The Many Faces of Mt. Everest

A new book commemorates 100 years since the infamous 1924 expedition

:focal(800x610:801x611)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/07/aa/07aa6308-13ef-49e9-8af6-f8169c9f990d/79.jpg)

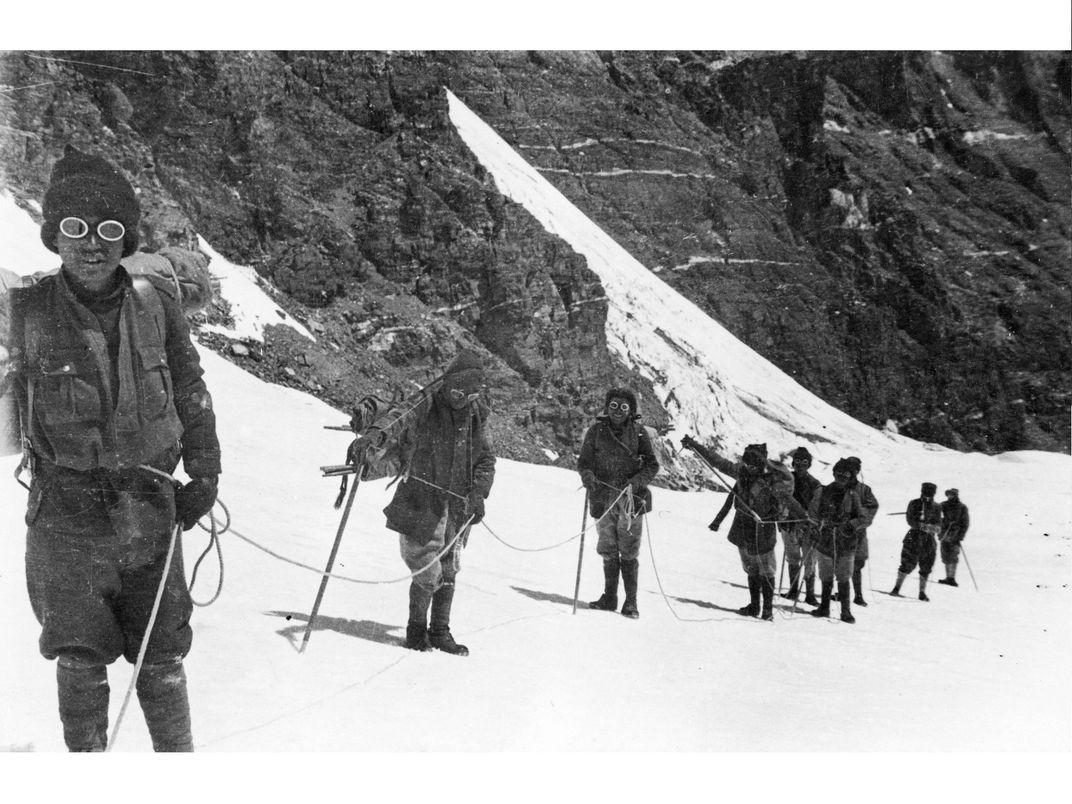

The 1924 Mount Everest Expedition was an incredibly important moment in the history of Himalayan mountaineering. It was the culmination of two prior expeditions and cemented a global public fascination with the mountain, which at 29,032 ft is the tallest in the world. The unparalleled coverage of the 1924 expedition – memorably captured on film by the official photographer John Noel and shown across the world in the resulting feature film The Epic of Everest – combined with the drama surrounding the disappearance of George Mallory and Andrew Irvine, placed the mountain squarely in the Western public mind.

After the return of the 1924 Mount Everest Expedition, Mallory and Irvine were mourned at St Paul’s Cathedral, celebrated at the Albert Hall and projected on cinema screens across Great Britain. John Noel’s film The Epic of Everest opened in London with a live prologue featuring Lhakpa Tsering, a Sherpa porter at Mallory and Irvine’s highest camps, and music, chants and dances performed by a group of seven Buddhist monks from a monastery at Gyantse, Tibet. Controversies over these “dancing lamas” led to a breakdown in Anglo–Tibetan relations and the cancellation of Mount Everest expeditions for almost a decade. The expedition and film also illustrate the enduring intercultural consequences of the 1924 Mount Everest Expedition, which extended from Britain to the Himalayas.

Noel’s film depicted a cinematic struggle of inquisitive white men against a mystical mountain. After the tragic deaths of Mallory and Irvine, the film asked whether Everest was more than a mountain of rock and ice and snow, but alive and guarded by the spirit of Chomo-lung-ma (Goddess Mother of the World): “Strangely to memory the words of the Rongbuk Lama come: ‘The Gods of the Lamas shall deny you White Men the object of your search.’” The film then closed with close-ups of the Rongbuk Lama followed by time-lapsed views of clouds, sunset and Chomolungma from the monastery as darkness falls.

The visit of the “dancing lamas” brought this narrative to life and created a sensation in London. Much of the British press adopted a tone of superiority and mocked the lamas’ visits to the zoo, shops and a Punch and Judy show. They also misconstrued their reaction to London as a fear of technology and “white man’s magic”. The Head Lama, Gana Suta Chenpo, told The Times he regretted so few people did any real work in London, since they relied on machinery and would be destroyed by their machines. Rinchen Lhamo, a Tibetan woman living in London, recognized this critique as the remark of an acute observer and wondered whether journalists could not understand it due to orientalist stereotypes that Tibetans were primitive.

Everest 24: New Views on the 1924 Mount Everest Expedition

Commemorating the 100th anniversary of an enduring Everest mystery, this book sheds new light on the ill-fated 1924 Mount Everest expedition Features unseen and rarely seen expedition images and cultural perspectives on the world's highest mountain

Leaders of Tibet, Sikkim and Bhutan were offended in various ways – by scenes in the film, the expedition’s unauthorised detours in Tibet, and newspaper photographs of the “dancing lamas”. Indeed, officials from Sikkim and Bhutan saw the film in Darjeeling and objected to scenes that were later cut. The climbers had also travelled beyond the areas authorized by their climbing permits. While Tibetan officials forgave the climbers’ trespasses in Tibet, in 1925 they regarded taking the monks to London as “very unbecoming. For the future, we cannot give them permission to go to Tibet.” The Dalai Lama saw pictures of the “dancing lamas” in newspapers and viewed the affair as an affront to Tibetan Buddhism.

The “dancing lamas” also played a decisive role in undermining the reputation of the military in Tibet. In 1921, Tibet had given permission for the first Everest expedition in exchange for British weapons. The dancing lamas controversy was one of several events in 1924–25 that tipped the balance of power in Tibet from the military to the monasteries. When border conflicts escalated in the 1930s, Tibet again turned to the British for weapons and began giving Everest climbing permits as welcoming gifts to British envoys visiting Lhasa. The Tibetan military never recovered from the loss of support from the Tibetan elites in the 1920s and it was too weak to stop invading forces in the 1950s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/24/87/2487ee8a-8142-4952-992c-e17f89385b09/11.jpg)

Elsewhere in the Himalayas, the porters returning from the 1924 Mount Everest Expedition inspired others to follow in their footsteps. Ang Tharkay and Tenzing Norgay became porters on Everest after hearing about the 1924 expedition and later took leadership roles on Annapurna and Everest. One of Ang Tharkay’s friends returned from Everest to Khunde, in Nepal, strutting about with his climbing gear as if he had accomplished something awe-inspiring. Tharkay remarked: “As I was younger than he was, my imagination ran wild when I heard his sensational description of his adventures. I was so impressed that I immediately felt an uncontrollable desire to follow his example and to try to join an expedition myself.” Tenzing Norgay developed the same ambition after hearing stories about big boots, strange clothes and Everest. “What is Everest?” Tenzing asked. “It is the same as Chomolungma,” replied Sherpas who had climbed on its other side, in Tibet.

Collaborative expeditions to Everest initiated in the 1920s were crowned by the first ascent by Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary in 1953. After reaching the summit, Tenzing and Hillary both looked for traces of Mallory and Irvine but could not see any. Tenzing recalled hearing the names of Mallory and Irvine in the 1920s and never forgot them. They descended to Camp IV where the 1953 film crew recorded their joyous reunion and celebrated the teamwork of Sherpas and Sahibs alike, and all who had come before. Amid the celebrations, Hillary told one of the other climbers, Wilfred Noyce, “Wouldn’t Mallory be pleased if he knew about this?

Climbers from around the world have been fascinated by the fate of Mallory and Irvine. Chinese climbers made the first ascent of Chomolungma from the north in 1960. When they climbed the route again in 1975, a Chinese climber reported seeing the body of “English dead”. On the north side in 1980, Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner had visions, heard voices and sensed the spirit of Mallory and Irvine during his solo ascent of Everest without bottled oxygen. Even after the discovery of Mallory’s body in 1999, the fate of Mallory and Irvine has remained the subject of continuing speculation along with search parties funded by cinematic reenactments and commercial documentaries.

All too often, the 1924 expedition is remembered as a “pure” adventure before Everest became crowded and commercial. Nostalgia for lost colonial privileges is one of the expedition’s legacies. But nostalgia should not obscure the deeply commercial character of the 1924 Mount Everest Expedition, which was funded by John Noel’s film company and publicized by orientalist images of white men overcoming superstitions in Tibet. Reactions to the interplay of climbing and commerce were as intense then as they are now, a century later. The worldly connections set in motion on Everest in 1924 are still at work among us.

Everest 24 is now available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

"The Many Faces of a Mountain" by Dr. Peter H. Hansen excerpted from Everest 24 © Unipress Books Ltd 2024; Images © copyright Royal Geographical Society

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.