The ‘Friend to America’ Who Helped Recognize the Country’s Independence

Learn about the short-lived British prime minister who negotiated a peace treaty that ended the American Revolutionary War.

:focal(320x250:321x251)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/88/6d/886da7c5-d0be-4d7c-aaa1-510cfa512ab3/treaty_of_paris.jpg)

We celebrate July 4 to mark the 1776 ratification of the Declaration of Independence, but the British wouldn't recognize the United States as an independent nation until the end of the Revolutionary War. The treaty signed in Paris on September 3, 1783, by representatives of Great Britain and the new United States formally ended a grueling seven-year war. Negotiations over the contours of American independence among the two British and four American representatives had dragged on since April 1782.

The Pennsylvania-born artist Benjamin West sought to capture their achievement. Soon after preliminary articles of peace were signed in early 1783, he began work on a group portrait of the negotiators. Seated at the table are John Adams on the left; Benjamin Franklin in the center, staring straight out at the viewer; and Henry Laurens, whose head rests wearily on his hand, on the right. John Jay stands on the left side of the canvas, above Adams, pointing to Franklin, the most senior member of the delegation, while Franklin’s secretary and illegitimate grandson, William Temple Franklin, stands between him and Laurens. Documents crowd the table. Behind them, a window draped with thick curtains of a muddy chartreuse color opens onto a landscape with a white house in the background and an intense blue sky above it.

But the right side of the canvas is empty. West’s portrait of the peacemakers proved impossible to finish, despite the fact that, living in London, he was well situated to capture the characters of all concerned. Britain’s principal representative, the merchant Richard Oswald of London and Auchincruive in Scotland, and his secretary Caleb Whitefoord, do not appear: both Scotsmen were reluctant to be memorialized as the men who gave away the bulk of Britain’s North American colonies, especially after Parliament’s hostile reception of the preliminary articles struck on November 30, 1782. Always sensitive about his looks (some thought him ugly; he was certainly vain, needing spectacles and an ear horn but loath to use them in public), Oswald actively resisted sitting for West. Admittedly, it might have been inconvenient, as he resided in France and Scotland much of the time, but he also refused to allow the only portrait he had of himself — a primitive 1750 marriage portrait that he disliked intensely—to be used as a model. Just over a year after the signing of the definitive articles of the treaty, he died at his seat in Ayrshire.

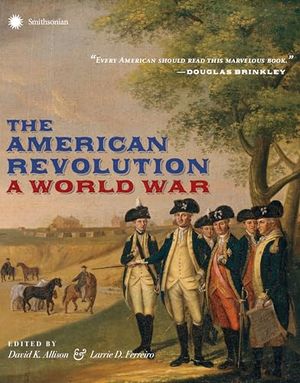

The American Revolution: A World War

A lavishly illustrated essay collection that looks through a global lens at the American Revolution and re-positions it as the real 1st world war

West held on to the unfinished oil sketch until his own death in 1820. Thereafter it passed through the hands of several collectors, including J. P. Morgan and H. F. du Pont, who made it a centerpiece of his new Winterthur Museum. Two copies survive—one in the diplomatic reception rooms of the U.S. Department of State in Washington, D.C., and another on a wall of the John Jay Homestead in Katonah, New York. The U.S. Postal Service clumsily reworked West’s image in a stamp issued to commemorate the 1983 bicentennial of the peace.

According to some historians and art historians, the absence of the British negotiators from West’s depiction symbolizes either the division between the mother country and its former colonies or an assertion of American independence and will. These conclusions are implausible. We know the omission was not West’s intention. More likely, the British negotiators’ nonappearance reflects their view that the former colonists were simply not the most important parties to the peacemaking — hard as that is for subsequent generations of Americans to fathom.

More striking in the lush visual depiction of the negotiations is the absence of the true architects of the peace: Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes, Louis XVI’s chief minister; and William Petty-Fitzmaurice, second Earl of Shelburne, George III’s prime minister. Too easily forgotten, these two political leaders deftly directed—and often micromanaged—the negotiations.

Historians often describe the peace the two ministers constructed in 1782 and 1783 as Britain’s caving in to the United States. Britain gave away so much, it is said, because the North American insurgents had won the war and then, with more wily and moralistic representatives, the negotiation; Americans gained so much because weak, gullible, and corrupt British ministers and negotiators had steered the ship of state to financial weakness and defeat. Historians treat Britain’s separate negotiations with France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic, as well as the United States’ dealings with them, as second-order diplomacy. This narrative is driven on the one hand by triumphalist American historians writing a victors’ account of the war and its aftermath, as those in any country are wont to do, and on the other hand by defeatist British historians who did not see much to extol in the huge losses of men and land (except for the expansion of territorial empire in Asia), and who saw in the loss of America a prefiguration of further decline two centuries later.

Through a twisting of historical sense, West’s painting can be made to fit the American narrative of superiority and dominance. But the reality is a much more complicated story, one that has to do with the British and European personalities involved in the peacemaking process; their philosophies, programs, and aspirations; and their need to consider one another’s motives—not just those of the Americans — in crafting the diplomatic outcome. That is to say, the British negotiators had more to consider than just the territory of the United States, its wily and moralistic negotiators, and American concerns. It was the British working in concert with the French who really commanded the peacemaking, and their leaders were, despite having been on opposite sides of the conflict, more united than divided.

Historians have looked at the negotiations variously. British historians such as Vincent Harlow in the 1950s argued that the peace was shaped by overseas and, to a lesser extent, domestic developments. The Crown and ministers preferred trade over territory, as exemplified in the “swing to the East” that supposedly recentered their empire in Asia during and after the loss of America. In contrast, American historians like George Bancroft in the 1870s and Samuel Bemis and Richard Morris in the 1930s and 1960s, respectively, adopted a moralistic and patriotic stance. For them, the peace was an unequivocal moral and strategic win for clever, superior Americans and a total loss for inept, inferior, and corrupt Britons.

However expansive their outlook, historians in both camps largely ignored what was going on in Europe, Africa and India. As the historian Andrew Stockley has suggested in the most thorough recent analysis of the peace, earlier scholars have failed to take account of the simultaneous discussions and negotiations being conducted between and among Britain, France, Spain, the Dutch Republic, Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, and Russia. There is another way to tell the story of the peace, Stockley suggests: analyzing its outcome as the product of more international, multivariant factors. Shelburne in London may be the most important party, inasmuch as he was the mastermind and midwife of four separate treaties.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/37/12/37125c58-d62f-4659-bf90-82cdb7836283/lord_shelburne.jpg)

Shelburne’s life, personality, and philosophy decisively shaped the diplomacy of 1782 and 1783, and he contributed to the highly interconnected European, Atlantic, and often global endeavor. While he was commonly referred to as a “friend to America” throughout the revolutionary period, when crafting and selling the terms of peace Shelburne did not consider or deal only with the former colonies and their negotiators. Indeed, his correspondence reveals that France loomed larger and more continuously in his mind, and other European states weighed on it heavily as well. In crafting the treaties, he adroitly balanced the desires and needs of the French, other Europeans, and Americans with those of Britain and its empire. In crafting solutions, he combined an idealistic, cosmopolitan philosophy and outlook with a pragmatic approach to problem solving that, at least in the short run, maintained the balance of power in Europe.

Shelburne was one of the most influential leaders of the late-eighteenth-century anglophone world. His family had lived in Ireland since the twelfth century and had adhered to the Catholic faith until the 1690s. He would inherit vast estates in Ireland, England, and America. He studied for several years at Christ Church, Oxford. He served as a volunteer military officer with the British army in France and Germany in the late 1750s. Although elected to the House of Commons in 1761 at age of twenty-four, he never took his seat: on the death of his father, he was elevated to the House of Lords, and there he sat for the next forty-four years, towering above his peers as one of the Whigs’ great orators and head of one of their many factions. An avid, informed “Improver,” he tinkered not only with soils and crops on his many Irish and English estates but also with economic, social, political, and religious practices throughout all of Britain in attempts to better his estate, his nation, his continent (for he thought of himself as also a citizen of Europe), and his empire. He died in London in his palatial Berkeley Square home in 1805.

Shelburne was a formidable intellectual and cosmopolitan figure who sought to advance literature, science, arts, religion, and society. He read and collected books in seven languages (of which he spoke four), amassing one of the largest and most influential private libraries in Britain. He visited Paris nearly every other year, purely for personal enjoyment. Abroad and at home, he gathered around himself some of the era’s greatest free thinkers, encouraging, imbibing, and promoting their work; to them, he evangelized about his belief in the unity of European and American culture.

The record on Shelburne’s personality is mixed. He was both much despised and much loved. He was called a Jesuit, or at least Jesuitical, a modern-day Malagrida (a Jesuit missionary who exerted great influence at the Portuguese court and whose name came to signify a smooth, informed but specious interlocutor). Because Shelburne was able to talk on any side of any issue, he was seen as insincere. To many, he appeared to possess no principles at all. He experienced frequent and often unpredictable changes of opinion and looked to others to influence him. He was accused of being a knave and a liar, deceitful, deceiving, or misleading. More, he was accused of double dealing, working to people’s disadvantage behind their backs. He also attracted and consciously gathered about himself not aristocratic peers but “the middling sort”—educated and professional men such as Adam Smith, Richard Price, Jeremy Bentham, Francis Baring, John Dunning, and Samuel Garbett.

After Shelburne became the prime minister in 1782, his contemporaries found new traits to decry. He was seen as having a “passionate or unreasonable . . . temper and disposition,” alternating between violence and equanimity. He frequently exhibited whimsical behavior. As one observer noted, he possessed “an inequality of temper” that made him difficult to please.

But was it true? Was this the same man who commandingly moved the items in negotiation like so many pieces in a cool game of chess? Along with his detractors, there were those who praised him—many in private but a few in public. As James Boswell observed toward the close of his Life of Samuel Johnson, “Man is in general made up of contradictory qualities, and these will ever show themselves in strange succession”. Shelburne was no different. But most of his peers and political contemporaries were not men of much introspection, and the roughly dozen highly damning traits stuck to his name, regardless of reality or relevance.

Greater insight into Shelburne and his dealings with fellow peers, politicians, and diplomats in 1782 and 1783 comes from realizing that he suffered from an inability to connect with others. Initially, his upbringing and his parents’ treatment of him left him feeling alone and unsure of himself. He suffered emotional trauma after the deaths of his three sisters during his childhood and the later loss of his two young wives, his second-born son, and his only daughter. Moreover, from birth, he coped with chronic eye and ear diseases. Finally, he experienced serious financial problems, always spending more than he earned and having to mortgage and remortgage his properties. He died a bankrupt.

Detachment greatly overshadowed anxiety in Shelburne’s psychological makeup. In particular, the effect of having two emotionally distant parents continued to affect his behavior even as an adult. Many of the traits identified by his political foes in 1782 and 1783 can be seen as those of someone who had for decades tried to keep people at a distance.

The dislike and envy felt by contemporaries, and Shelburne’s detachment from them, shaped his peacemaking probably more than anything else. By temperament, he was a lifelong compromiser. Throughout his long career in politics, he was willing to change his mind on particular matters when given more or different information. Unsurprisingly, this trait created difficulties for him by giving others the erroneous impression that he sought only to please others and exercise power. But in almost all cases, the turn had to do less with ingratiating himself with others than with confronting and embracing new information or a situation different from the one he had expected.

On occasion, Shelburne would concede on a matter of principle. From the start of the peace negotiations in 1782, for instance, he had wanted to defer the acknowledgment of American independence until the final terms had been crafted and confirmed—not, as the Americans wished, to recognize it as a condition for treaty making, for he believed such a position would not wrest the Americans from their reliance on the French. Yet by August 1782, he had conceded the issue in order to move the process forward and to draw the Americans to his side, or at least away from the French.

Read more in The American Revolution: A World War, which is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from The American Revolution: A World War © 2018 by Smithsonian Insititution

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.