Viking Map of North America Identified as 20th-Century Forgery

New technical analysis dates Yale’s Vinland Map to the 1920s or later, not the 1440s as previously suggested

:focal(680x427:681x428)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7e/e2/7ee2059d-7698-46ec-9fac-62cc5e4f49c4/vinland-map.jpg)

It seemed too good to be true. Acquired by Yale University and publicized to great fanfare in 1965, the Vinland Map—supposedly dated to mid-15th century Europe—showed part of the coast of North America, seemingly presenting medieval Scandinavians, not Christopher Columbus, as the true “discoverers” of the New World.

The idea wasn’t exactly new. Two short Icelandic sagas relate the story of Viking expeditions to North America, including the construction of short-lived settlements, attempts at trade and ill-fated battles with Indigenous peoples on the continent’s northeastern coast. Archaeological finds made on Newfoundland in the 1960s support these accounts. But this map suggested something more: namely, that knowledge of Western lands was reasonably common in Scandinavia and central Europe, with Vikings, rather than Columbus and his Iberian backers, acting as the harbingers of the colonial age.

In the modern era, the European discovery of North America became a proxy for conflicts between American Protestants and Catholics, as well as northern Europeans who claimed the pagan Vikings as their ancestors and southern Europeans who touted links to Columbus and the monarchs of Spain. Feted on the front page of the New York Times, the map’s discovery appeared to solidify the idea of a pre-Columbian Norse arrival in the American mindset.

As it turns out, the map was indeed too good to be true. In 1966, just months after it was publicized, scholars pointed out inconsistencies with other medieval sources and raised questions about where the map had supposedly been for the past 500 years. In addition, a study conducted in the early 1970s strongly hinted at problems with the original dating of the map to medieval Europe, though outside researchers challenged that finding with concerns about the small sample of ink that was tested, as well as possible contamination. Debates over the map’s authenticity continued in the succeeding decades, prompting Yale and others to conduct a series of largely inconclusive tests.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/49/79/4979c9ba-8023-460b-8551-91eebc1207fa/vinland_map_hires.jpeg)

Now, an interdisciplinary research project undertaken by archivists, conservators and conservation scientists has proven that the map is fake once and for all. Far removed from the 1440s, the analysis of metals in the map’s ink revealed that the document was actually forged as early as the 1920s.

“There is no reasonable doubt here,” says Raymond Clemens, curator of early books and manuscripts at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which houses the map, in a statement. “This new analysis should put the matter to rest.”

This time around, experts used a technique called X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to examine the ink used across the entirety of the map. Their analysis showed definitively that the ink contained titanium, which only became popular in the 1920s. Scans also revealed a note on the back of the parchment that was intentionally altered to make the document seem more authentic. “It’s powerful evidence that this is a forgery, not an innocent creation by a third party that was co-opted by someone else, although it doesn’t tell us who perpetrated the deception,” says Clemens in the statement.

Medieval texts that mention Vinland, as the Vikings called the region, are an amalgam of both Viking and classical, or ancient Greek and Roman, forms of storytelling. The tales they tell are spectacular: blood feuds among Vikings, magical rituals, battles between First Nations and Vikings, lively mercantile exchanges. In recent years, the stories of Viking voyages to North America have shown up in movies, video games, Japanese manga and anime, and more.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5b/dd/5bdd804a-0edf-48b3-a2a6-933019e27cda/ynews-1-1y4a9409.jpeg)

A similar wave of Viking nostalgia in the early 20th century may have inspired a forger to create the purportedly medieval map. As Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America and an expert on manuscript production, says, “The motivation for manuscript forgeries is generally financial or political. In the case of the Vinland Map, both are quite possible.”

The first record of the map dates to 1957, when a dealer offered it to the British Museum on behalf of Enzo Ferrajoli de Ry, a dealer based in Spain. The British Museum turned the sale down, suspecting the chart was a forgery. Then, in the early 1960s, American dealer Laurence C. Witten III bought the map for $3,500 and offered it to Yale, which declined to purchase it for $300,000. Instead, wealthy alumnus Paul Mellon paid for the map and donated it to the Connecticut university.

The motivation for manuscript forgeries is generally financial or political. In the case of the Vinland Map, both are quite possible.

In hindsight, this protracted chain of events probably should have set off alarm bells. Witten was secretive from the get-go about who he got the map from and how—likely with good reason. Before the find was announced to the world, in November 1964, the New York Times revealed that Ferrajoli de Ry had been convicted of stealing manuscripts; the reporter questioned the legitimacy of Witten’s relationship with the criminal and thus the manuscripts he’d previously sold to Yale.

Witten recounted the saga in 1989, altering some points of the story and admitting that he bought the map directly from Ferrajoli de Ry without supporting provenance. As the dealer reflected, “Why did I not then and there insist on a pedigree? My reply can only be that thirty years ago there was no compelling reason to do so.” He added that post-war Europe was awash with manuscripts sold off by desperate priests to cover debts and rebuild their churches.

Despite all these potential red flags, curators at Yale worked closely with colleagues at the British Museum to determine the map’s authenticity. They dated it to the 1440s based primarily on the handwriting style and the age of the parchment on which it was written.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c8/7a/c87ad61e-1572-4cfc-bbd9-4121f484bfed/kensington-runestone_flom-1910.jpeg)

If the map was created in the 1920s, it would have fit within a larger cultural movement that catered to an eager American audience. The forgery closely followed Swedish immigrant Olof Öhman’s 1898 discovery of a carved runestone in Minnesota. Öhman cited the rock as proof that the Vikings had traveled inland from the coast and, coincidentally, built communities in the same area where 19th-century Swedish and Norwegian immigrants were then settling down. Just as with the Vinland Map, scholars were skeptical almost from the start; still, claims about the Kensington Runestone, as it’s known, have persisted for decades, even in the face of quite clear evidence that the artifact is a fake.

As medieval literature expert Dorothy Kim wrote for Time in 2019, 19th-century nationalists looking to create new political and racial myths turned to Viking history as their source material. American poets composed new Viking epics, and, in 1893, a Norwegian captain sailed a replica Viking ship to the Chicago World’s Fair, winning acclaim both in his home country and among Scandinavian immigrants in the United States.

In northern cities, local groups inspired at least in part by anti-Catholic (and, subsequently, anti-Columbus and anti-Italian) sentiment erected Viking statues. By no coincidence, the announcement of Yale’s acquisition of the Vinland Map just so happened to fall the day before Columbus Day in 1965. At times, the myth of Viking America might seem innocuous enough—but the story has always held the potential for exploitation by those seeking to claim the history of North America for white people.

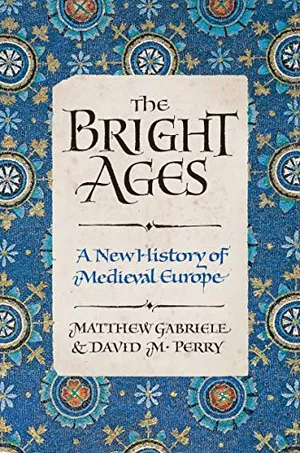

As with almost all versions of nostalgia, false visions of the Vikings grew around a kernel of historical truth. As we explain in our new book, The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe, the people of early medieval Scandinavia (popularly called Vikings today) were constant travelers. Around the turn of the first millennium C.E., they raided the coasts of France and England, then traversed the Volga in Russia, moving south to war and trade with the peoples of the Baghdad-based Abbasid Caliphate.

The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe

A lively and magisterial popular history that refutes common misperceptions of the European Middle Ages, showing the beauty and communion that flourished alongside the dark brutality—a brilliant reflection of humanity itself.

Not long after the map’s “discovery,” archaeologists uncovered an 11th-century Norse settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, confirming Vikings had travel from Iceland to Greenland to the Canadian coast during that period. Now a Unesco World Heritage Site, the settlement is relatively small but was equipped for long-term occupation, boasting the remains of three dwellings, a forge, and workshops likely used for ship repairs and woodworking.

The Vikings’ presence in North America was short-lived, confined mostly to Nova Scotia and (perhaps) some surrounding regions. After island-hopping across the North Atlantic, the Norse appear to have settled down, trading and fighting with Indigenous tribes. Then, according to the two surviving medieval sagas that mention Vinland, these communities succumbed to infighting and disintegrated.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/76/24762ae4-383b-4d30-a896-0f588f3ca2b4/lanse_aux_meadows_national_historic_site.jpg)

In one saga, a woman named Freydís (sister of the famed Leif Eriksson) helps defend the Viking colony by baring her breast and slapping it with a sword to scare off Indigenous rivals. In the other, the same Freydís murders several of her fellow colonists with an axe, causing the settlement to fall apart and the survivors to return to Greenland.

These stories aren’t the ones that inspired the Kensington Runestone or the Vinland Map. Instead, the edges of those tales were worn smooth, washed clean and repurposed in service of early 20th-century politics and culture. Desperate to minimize the role of Spaniards, Italians and Indigenous peoples, some Americans went looking in the past, determined to find themselves. Unsurprisingly, they found what they were looking for—even if it sometimes meant inventing from whole cloth the sources of the story they wanted to tell.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt.png)