow on the platform again indicates the passage of time. Finally, in the last frame, Lincoln has taken his place under the pergola. The musicians have lifted their horns and several members of the crowd have turned to observe Wood as he takes his shot. With a filled stage and the multitudes all around him, he captures the new president delivering his first inaugural address.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/49/8c/498c27ea-63c4-4873-b53e-5385dae1dc0c/lincolns_inauguration1.jpg)

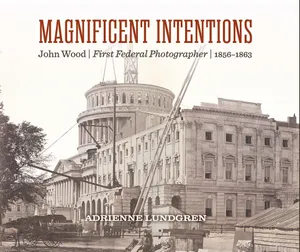

Magnificent Intentions: John Wood, First Federal Photographer (1856-1863)

Offering a unique glimpse into American history, this is the first book to celebrate the compelling work of the United States' first federal photographer. Features 160 photographs capturing Washington, DC as it developed and in the midst of Civil War.

Very few images remain of Lincoln’s first inauguration, and all the extant examples were taken by Wood. Naturally, other photographers were present to cover the event. An account in the New York Tribune reports at least three onsite that day, stating:

Several of those indefatigable persons, photographers, were on the ground to take impressions of the scene—one corner of the portico being occupied by the requisite chemicals, etc. A small camera was directly in front of Mr. Lincoln, another at a distance of a hundred yards, a third of huge dimensions on his right, raised on a platform built especially for the purpose.Famed Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner, manager of Mathew Brady’s Washington gallery, did not produce any known views of the event, but he was surely among the group, as well as New York photographer George Stacy. However, the last sentence in the paper surely referenced Wood, who took an enormous view that day measuring 15 × 18 inches (31.1 × 45.7 cm), obviously requiring a camera of “huge dimensions.”

Before now, John Wood had never been identified as the photographer behind the lens of these historic images. The most well-known view, the last in the series, had routinely been attributed to Gardner, as no one else in Washington, DC, was known to be working on such a large scale. Though Wood was working with much larger plates, even as early as 1856, the nearly square format of this view was unusual within his work. Only by examining the surviving examples collectively can one clearly determine that all four images were shot as stereoviews, the more sizable prints made through enlargement. Together, they definitively confirm that all were taken by the same person—the angle on the scene, the camera hardly moving between the exposures, and their nearly square aspect ratio consistent.Verifying that the same individual took these images was key to their collective attribution. In addition to their provenance, which connected them all to individuals associated with the Capitol extension, a published woodcut engraving clearly referencing the last print in the series definitively established that they were made by Wood. Though the artist took some license in extending the composition to create a more rectangular format, the angle of the shot and the presence of the figures in the trees matched the photograph precisely. At the bottom of the engraving is the text, “The Inauguration of Hon. Abraham Lincoln, Photograph by Mr. J. Wood.” The image was accompanied by an article stating that the source print was obtained through Montgomery Meigs and taken by his photographer.

When viewed next to their stereo-sized counterparts, the two enlargements of the Lincoln inauguration are a testament to Wood’s ability as a reprographic photographer. Methods for producing photographic enlargements were described in the literature but focus on the use of the Woodward Solar Enlarger, a device that utilized a mirror and condenser lens to channel the sun’s ray through a negative, projecting a positive image onto a sheet of sensitized paper. However, the Woodward exposures were long, requiring the user to adjust the mirror constantly to follow the sun. Thus, the results from such a device were not optimal, usually requiring hand embellishment to overcome their soft, diffuse appearance.Another method for producing an enlarged image was to rephotograph a smaller print, much as Wood had done when photographing drawings for the Capitol extension. The final size of the resulting image was determined by the distance of the camera relative to the original piece. When substantially enlarging a small image, the resulting negative would reflect a significant loss of detail and crispness because of the rendering of the paper surface. Both methods described above have led many scholars to believe that high-quality photographic enlargement was not possible in the nineteenth century and that, if attempted at all, the loss of resolution would be so profound that the results would be immediately recognizable.

Wood’s enlargements are not readily identified as such, as the image quality is still highly resolved. This strongly suggests that he employed an alternate technique, utilizing a little-known instrument referred to as a “photographic pantograph."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/59/87/59874533-616d-4c77-9f3e-ff29b0e14894/photographic_pantograph.jpg)

This copy device, not widely in use until 1857, first required the creation of an inter-positive glass plate.This was made by placing the original negative directly onto a dry collodion plate and exposing it to light. The resulting positive, (c) in the image above, was processed, fixed, and dried and then placed into the open end of an otherwise light-tight box. Near the center, a lens was positioned at a calculated distance (b), and at the other end of the box, a receiving plate (a). In Wood’s case, this plate (a), measuring roughly 14 × 14 inches (35.5 × 35.5 cm), was substantially larger than the original negative of 2.8 × 2.8 inches (7.1 × 7.1 cm). The pantograph was then positioned in a window facing the sun. The dark slide was pulled to allow the sun’s rays to pass first through the inter-positive, then the lens, projecting the image onto the new plate and creating an enlarged negative. By adjusting the distance between the two plates (a and b) and the lens (c), various levels of enlargement could be achieved. The exposures were very short compared with a solar enlarger—a matter of seconds because of the relative speed of collodion negatives to that of printing papers. But the real advantage of this method was that “collodion give[s] results of almost microscopic minuteness, [and] such negatives bear enlarging considerably without any perceptible deterioration.”

Thus, the enlargements that Wood produced from his stereo-sized negatives are truly remarkable. His resulting prints show almost no discernable loss in resolution. While clearly successful, this technique required a high level of expertise and thus was not widely employed. Minor errors relating to exposure, focus, and contrast would be magnified in the final printed image. The process demanded precision and expert judgment at every step to produce a photographic print that appeared equal to one made from a camera-produced negative. However, when done well, the resulting prints are crisp and detailed and show little evidence of this multi-stepped process.

Besides the images he shot from the platform, Wood also produced a more distant perspective that day. The final image in the previous series showed Lincoln as he delivered his inaugural address; this one, when examined closely, indicates that it was taken later, likely during his oath of office. For this view Wood stepped back behind the crowds, perhaps at the location “100 yards away” as noted in the newspaper. The building, rather than the event, dominates the scene. Pieces of marble still awaiting placement on the facade populate the foreground, and behind the trees to the left, just visible, is the wooden platform and ladder where Wood stood to take his earlier images. This photograph, unlike the others, was taken on an impressive 15 × 18 inch (38.2 × 45.7 cm) format plate, again demonstrating Wood’s mastery of outdoor photography on a monumental scale. The focus, though slightly soft, gives a full impression of the building while still offering an intimate peek at the ceremony framed between the trees. The Capitol’s extension wings were nearly complete except for their respective pediments, and the mammoth dome towered overhead, gleaming in the light.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/26/e3/26e3c4a6-273b-4f50-b2ff-651fb55c9085/the_inauguration_of_mr_lincoln.jpg)

The Lincoln inauguration was a turning point for the United States. Southern Democrats who supported the continuation and expansion of institutionalized slavery took the president’s inaugural speech as an overt condemnation of their way of life. Lincoln, ever the lawyer, attempted to argue the illegality of secession. Addressing Southerners, he presented the advantages of the democratic system. By trusting the process and staying united, Lincoln argued, the right and just path would be revealed.

The public was acutely aware that there was little possibility that Lincoln’s words would alter the nation’s current course. Having witnessed firsthand the heated debates in the Capitol, Wood had an insider’s view of the storms that were on the horizon. Counting down the exposure and securing the lens cap back in place, he captured a key moment, a tipping of the scales.

Magnificent Intentions by Adrienne Lundgren is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Magnificent Intentions: John Wood, First Federal Photographer (1856-1863) © 2024 by Library of Congress and Smithsonian Institution

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.