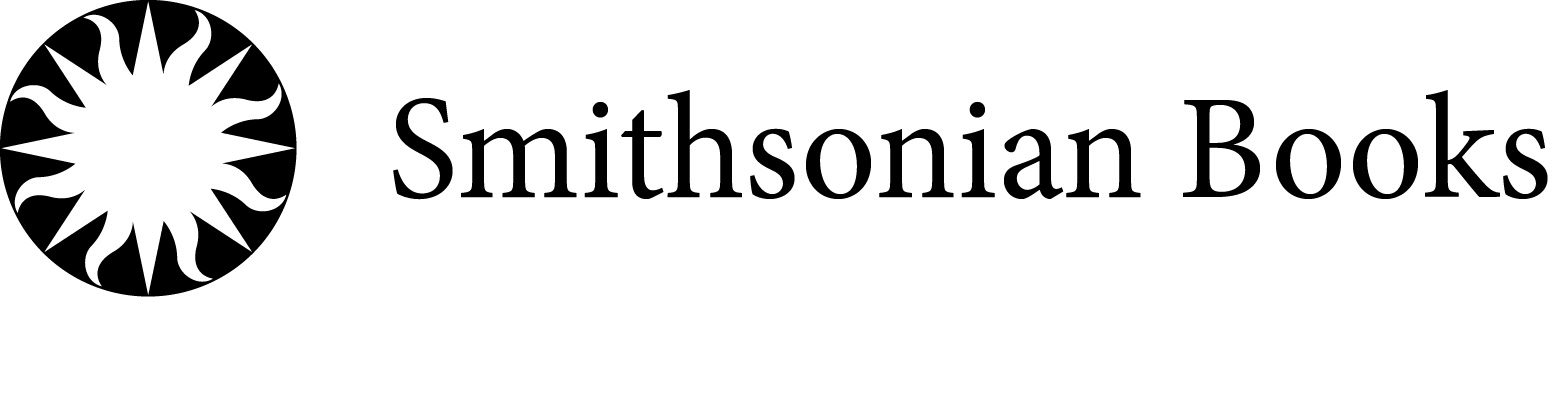

How Do Teachers Spend Summer Break? These Two Spent Theirs in a Bomber Factory

Learn about the experiences of women supporting World War II efforts in the memoir “Slacks and Calluses.”

:focal(326x226:327x227)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/25/34/25347bca-8a27-42e6-98e8-55661bb0102c/riveting.jpg)

Anybody can build bombers—if we could.

We were the kind of girls who knew nothing about airplanes except that they had wings and they flew. When one flew overhead we waited until somebody said, "That's a Liberator!" Then we looked into the sky and echoed wisely, "Yes, it is, isn't it?" We were not sure then whether a Liberator was an army or a navy plane, or whether it was a bomber or a fighter; and we had not yet discovered that a B-24 and a Liberator are exactly the same thing.

Perhaps that was why people laughed when we announced that the aircraft industry wanted us to build bombers during summer vacation. Perhaps that was why they rolled on the floor and shrieked.

"You build bombers!" they howled. "An art teacher and an English teacher!" ·

That was the way they said it, laughing uproariously—just as if an art teacher and an English teacher couldn't build bombers. That was enough for us. Clara Marie said by golly, she could build bombers and I said by golly, I could too, although I wasn't quite sure what either of us could do to bombers—that would be useful. Anyhow that was the aircraft industry's problem. They needed help. They wanted school teachers to work during summer vacation. O.K., they had to find something school teachers like us could do.

At least we let the aircraft industry know what they were up against, for we filled out our applications for employment with perfect honesty—putting "No" or "None" after every question. Then, a little embarrassed at our own effrontery in thinking we could be of any use on the production line, we took our applications down to the Employment Office. We maneuvered our swooping hats into position before a tiny window which was presided over by a clerk whose name, according to the little metal standard at her elbow, appropriately was Mrs. Hires. We deposited our applications timidly in front of her.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bd/61/bd6142da-eedd-4a70-9c74-3d453bf3d31e/slacks_and_calluses_illustration.png)

Mrs. Hires, to our amazement, greeted our applications with expressions of joy. She didn't even look at the "No's" and the "None's." She didn't seem the least bit worried about what we could do on the production line. She just wanted to be sure that we understood ours would not be clean jobs. She asked twice did we understand that we would get our hands dirty. As soon as we had assured her that we understood—we were hired!

"What shift do you want to work?" she asked.

"What shifts do you have?" parried C.M., who is like that, while I said quickly, "The Swing Shift.'' (The Swing Shift pay-rate, which is eight cents more an hour than the Day Shift, was a useful item of information I had gleaned from a theme on "My Job" in my first period English class, the theme explaining incidentally why the writer usually slept through first period English, if he got there at all, which he usually didn't.) ·"Which plant?" Mrs. Hires asked patiently, explaining that the Swing Shift at the Main Plant was from 4:30 to 1 and the one at the Parts Plant from 2:30 to 11.

C.M. looked at me, and I looked at her, and we both did some rapid figuring about getting up and going to bed and getting our summer tans on the beach."4:30 to 1," said C.M.

"4:30 to 1," I said.

Mrs. Hires looked pleased. She said that people were needed on that shift.

Slacks and Calluses: Our Summer in a Bomber Factory

At times charming, hilarious, and incredibly perceptive, Slacks and Calluses brings into focus an overlooked part of the war effort, one that forever changed the way the women were viewed in America.

"Now what do you want to do?" she asked, and the way she asked it sounded as if she meant what could we do.

"What can we do?" we echoed plaintively.

Mrs. Hires opened an official-looking folder.

"Well," she said, as if it were not too difficult a problem, "filing," (filing metal, not cards, she hastened to explain), "riveting, sub-assembly, final installations—"

"Final installations?" we demanded, snatching at the word Final. "Actually in the plane?"

"Yes, actually in the plane,'' she said.

"Are you sure," I said cautiously, for after all we were patriotic Americans, "are you sure that we can make final installations?"

"Oh, of course, anybody can," she said carelessly, and she made strange little marks on our applications and wrote our names in the spaces marked "Last Name First" and sternly stamped in red "Applicant Will Not Write His Own Name Here."

"Now this will expedite matters for you," she told us. "YOU will report here Monday morning at 8 o'clock, and I will have your applications checked by then. That will expedite your Employment Induction," she pointed out sweetly.

Expedite, she said. That was undoubtedly the favorite word of the aircraft industry; and if at the time we thought that the aircraft industry didn't know what it meant, that was before we had been "expedited" through the conveyor-belt process known as Employment Induction.

Our Employment Induction began at 8 o'clock Monday morning when we graciously announced to Mrs. Hires that we were now ready to build bombers, and it ended at 10 o'clock when we and our personalities had been reduced to half a hundred forms, cards, folders, and contracts, all signed in duplicate "where the check is, please."First, Mrs. Hires gave each of us a bulging 9 by 11 manila envelope which contained seven handbooks and pamphlets, a list of regulations for women's work clothes, a list of the tools we would need, a copy of The Consolidated News, and a membership card for the aircraft union. She said she thought the envelope contained all the information we would need. We thought that it must.

"Do you have any questions?" she asked. She knew that we didn't, because she had just said that all the information we would need was in the envelope; but evidently she liked to prove to herself the super-efficiency of the Employment Induction: Every question answered before it was asked.

"Just follow the instructions on the envelope-and follow the yellow line on the floor,'' she told us.

We followed the yellow line around the corner and into a large office where there were at least three dozen desks, each complete with typewriter and typist. C.M. and I took our places on the row of chairs along the wall and inspected the other new employees who were there ahead of us. They were evidently the scrapings from the manpower barrel-like us. Older women and old men. Scrawny mothers with children tugging at the hems of their housedresses. Fuzzy high school boys.

There were nine steps listed in the procedure for Employment Induction, which was mimeographed on the front of our envelopes; and there were about that many physical steps, since we usually moved from chair to chair and desk to desk as different girls, all spreading at the hips, all wearing glasses, all glancing worriedly at the sheets in their typewriters, called "Bowman!" or "Allen!," never looking up to see who Bowman or Allen was as we handed over our envelopes. This way we moved down the yellow line, the envelopes growing bulkier at each step.

Step one.

The Requisition Clerk entered on a permanent record our names (now officially C.M. Allen and C.H. Bowman), our job classification (unclassified and unskilled) , our starting date (Wednesday afternoon at 4:30), and our rate of pay (60 cents an hour with an 8 cent bonus for the Swing Shift).

"Do you have any questions?" she asked, stuffing more bright colored sheets of paper into our envelopes.

We didn't.Step two.

The Physical Appointment Clerk filled in a description of each of us on half a dozen assorted identification cards. She looked disapprovingly at C.M.'s personal description as it was checked in on her application. Then she looked at C.M.'s eyes.

"I'm sorry,'' she said, "but we will have to change the color of your eyes. We don't have green eyes here."

"Do you have any questions?" she asked absentmindedly as she crossed out "green" and wrote "hazel" after "Color of Eyes."

We didn't.

Step three.

The Birth Certificate Clerk was having her troubles as we arrived.

"I wired for my birth certificate," wailed the girl in front of us, "but they just wired back a list of lawyers who can start proceedings to prove that I was born!"The Birth Certificate Clerk took our birth certificates and scrutinized them carefully. She seemed to be satisfied that we had been born.

"Do you have any questions ?" she asked as she returned them to us.

We didn't.

Step four.

The Clock Clerk gave us each a number (4126 for C.M. and 4042 for me) and said sternly that we should read the instructions which we would find in our envelopes on punching in and out at the time clock. We had already read the instructions, which had sub-points lettered from "A" to "J," and we were already convinced that we were utterly incapable of coping with a complex machine like a time clock.

"Do you have any questions ?" the Clock Clerk said, quickly handing back our envelopes so that we wouldn't ask any.

We didn't.Step five.

The Identification Clerk filled out a stack of cards for each of us and then shoved them across the desk for our signatures."Do you have any questions?" she asked as C.M. scrawled her name and I laboriously drew mine so that it would be legible.

We didn't.

Step six.

The War Manpower Commission Availability Certificate Clerk (whew!) asked us if we had Availability Certificates. When we admitted that we didn't, she said well, she didn't think we needed them anyway.

"You are available," she said, as if it were the only thing she could find in our favor.

"That's us," said C.M. cheerfully. "We are available."

"Do you have any questions?'' asked the clerk, ignoring this small pleasantry.

We didn't.

Step seven.The Fingerprint Clerk greeted us briskly.

"Put your purse here," he said to me as we came in. "Put your glasses there. Get in here. Stand there. Look here." He held a card up under my chin. I didn't know whether it was a name or a number, but I smiled my most bewitching smile, which looked like a leer when I saw it later on my identification photo. Since my smile had obviously been a failure, C.M. tried an expression of haughty interest when it was her turn. It also looked like a leer on the finished photo.

"Re-lax!" the clerk instructed me, taking my right hand firmly in his as if it didn't belong to me at all. He rolled my thumb on the ink pad and then on the card with a rocking motion like that of a waltz—if a waltz had two dips instead of one. While my hand was practically waltzing without me, I tried to follow with the rest of my body. I had the embarrassed feeling I have when I step on my partner's toes. C.M. watched me carefully so that she would do better, which she did.

"Do you have any questions?" asked the Fingerprint Clerk as he studied my left thumbprint critically. He was obviously a master who had fingerprinted gangster kings and stock exchange presidents.We didn't.

Step eight.

The Physical Examination Clerk, efficiently clattering on her keyboard, typed out our medical folders without an error. The nurse, letter perfect, rattled off a list of peculiarly uncheerful ailments in double time.

"Did you ever have rheumatism? Kidney trouble? Typhoid? Small pox? Syphilis? Cancer? Varicose veins?"We said, "No. No. No." Sometimes we stuck in an extra "No" and sometimes we got behind and missed one. Once we said "No" from force of habit when we should have said "Yes."

The second nurse, efficient as always, snatched us up as we said the last "No" and assigned us to barren little individual dressing rooms. A few minutes later a third nurse called "Bowman!" and "Allen!," and the rest of the physical examination was like any other—poke, push, probe, and punch.

The blonde girl in front of me, whose mother hovered over her even in the doctor's office, was illiterate, as the nurse discovered when she tried to give her an eye test. The nurse told us that she was the first illiterate in nearly a thousand women, although the rate among the men hired was higher. C.M. said she supposed that illiterate men had to get jobs while illiterate women had children. The nurse said that she supposed so, and deposited us again in the little dressing rooms.

"Do you have any questions?" she called after us a few minutes later as we followed the yellow line back into the Employment Office.

We didn't.

Step nine.

The Final Induction Clerk, calling "Bowman!" and "Allen!" for the last time, put a sheaf of papers in front of us for us to sign, most of which involved reducing our pay checks by bond, tax, and insurance deductions. I unsuccessfully tried to subtract all these from 68 cents times 52 hours, which I was multiplying in my head. Some of the papers were in very fine print, which we conscientiously tried to read before we signed them. One was an Invention Agreement "'entered into by and between Consolidated Vultee Aircraft (hereinafter called the Company) and Constance Hall Bowman and Clara Marie Allen (hereinafter called the Employees). Witnesseth ; in consideration of the mutual undertakings hereinafter set forth, the parties hereto do hereby agree as follows:" the general idea being that if we built better mousetraps, Consolidated could keep the world from our door. We thought that it was very flattering of Consolidated to be so interested in our inventions, although we could have told them they wouldn't be worth the trouble.

We also signed a sheet saying that we had read the Espionage Act, Executive Order of the President of the United States, No. 8381; and that we had been warned that many of the projects carried on by the company were classified as Secret, Confidential, and Restricted. C.M. asked the Final Induction Clerk how we would know whether a project was Secret, Confidential, or merely Restricted. The clerk merely smiled wisely and said, "You'll know."

"Probably the guard will say "Shhh!' when we go in," I whispered to C.M./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2d/ed/2dedd7f2-bbe6-4729-aaac-ec2ba9fb6c28/b-24_liberator.jpg)

"Now," said the Final Induction Clerk with a sigh as she wrote down on our envelopes the same instructions she was giving us, "you will report to Gate Two, Plant One, at 4:30 on Wednesday afternoon. Wednesday afternoon," she repeated. "You will be unclassified helpers, final minor installations on the B-24's."

"On the big bombers?'' we asked.

The Final Induction Clerk smiled kindly and said yes, on the big bombers.

"Do you have any questions?" she asked, confidently, because she knew we couldn't possibly have any. It was the final test of the efficiency of the Employment Induction.

We said no, we didn't have any questions. If we had had the strength to think of any, we wouldn't have had the strength to ask them. We felt as weak as triplicate copies of ourselves. As we staggered out into the morning sunshine, C.M. cast a thoughtful if slightly jaundiced eye at the Army and Navy "E" flying on its own standard next to the American flag over the main entrance of the plant."The Army and Navy 'E'," she mused. "I bet the 'E' stands for expedite!"

Slacks and Calluses: Our Summer in a Bomber Factory is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Slacks and Calluses © 1999 by Smithsonian Insititution

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.